Is the Americas offshore wind industry the next big market for Offshore Supply Vessels?

From the mature US Gulf of Mexico market to the fast-growing Guyana and Suriname, recent months have marked an inflection point for the Americas OSV (Offshore Supply Vessels) industry. Both the utilization rates and day rates have reached levels not seen in years since the last supercycle.

The Americas region will continue to flourish, not only by increased oil and gas activity, but also by local governments looking to start investing in, or at least evaluating to develop the offshore wind sector development in their countries. Interest in offshore wind is increasing rapidly in Latin America, particularly in Brazil, where more than 20 companies have applied for environmental licenses for a combined capacity of nearly 176 GW. In Colombia, the country's Minister of Mines and Energy has stated that the first auction for offshore wind capacity will be held in August of this year, with an area large enough to host 4-6 wind projects on offer in the waters off Atlantico department. Some 11 projects with over 5 GW of capacity have so far been submitted to the Ministry. No construction activity is foreseen in the immediate future, with the early phase projects likely to be built leading up to 2030. As for Mexico - the other key Latin American market for OSVs - the situation is different. Despite interest in developing the offshore sector, it will take even more time. Not only there is a lack of infrastructure to distribute energy from offshore wind sources, but it seems to be that the Mexican government has other priorities when it comes to adding new energy sources including solar and onshore wind. However, the potential in the short and mid-term could be in a different direction, not towards building Offshore Wind Farms (OWFs), but into using their offshore engineering know-how, expertise, and infrastructure to build the turbines and jackets. If this activity evolves, it could generate demand for OSVs that could facilitate the transportation of materials and finished pieces for the offshore wind sector. There are already yards used to working in offshore oil and gas in Puerto de Tampico, that are converting into wind turbine jacket construction sites. Benefiting from the low wages and exchange rate in Mexico, if they successfully develop a Fordist serial production line, they may become suppliers to the US market. The US is where there are expectations for faster development. Over the last two years, the US government has set its goal of deploying 30 GW of offshore wind by 2030. With some projects already being executed, the potential for upcoming demand for OSVs is strong.

As for OSVs themselves, the development of floating wind farms seems to offer great potential for generating activity for AHTS (Anchor Handling Towing Supply vessels) and for large DP2 PSVs (Platform Supply Vessels). AHTS vessels have been utilised in different stages of offshore wind projects from pre-installing moorings and anchors to maintenance and decommissioning operations. Although no rigid technical specifications were indicated, a minimum of 15,000 bhp would be expected for an AHTS vessel to allow it to serve the expanding offshore oil and gas and floating wind markets. As for PSVs, over 3,000 dwt would appear to be the preference for offshore wind, including a role in executing geotechnical surveys during the early stages of projects. In general, support charters for OSVs are anticipated to be on a term basis and vessel specifications would be similar to those required for conventional oil & gas works. Apart from that, OSVs would be utilized in post-construction operations, for example operational and maintenance works, and these are more likely to be spot charter and visit basis hires.

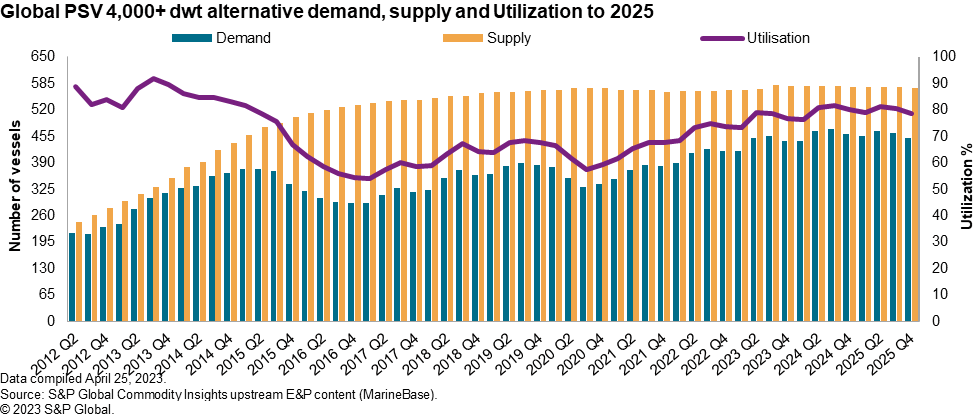

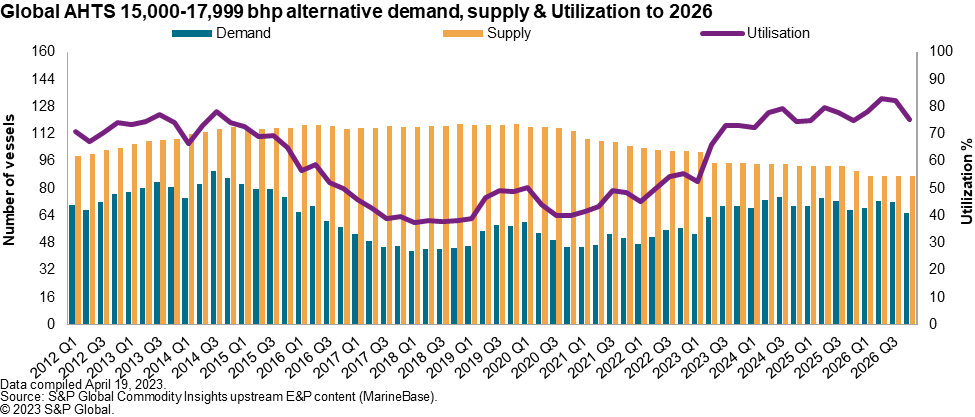

Sources consulted by S&P Global Commodity Insights indicate that the volume of vessels that would be utilised for specific construction works of OWFs per 1 GW of capacity could be as high as 15 vessels for the turbine foundation installation phase and over 10 vessels for structure installation. Phases to install offshore substations and cable arrays could also require over 10 OSVs for each 1 GW of capacity. The real number may vary subject to real-time local factors such as a project's final specifications and timelines, the geography of location, weather, and others. According to American Clean Power, a group of renewable energy companies advocating clean energy, a natural source of the vessels needed to supply the offshore wind sector, are those now involved in similar work in the Gulf of Mexico energy sector, which can be converted for use in the offshore wind market. However, this may not be that simple due to the high levels of utilization for specialized vessels in the region. Currently, the total utilization of AHTS and PSVs, in the Americas is close to 56%, but marketed utilisation (excluding idle and cold-stacked vessels) reaches 89%. For over 15,000 bhp AHTS and over 3,000 dwt PSVs marketed utilisation is tighter, 91% and 87% respectively with the expectation that these figures will increase in the short run due to upcoming projects for oil and gas. Hence, with these levels of utilisation, concerns of possible vessel shortages have started to emerge, once the OWF projects commence and simultaneously those for the oil and gas sector. One solution could be to reactivate laid-up vessels to increase the tonnage in service, however, the number of OSVs that could be reactivated is shrinking. On the other hand, bringing vessels in from other regions is challenging as the offshore wind industry in markets such as Northwest Europe, Asia, Australia, and India will also require more units. It is worth mentioning that globally the demand for both large PSVs and high specification AHTs will increase at least for the following two years as observed in the graph 1, and 2 respectively.

Graph 1. Global PSV 4,000+ dwt alternative demand, supply and Utilization to 2025

Graph 2. Global AHTS 15,000-17,999 bhp alternative demand, supply & Utilization to 2026.

With such limited options to increase the availability of OSVs to cover the short and mid-term demand for offshore wind, the logical answer would be to build new vessels, however, this might not be as simple as its sounds. Significant offshore wind licensing activities are continuing across multiple markets, nonetheless, there are indications that the worldwide macroeconomic environment is starting to place pressure on the viability of prospective wind projects that are being planned to be constructed as late as 2028. Adding to the well-documented issues already identified by developers and investors, such as slow permitting processes and expensive leasing costs, are now the added burdens of historic price increases for global commodities, sharp and sudden increases in interest rates, prolonged supply chain constraints, and inflationary pressures. In addition, there are concerns such as labor costs as these are critical in the financial risk equation, particularly for American OSV companies. There is not enough of an experienced workforce to cover the demand and as a result, labor expenses have increased significantly.

Furthermore, the main concerns among OSV and other services companies are the financial risks and poor profitability, particularly regarding building new vessels to serve the offshore wind sector. It seems that most of the largest OSVs owners are using the lessons learned from the last industry downturns and want to avoid an oversupply of vessels. Some OSV owners largely agree on the opportunities for OSVs that are generated by the emerging offshore wind sector. However, most perceive that it is still in its infancy with limited profits to be had, and thus unattractive.

For the OSV companies, the wind sector could bring significant opportunities for their business to grow but stability and predictability will be necessary to increase their efforts to supply the upcoming demand and to construct new vessels. Most of the OSV owners are adamant that no vessel will be constructed without a long-term contract in place, and day rates should be much higher than the current ones to encourage them to invest in additional units. The key is going to be matching the lifetime of the contract with the lifespan of the asset. As mentioned, the best way they found to respond to the demand from offshore wind is to continue reactivating cold and idle vessels as well as to repurpose OSVs (that are already in the fleet). To serve offshore wind, these vessels need to be made much more efficient and economical with vessels shared among multiple projects, including oil and gas. In other words, both the offshore wind and oil and gas operators must adapt to a very limited supply of OSVs, and thus adjust their budgets and projects.

This article was published by S&P Global Commodity Insights and not by S&P Global Ratings, which is a separately managed division of S&P Global.