Are Southeast Asian power systems ready for the rise of renewables?

View a full list of upcoming topics in our Southeast Asia Energy Transition series.

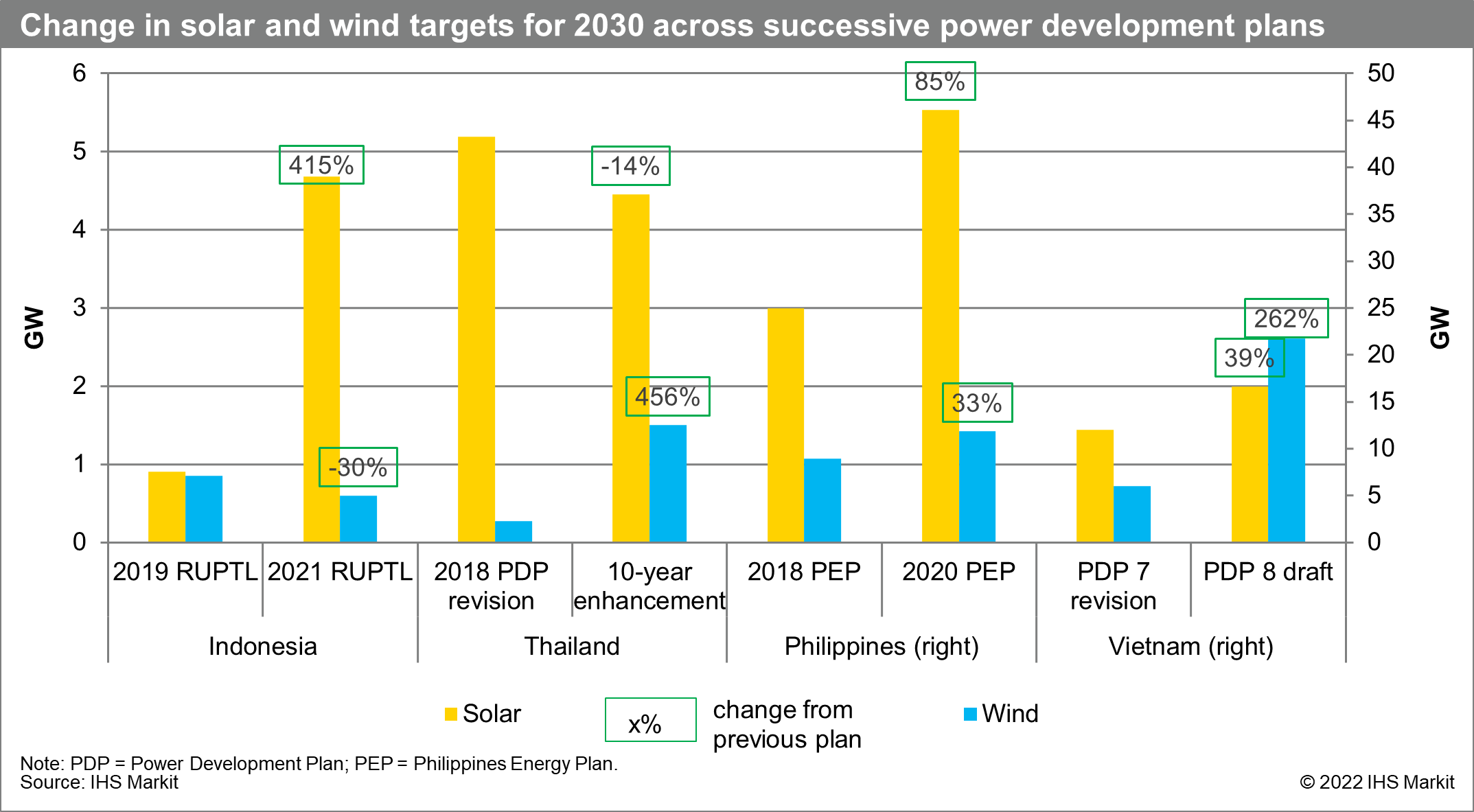

Like most countries in the world, Southeast Asia's economies have made their own nationally determined contributions commitments during the UN climate conferences, most recently updated in 2021 during the Glasgow negotiations. During the Glasgow climate conference in 2021, most Southeast Asian countries announced their new climate targets, with net-zero targets to be achieved between 2050 and 2065. The new targets are more aggressive than before and will require an accelerated energy transition to be achieved. Currently, governments in Southeast Asia have plans to add more than 250 GW of solar and wind capacity over the next two decades, and this will likely be increased further when their power development plans are updated in the coming years.

Grid readiness for more intermittent renewables to be added to the power system

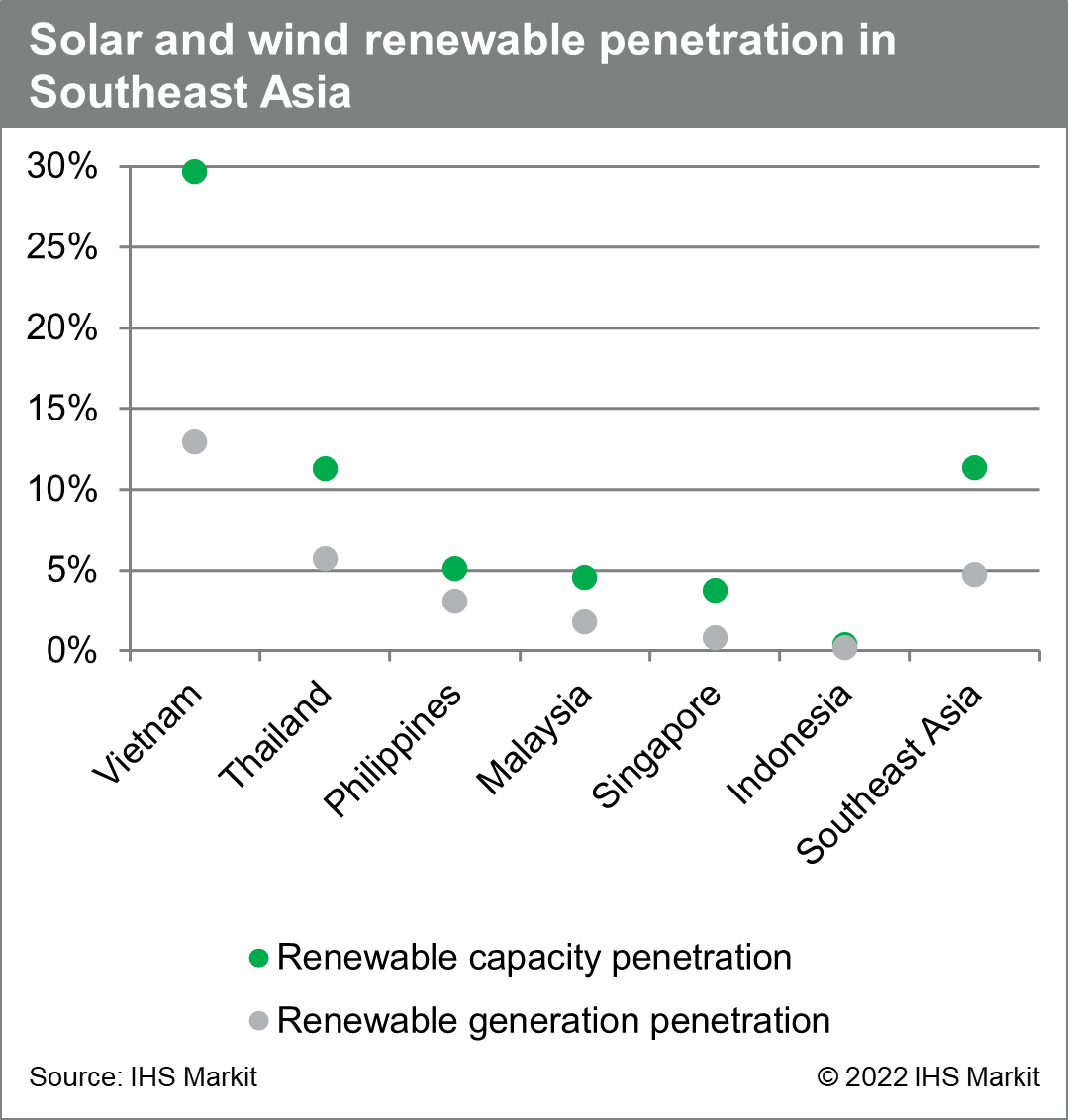

The current solar and wind renewable penetration across Southeast Asia is still relatively low, at 5% and 11% of total generation and installed capacity, respectively, compared with leading countries like Germany, which have already reached levels of 34% of generation and 55% of capacity from solar and wind. This level of renewable penetration is somewhat skewed by the large share of intermittent renewable capacity contributed by Vietnam, which over the past three years has added more than 20 GW of solar and wind capacity. Vietnam's renewable penetration is more than double the region's average, at 13% and 30% for generation and capacity, respectively. Although the level of solar and wind penetration is still relatively low, some countries are already facing challenges in dealing with the intermittency and grid congestion impeding the utilization of solar and wind generation.

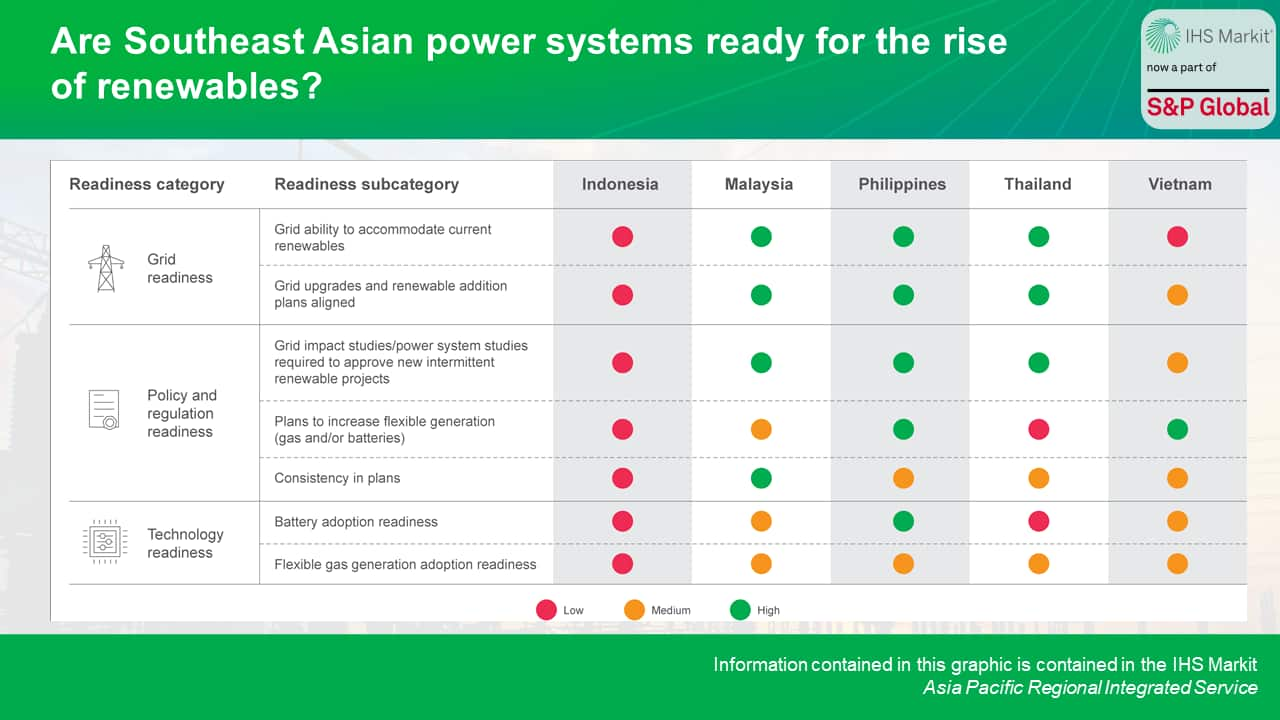

Vietnam and Indonesia will face the toughest challenge to accommodate more renewables. The two countries have the most ambitious renewable target and greatest renewable potential, respectively, and are starting at two extreme ends of the spectrum, with Vietnam having more intermittent renewable capacity than the entire remainder of Southeast Asia and Indonesia having one of the smallest in the region. Despite the differences, they face grid congestion and challenges dealing with the intermittency from renewables, which will hinder future growth of solar and wind capacity.

Grids in Malaysia, the Philippines, and Thailand do not face any challenges to accommodate the operating intermittent renewable capacity thanks to a low renewable penetration and robust requirements before capacity could be developed. Going forward, as solar and wind additions pick up pace (either through increased tender sizes or more aggressive government plans/targets), similar to the rest of the region in their energy transition journey, locations with sufficient grid capacity will dwindle, and similar grid enhancements will be needed.

Countries in Southeast Asia are currently targeting to add close to 50 GW of solar and wind capacity by 2030, and this target is slated to be increased further. Most of the countries have either experienced first-hand the impact to the grid and power system caused by the rise of intermittent renewables or have witnessed the issues faced by their regional neighbors. Each country is facing a different situation in terms of the current state of their grids to handle the existing and planned intermittent renewable additions, but they have all incorporated the lessons from the region into the power development plan, which is to upgrade the grid infrastructure to facilitate the connection for more renewables, in line with their ambitious targets. The plans for renewable additions need to keep pace with the grid upgrades to ensure that the additional renewables can be utilized.

The plans for grid upgrades to support more renewables will come at a high cost. This is because, unlike conventional generators, which can be located closer to the load centers, renewables have a significantly larger land requirement and will need to be developed further away, where land is cheaper. Therefore, as the share of renewables in the generation mix increases, so will the investments in transmission infrastructure. Many of the Southeast Asian countries currently have government-regulated power tariffs, which are set at levels below the cost of supply; therefore, it will definitely be challenging to finance increasingly larger grid investments.

Regulation and policy readiness to facilitate the addition of more renewables

Most of the legacy power development plans for Southeast Asian countries mainly focused on generation capacity additions to serve the strong power demand growth. Capacity expansion planning was weighted on total supply adequacy rather than supply reliability and flexibility. In recent years, more plans are proposed to accommodate the addition of more intermittent renewables across all the Southeast Asian countries' national power development plans. However, beyond enhancements to the transmission and distribution grid, it remains to be seen what the countries will be doing from the regulation and policy perspective to facilitate the development of more flexible generation sources of power demand and supply.

Currently, the main regulatory and policy tool being utilized to ensure that additional intermittent renewable generation does not impact the power system comes from requiring grid impact studies or power system studies before the development approval is given. Both the project developer and the transmission and distribution company are responsible for carrying out these studies together. Such studies have been in place for countries like Malaysia (large-scale solar photovoltaic [PV] tender), the Philippines (Energy Regulatory Commission interconnection agreement), and Thailand (grid connection code) and utilized effectively, as no grid-related curtailment/congestion issues have been reported. Most recently, following the grid issues faced in Vietnam, there is now a clear set of grid-related conditions placed alongside each newly proposed solar and wind project, when they are seeking to be added to the approved national project list.

Long-term power/energy development plans are useful in guiding necessary investments and the corresponding policy and regulatory changes to achieve the target fuel mix. However, in Southeast Asia, many of the long-term plans have a planning horizon of up to 25 years and are being updated frequently. The most frequent updates to power development plans are being done annually, and even the less frequently updated ones are being updated before a quarter of the planning horizon period is over—even though the plans cover an outlook horizon of between 10 and 25 years and typically consist of relatively significant changes. Frequent revisions to the development plans would not be an issue if the changes were not drastic, however, this has not been the case for many countries.

The power development plans across the countries in Southeast Asia appear to still be based mostly on planning based on conventional generation. Although they do mention the need for increased flexibility to allow more intermittent renewables to be added to the generation mix, there is little mention of the addition of flexible generation. This will need to be addressed in future plans to provide more clarity for potential independent power producers to attract investments in such flexible generation sources.

Staying consistent in planning and the creation of renewable energy zones will help coordinate power system planning and allow for faster-pace development of solar and wind capacity. This would be highly beneficial as it will help optimize the limited investment capital available for investments in grid enhancements by concentrating the capital on areas that have better renewable resources and more economically efficient transmission investment outcomes. In addition, this will provide a clear road map for investors and reduce the investment uncertainty on the areas where additional solar and wind capacity and flexible generation can be developed over the planning horizon.

Technology readiness to handle the increasing intermittency in the power system

The recognition of the need for more flexibility in the power system across most power development plans in Southeast Asia bodes well for the accommodation of more intermittent renewable capacity. However, for many of the plans, this is the very first time this has been included and it remains a relatively new concept for much of the region. The supporting mechanisms, such as capacity payment/market, ancillary service market, or frequency regulation service, are not implemented or are still at a very early stage.

Flexible generation is not a newly established technology, but the status quo needs to be changed to enable its development in Southeast Asia. There is currently no clearly defined remuneration mechanism for the delivery of frequency regulation services for batteries, as the only revenue stream is through the sale of electricity, which needs to change. Gas-fired generation is technically capable of playing a role in managing the intermittency, but the current contracting structure, based on a high level of utilization and fuel contracting with high fixed offtake obligations, does not allow for it to play a flexible role. The current gas generation fleet is also not suitable to play a peaking role. Its efficiency and corresponding fuel cost are greatly affected by lower utilization—as much as 300% higher than a baseload plant.

This post is an abstract of a featured topic from the S&P Global Commodity Insights series on energy transition in Southeast Asia, where we deep dive into various aspects of the region's power sector energy transition.

Sign up for updates of strategic reports that will answer some of the thorniest questions on energy transition in the region, drilling deeper into each of the markets we follow.

Learn more about our Asia-Pacific energy research.

This article was published by S&P Global Commodity Insights and not by S&P Global Ratings, which is a separately managed division of S&P Global.