Ahead of its first upstream bid round, has Senegal tightened terms too far?

Previous generous terms supported Senegal's upstream development

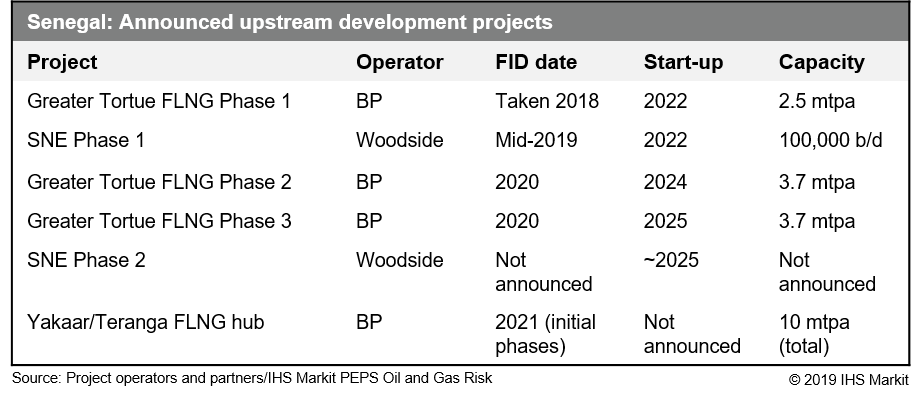

Discoveries in Senegal since 2014 have confirmed the country as a highly attractive deepwater investment destination, with drilling by Cairn Energy and Kosmos Energy—including Senegal's first offshore wells in 20 years—leading to major oil and gas finds. Senegalese discoveries to date account for more than half of the estimated nine billion barrels of recoverable resources in the wider Mauritania, Senegal, Gambia, Guinea-Bissau, and Guinea-Conakry (MSGBC) Basin.

Figure 1: Senegal: Announced upstream development

projects

Senegal's rapid evolution from frontier to de-risked frontier and emerging producer has been facilitated by favourable contractual terms. The 1998 Petroleum Code terms equated to an average government take for offshore production sharing contracts (PSCs) of around 53%. The 1998 terms have underpinned the viability of planned multi-phase oil and gas developments, despite falling oil prices from mid-2014.

Proven below- and above-ground attractiveness has also driven substantial M&A activity, as basin-opening explorers monetise large equity positions and cede operatorships to fast-followers. More deals in existing consortia are likely, with Cairn, Kosmos, and other players likely to further dilute their holdings.

Senegal seeks to capture increased value from next wave of discoveries

Senegal's hydrocarbon production is set to expand rapidly from 2022, increasing state revenues and ensuring gas for domestic use in support of President Macky Sall's "Emerging Senegal" development plan.

However, the president has been criticised for not demanding more from investors, as the country turns to resource wealth to bolster the distribution of benefits and jobs. Political opponents and civil society groups called the 1998 terms outdated and overly generous to foreign investors.

The 2019 code substantially increases government tax take

Political pressure and the desire to maximise the benefits of upstream development led the government to introduce a new Petroleum Code and Local Content Law in February 2019. The new, non-retroactive code shifts Senegal to an exclusively PSC-based regime. Royalty/tax contracts previously offered for onshore areas will no longer be available. Competitive bid rounds will now be prioritised over contract awards via direct negotiation, as the government seeks to avoid further criticism of opacity in its choice of foreign investors and its relationship with them.

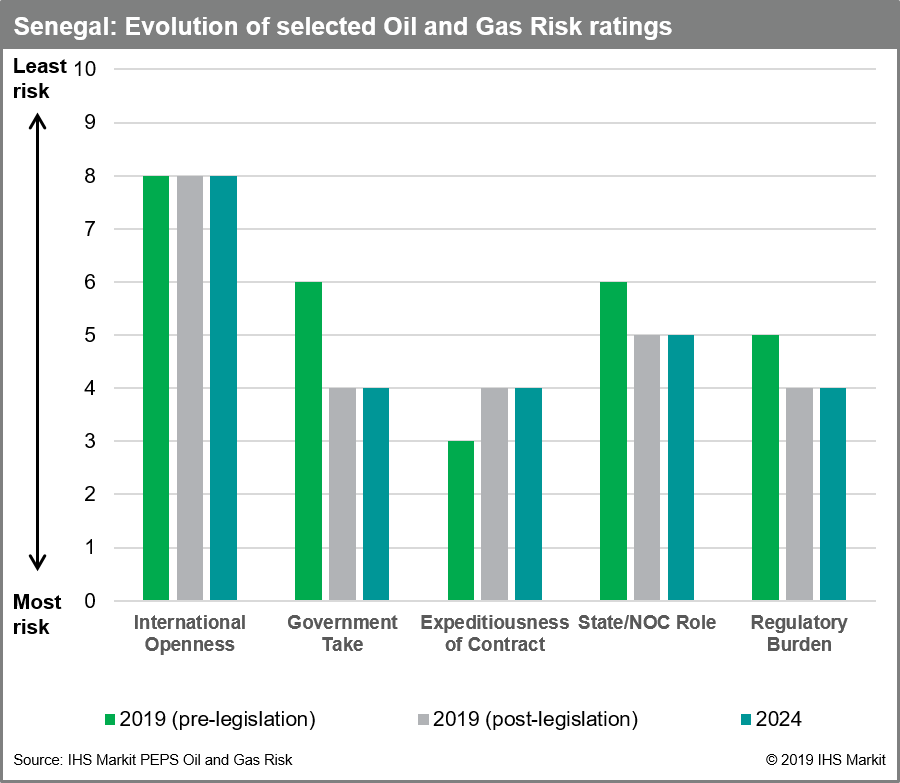

The new code substantially increases tax take—introducing fiscal terms more in line with those of other emerging producers—as the government gambles that the tightened terms will not discourage new investment at a critical point for the sector. IHS Markit fiscal modelling shows that average government take under the 2019 ultra-deepwater PSC terms is approximately 73%, a marked increase on the 53% for offshore contracts under the 1998 terms.

Local content law increases regulatory burden

The new local content law steers clear of establishing an onerous quota system mandating local participation levels, as introduced in other African producers such as Ghana. However, the need to submit a detailed local content plan on an annual basis will moderately increase regulatory burden for international oil companies (IOCs). And due to Senegal's lack of regulatory capacity, it remains unclear how effectively the authorities will be able to monitor compliance with the law. This could leave scope for future government crackdowns on IOC and service company compliance, resulting in fines and/or operational bans.

Figure 2: Senegal: Evolution of selected Oil and Gas Risk

ratings

Senegal's Oil and Gas Risk ratings downgraded due to new legislation

As a result of the legislative changes, Senegal's above-ground attractiveness has changed in some important respects, with IHS Markit PEPS Oil and Gas Risk ratings for Government Take, State/NOC Role and Regulatory Burden all downgraded. However, the country's reliance on foreign capital and technical expertise means that International Openness - the government's openness to foreign investors versus a National Oil Company (NOC) - remains unchanged. Moreover, now that new legislation has been introduced a period of stability is likely to ensue, with no further major changes currently expected to Senegal's key hydrocarbon sector ratings during our five-year forecast period.

Senegal presents IOCs with opportunity for Atlantic Margin Play expansion

Senegal's first upstream licensing round - likely to be launched later in 2019 - will test IOC appetite for its new E&P terms.

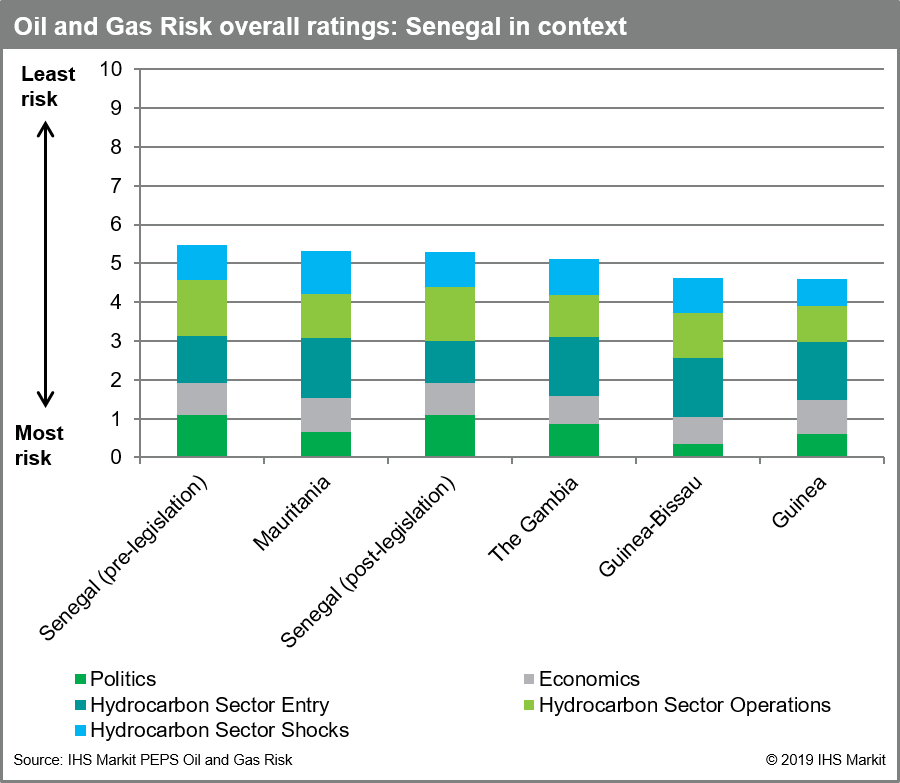

The round could offer established deepwater players already present in Senegal and the broader MSGBC Basin an opportunity to expand their footprints from fast-followers to basin leaders. However, new entrants not seeking an operated position may choose to pursue farm-in opportunities in existing consortia to benefit from Senegal's previously generous terms, avoiding the increased tax take that comes with new licenses.

Figure 3: Oil and Gas Risk overall ratings: Senegal in

context

Despite the erosion of attractiveness resulting from the new legislation, Senegal's relative strength in above- and below-ground factors will help the country remain the leading upstream investment destination in the MSGBC basin, especially given the breadth of acreage on offer. Senegal's acreage provides deepwater investors prime access to the Atlantic Margin play. These factors should also enable the country to set itself apart from regional competitors, such as Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, and the Republic of the Congo, for licensing and IOC capital.

Screen upstream opportunities and above-ground risk with one tool: PEPS

Roderick Bruce is a Principal Research Analyst at IHS Markit.

Posted 16 July 2019

This article was published by S&P Global Commodity Insights and not by S&P Global Ratings, which is a separately managed division of S&P Global.