Blog: A New World Order in Global Wheat

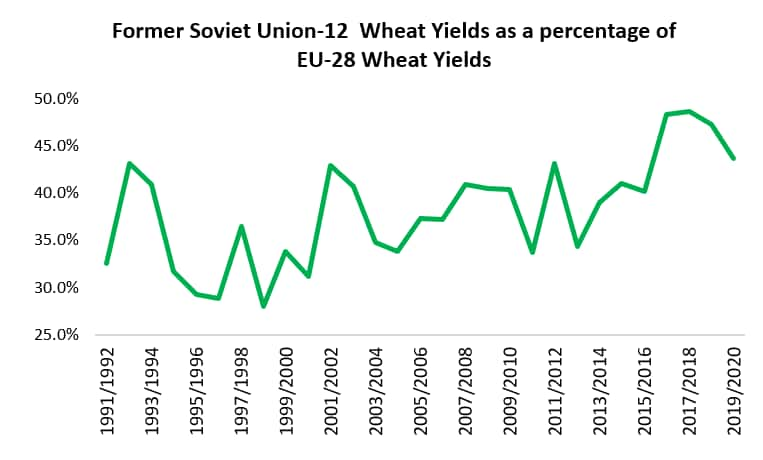

Accelerating structural trends emanating from within the global grains market and exogenous developments are poised to re-shape the wheat market. In world wheat production, wheat yields in the Former Soviet Union (FSU) states have grown by about 60 percent to 2.58 tonnes per hectare since the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. When expressed as a percentage of wheat yields attained in the EU, the data suggests that wheat yields in the FSU region are catching up and expected to converge in about 30 years. Convergence is dependent upon agroclimatic conditions, the pace of adoption of farming techniques from the EU, advanced seed technology from the US and the commercialization of family farms, particularly in countries like Ukraine. US all-wheat yields have grown by about 40 percent from 1991, with offsetting declines in planted wheat area and largely stagnant growth in total wheat production.

Which emerging markets could be key players in the

future?

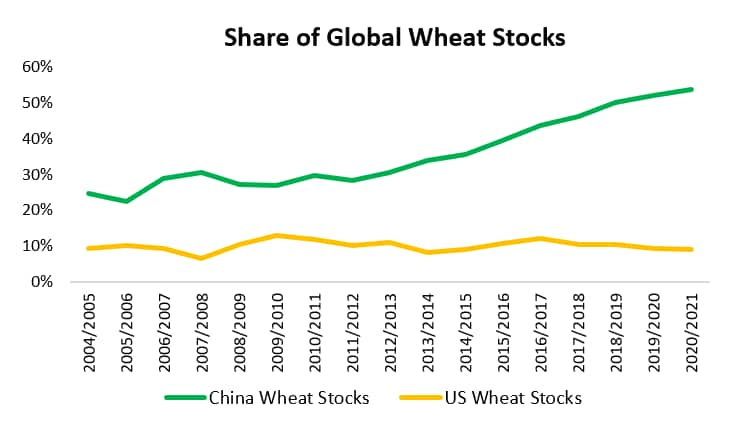

Despite accounting for a meaningful share of world wheat production, India and China are usually not mentioned in the global wheat supply conversation due to their limited roles in the wheat export market. For context, China's wheat yields of 5.36 tonnes per hectare are about 82 percent higher compared with 1991 and closer to absolute levels seen in the EU. India's wheat yields at 3.53 tonnes per hectare are about 55 percent higher compared with 1991 and closer to absolute levels seen in the US, mindful that there are significant differences in protein levels and uses of wheat between these different origins. If India and China continue to improve wheat yield potential at the same historical pace, the risk is that both countries could play a relatively more active role in global wheat trade flows. If the US-China trade agreement results in meaningful purchases of US wheat for storage in 2020 and beyond, China could turn into a meaningful net exporter of wheat in years where there are production shortfalls in other major wheat origins. The risks of climate change, expected to result in warmer winters and less rainfall in the Northern Hemisphere exacerbates supply disruptions.

Which other external factors are influencing global

markets?

Outside of the wheat market, the strength of the US dollar roughly translates to more domestic currency received by wheat farmers for the same dollar-denominated price. The US dollar has been strengthening against the Russian ruble, Ukrainian hryvnia and Indian rupee at least for the past 20 years. The competitive advantage in farm labor accessibility and costs in non-US wheat producers compound on the trend amid a low-price environment in energy and fertilizer costs. Together, these trends highlight the risks that some market participants might be underestimating the extent and speed of the decline of role of the US in the global wheat market.

Finally, shifting consumer preferences in some geographies such as the rise of gluten-free and low-carbohydrate diets are expected to weigh on the trend growth of wheat food use. Abundance of corn relative to wheat could reduce feed wheat demand in the EU in 2020/21, but also provide a glimpse into a future where global ethanol use growth stalls due to persistently low energy prices and some countries hitting the blend-wall, resulting in more competition from corn in feed use.

How will the global wheat market structure

reshape?

In summary, the wheat market in 2040 could look significantly

different from its current form. Global wheat benchmark prices

could be derived from one of the FSU countries. Wheat traders would

pay more attention to China's and India's wheat export prospects.

It would be a world where less wheat-based flour is consumed at

home and perhaps, an environment where wheat will have to find new

applications and demand channels. The risk is that we get there

sooner rather than later.

This article was published by S&P Global Commodity Insights and not by S&P Global Ratings, which is a separately managed division of S&P Global.