Blog: Record US beef production in 2019 - But why is US cattle herd starting to shrink?

There were hints that the expansion phase of this most recent cattle cycle was ending. Into the beginning of 2019, the US cattle herd had grown 7.4 percent (or 6.6 million head) from the six-decade low at the start of 2014. But then the July 1, 2019, inventory report showed fewer total cattle, fewer beef cows and fewer beef heifers being kept for herd replacement. There also was evidence from female cattle harvest volumes (cows and heifers) that had increased in the last couple of years or so at a faster pace than expansion of the breeding herd would have suggested. Then the US Department of Agriculture's Cattle biannual inventory report released January 31 showed the January 1, 2020, US cattle herd was nearly 400,000 head smaller at 99.4 million, down by 0.4 percent. And the US cattle herd is expected to show further modest declines over the next few years.

The mother cow is the "engine" of the cattle herd, beef production

Beef cows produce calves, with some of the calves held for replacement of breeding stock, while the majority of the calves are raised to produce the steaks, roast and hamburgers that end up on consumers plates at home and at restaurants. The value of the offspring provides the majority of revenue to ranchers.

Besides breeding stock, cow-calf operators require access to adequate land, water, forage/feed, capital and labor to produce animals for future beef production. The decision-making process of determining whether to increase or decrease the breeding herd is heavily influenced by the margins of recent years. Due to biological lags and length of growing and finishing phases, it can take two to three years from the decision to increase or decrease the cattle herd to result in increased or decreased beef production.

Rising cattle prices and improving margins will incentivize producers to retain cows longer and hold back more heifers for adding to the breeding herd. Larger cattle supplies and increased beef production eventually will lead to lower cattle prices and reduced margins. Cow-calf operators will respond to a few years of poor to negative margins by increasing the cull rate of their cows and holding back fewer heifers, eventually resulting in a smaller cattle herd and lower beef production, which will lead to a turn to improving prices and margins.

The entire cattle cycle can last a decade or more

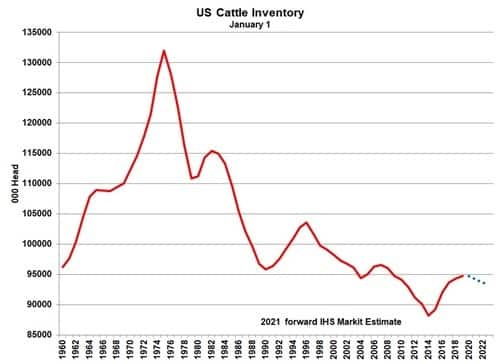

The cattle inventory cycle (the period of expanding the herd inventory from a low point to a peak and then follow with liquidation to another low point) often occurs over a period of 10 to 12 years. Prior to the current cycle, the cattle herd grew from 94.4 million head in 2004 into a peak of 96.6 million head in 2007 before declining to 88.2 million head in 2014. The cycle is often asymmetrical, in that the expansion phase can be longer or shorter than the liquidation phase by a few to several years. Occasional droughts, limiting land carrying capacity and forage production have sometimes extended the liquidation cycle or shortened the expansion phase.

The latest cattle cycle has resulted from record cattle prices and producer margins in the middle of the past decade and the ending of drought conditions in parts of the US that exacerbated the previous liquidation phase. The latest expansion phase has been the most aggressive since the 1970s. After cattle prices declined significantly from the 2014/2015 peaks, feed costs (especially forage) increased. This left producer margins deteriorating in recent years to the point where producers were ending their expansion efforts and some regions were showing the start of declining breeding herd inventory.

Looking further back in time, the largest US cattle herd occurred on January 1, 1973, when there was a total of 132 million head of cattle. This buoyed beef production to record levels of 23.7 billion pounds in 1976. This followed the longest and biggest inventory expansion in history …. but it left the market with a herd liquidation of 16 percent into a 1979 cyclical low of 110.9 million head. Subsequent cycles have shown lower peaks and lower bottoms since the 1980s.

Now, more beef production from fewer animals

Over time, improvements in productivity (genetics, range management, feedstuffs and cattle management) have resulted in more beef being produced from fewer animals. Although the latest cyclical cattle herd peak in 2019 was 37 million head (or 28 percent smaller than the all-time peak in the 1970s), federally inspected beef production reached a new record of 26.8 billion pounds last year. This was more than three billion pounds above the mid-1970s production level.

The US cattle herd could show further modest liquidation over the next few years. But this is seen coming as beef production continues to increase over the next couple of years or so past a cattle cycle peak. This is expected as more female stock are sent to harvest rather than maintained in the herd. US beef production is projected to increase this year once again - marking the fifth year of increases. And beef production then is expected to show a further modest increase in 2021 as well - making both record years.

Find out more about our Beef coverage, as part of our Food Commodities Proteins portfolio.

This article was published by S&P Global Commodity Insights and not by S&P Global Ratings, which is a separately managed division of S&P Global.