Special Report on Food and Ag Commodity Inflation

Highlights

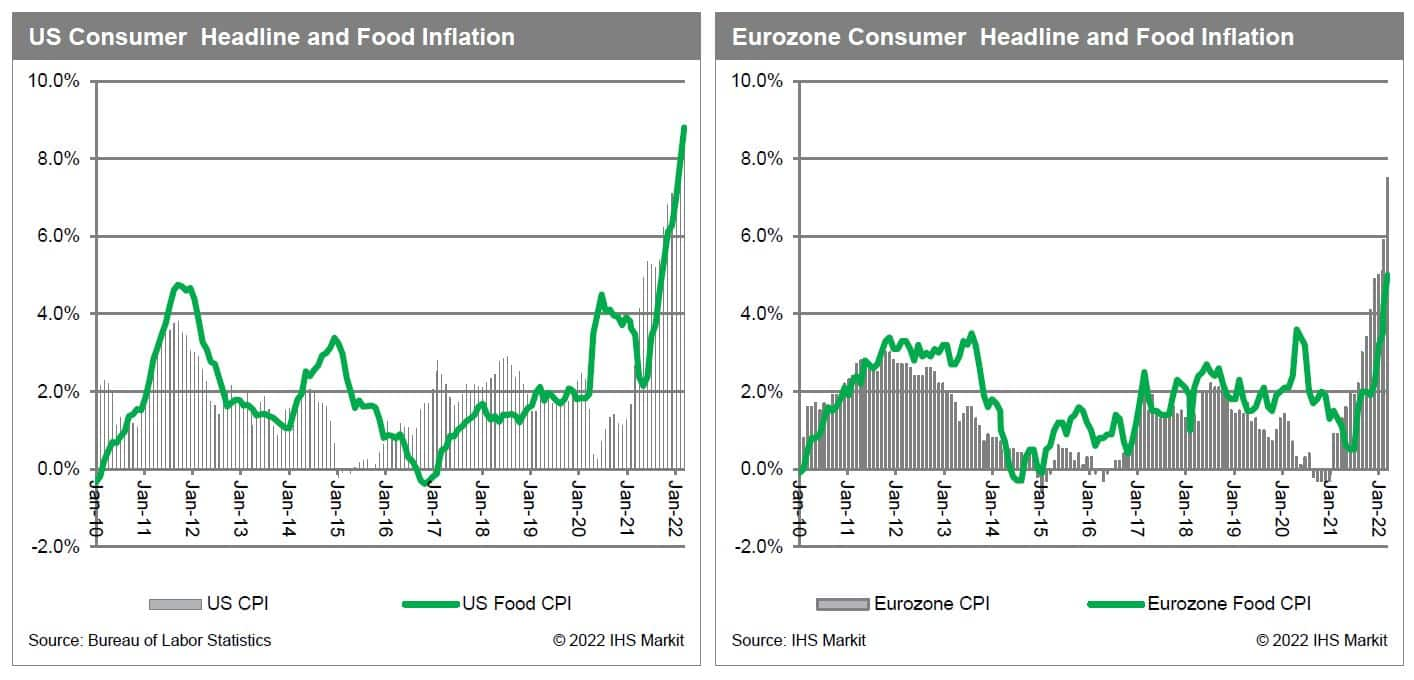

- Inflation, by any measure, has been building momentum dating back to mid-2020. In the US, overall consumer inflation reached 8.5% in March with food inflation at 8.8%. In the Eurozone, overall consumer inflation was 7.0% in March with food inflation at 5.5%.

- While inflation's impact is uneven across the global economy, it is clear it is global and touches virtually every segment, including food and agricultural commodities.

- The causes of the surge in food inflation are numerous and broad. Some are transitory, and some are likely to be lasting.

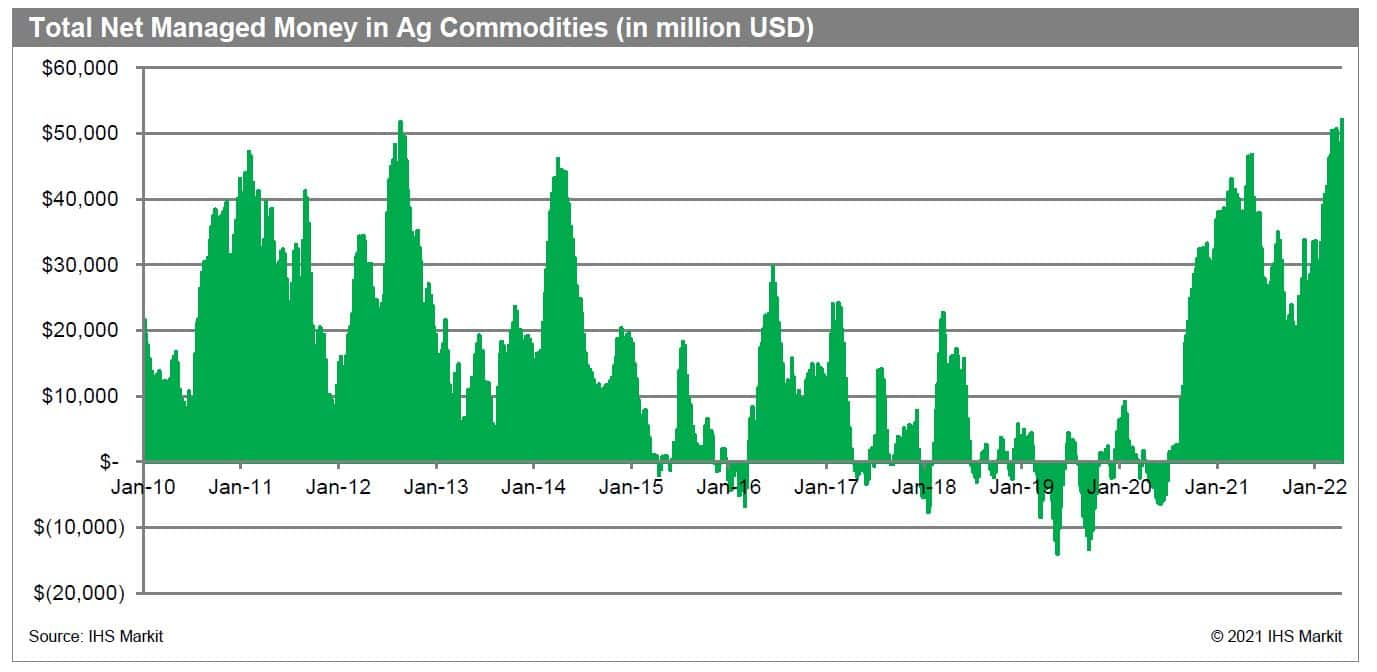

- Investment money flows have followed the inflationary trend, with investment money allocation in ag commodities now sitting at a record $52 billion.

- Economic theory suggests that building inflation expectations makes inflation more challenging to tame. This appears to be taking place in our agricultural commodity markets.

US Consumer Price Inflation is Surging

US Consumer Price Index (CPI), the broadest measure of inflation

at the consumer level, reached 8.5% in March, the highest level

since 1981. This stands in stark contrast to the inflationary

environment that existed less than two years ago. In Q2 2020, when

the US was in lockdown, the US CPI average was 0.4%. At that point,

the concern was deflation triggered by measures to mitigate the

spread of the COVID-19 virus. US Food CPI had not mirrored the

overall CPI through 2020 and early 2021. However, in recent months,

they have moved in lockstep with one another. US Food CPI was up

8.8% in March. Some forces are identical to those driving overall

price levels, and some are unique to food and ag commodities.

Nonetheless, consumers now see their buying power eroded faster

than in more than a generation. Rapidly rising overall and food

inflation is not unique to the US. On the other side of the

Atlantic, the story is similar, albeit not so stark. Eurozone March

consumer prices were up 7.5% and food prices up 5.0%. This compares

to negative inflation levels for overall inflation at the end of

2020, and food inflation below 1% in mid-2021.

Food Inflation is not Isolated in the US & Europe

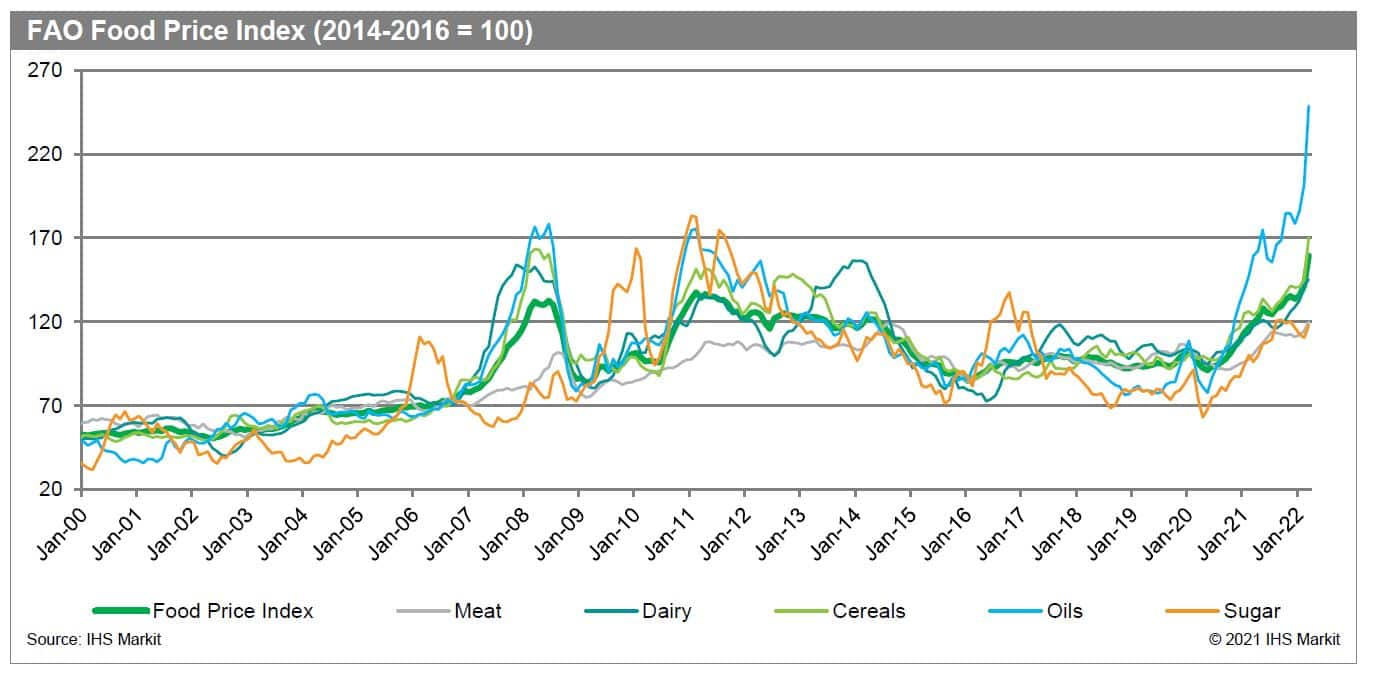

The United Nations' Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO)

produces a widely watched food price index similar to the US CPI.

However, it attempts to measure raw food price changes around the

world. The index rose to record levels in March, rising 12.6% from

February, the largest one-month increase on record dating back to

1991. The index points to a whopping 33.6% year-over-year increase

and up nearly 75% since the 2020-low (May 2020).  The FAO Food Price Index shows

inflation is most acute in cooking oils, up 56% year-over-year and

220% from May 2020. Global meat prices are the most subdued, up 19%

year-over-year and 26% since May 2020.

The FAO Food Price Index shows

inflation is most acute in cooking oils, up 56% year-over-year and

220% from May 2020. Global meat prices are the most subdued, up 19%

year-over-year and 26% since May 2020.

The Causes of Food Inflation Are Varied

The road leading to this food and ag commodity inflation level has been a long and winding one with many unrelated factors since mid-2020. No doubt, the list below is not an exhaustive one. However, we have attempted to include many elements that converged to where we are today.

- Chinese Demand for Feedstuffs Surges: In early 2020, China signed the Phase One trade deal with the US. This coincided with their getting the epidemic of African Swine Fever (ASF) under control. ASF had devastated their hog herd for two years, reducing animal numbers by 1/3 and reducing feed demand. With ASF under control, China's demand for soybeans, corn, sorghum, wheat, and other feed grains soared.

- Decarbonization of Motor Fuels: Converting agricultural commodities into motor fuels is not new. It has been going on in scale for more than a decade. However, a new wave of initiatives and policies have been put in place to reduce the carbon footprint/greenhouses gases. Additionally, a new technology that allows for increased blend levels of vegetable oils and animal fat-derived diesel into conventional diesel fuel caused a surge in demand for oils, fats, and oilseeds.

- Production Issues: Production issues are nothing new. It is an unusual year without some significant producers experiencing production losses due to adverse weather. However, over the past two years, several production issues have led to higher prices. These issues include: 2020 US planted area being low due to depressed prices amid COVID; palm oil seeing production shortfalls due to poor weather; COVID-related labor shortages hindering processing; a drought in Brazil that impacted corn and soybean production; and rising feed costs have led to reductions in animal proteins production.

- Processing and Logistics Issues: The issues across the supply chain of many industries are well-documented. The food industry is no different. Transportation issues around the globe have increased freight rates, snarled ports, and caused shortages. Labor shortages have caused intermittent shortages of meats and produce around the world.

- Policy Decisions: Accommodative monetary policies that kept interest rates near zero until recently, along with fiscal policy aimed at easing the burden of the pandemic, have converged into "the law of unintended consequences." Labor shortages are now chronic at the same time as there is ample money chasing a scarce number of goods.

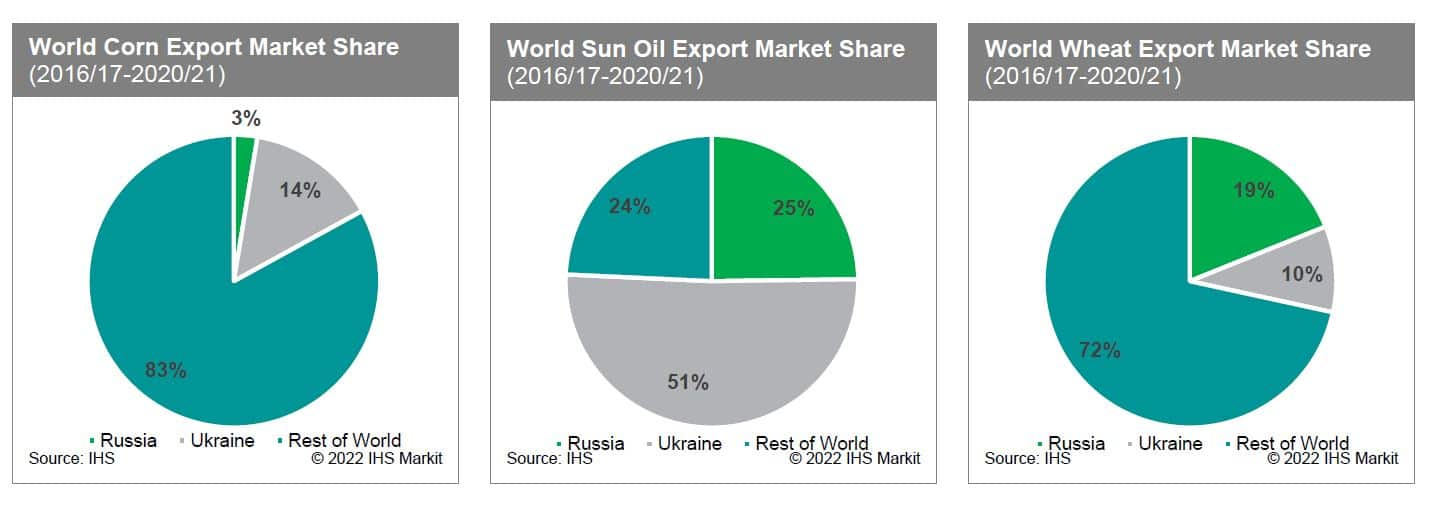

- Russian/Ukrainian War: The Russian invasion of Ukraine is the most recent event that has exacerbated food inflation. Both of these countries are significant exporters of grains and vegetable oils. The war is disrupting the export flows out of each of these countries. In the case of Ukraine, the war has seriously hindered their ability to export. In the case of Russia, sanctions have reduced the willing buyers for their commodities. This has caused widespread disruption in wheat, corn, and vegetable oil markets.

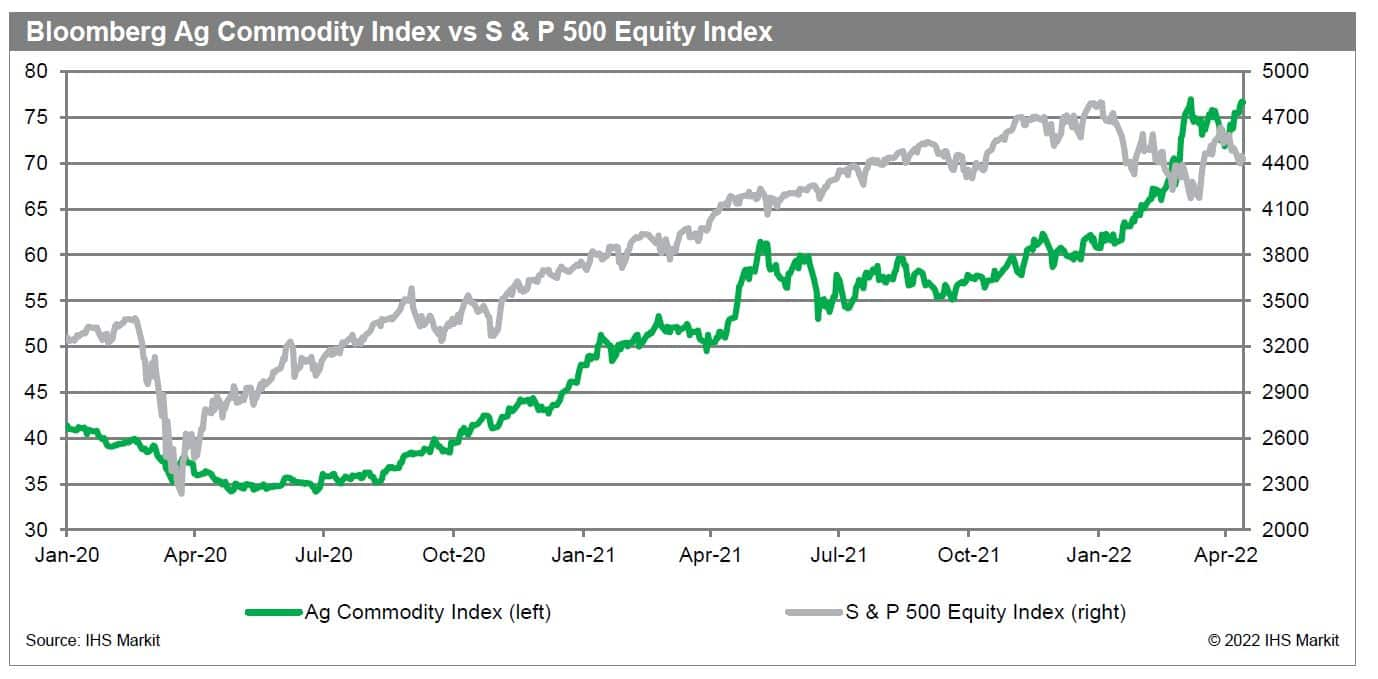

Investment Money has Flowed to Commodities

Exchange-traded ag commodities have outperformed equities. Since

January 2020, the Bloomberg Ag Commodity Index has gained 85%,

while the S & P 500 Index has gained 36%. In the near term, the

contrast is even starker; ag commodities have gained 46%, while

equities have gained only 7% in the past year.  This has caught the attention

of money managers, causing them to increase their asset allocation

to commodities, including ag commodities. This week's total asset

allocation by Managed Money was at a record $52 billion, as defined

by the US regulator of commodity markets, the CFTC.

This has caught the attention

of money managers, causing them to increase their asset allocation

to commodities, including ag commodities. This week's total asset

allocation by Managed Money was at a record $52 billion, as defined

by the US regulator of commodity markets, the CFTC.  This $52 billion net long

position compares to a net short position of $6 billion in mid-2020

and net short $13 billion in late-2019. While the inflow of

investment money into ag commodities is not in itself pushing

prices higher, it is a contributing factor. It also indicates

inflation expectations from pension funds and money managers.

Inflation is a particular fear of pension funds that take in a

fixed amount of money but will owe future outflows to pensioners

indexed to inflation. If inflation goes higher, their future

obligations increase. Few asset classes perform as well as

commodities in an inflationary environment. The willingness for

increased amounts of money to be placed in commodities is a good

indicator of increased inflation expectations.

This $52 billion net long

position compares to a net short position of $6 billion in mid-2020

and net short $13 billion in late-2019. While the inflow of

investment money into ag commodities is not in itself pushing

prices higher, it is a contributing factor. It also indicates

inflation expectations from pension funds and money managers.

Inflation is a particular fear of pension funds that take in a

fixed amount of money but will owe future outflows to pensioners

indexed to inflation. If inflation goes higher, their future

obligations increase. Few asset classes perform as well as

commodities in an inflationary environment. The willingness for

increased amounts of money to be placed in commodities is a good

indicator of increased inflation expectations.

Inflation Expectations Can Become Self-Fulfilling

Our collective expectations play a role in many aspects of the economy, but there are few places where that is more true than inflation. Growing inflation expectations can drive behavior, including reducing savings and increasing spending. As one's expectations adjust higher, behavior often changes in a way that stokes inflation. Buying one's bread today and hoarding it in anticipation that prices will trend even higher in the future is just such an example. It increases the demand for bread and wheat, not because of physical need but because the demand for storing and freezing bread has risen. Inflation can be much harder to slow as expectations are adapted to increasing inflation. Clearly, the size of the managed money position indicates an expectation of increasing ag commodity inflation is becoming entrenched. This has and will likely support prices until expectations are adapted lower.

This article was published by S&P Global Commodity Insights and not by S&P Global Ratings, which is a separately managed division of S&P Global.