Canadian oil sands running above pre-pandemic highs, but the lingering impacts of COVID-19 and acceleration of energy transition have lowered the growth prospects

By the end of 2020 oil sands output was able to exceed pre-pandemic production highs, and it is expected to continue to grow as operators look to maximize existing operations. Still the industry's long-term growth prospects have declined as market uncertainty continues to delay the timing of new projects and pressures from the energy transition increase.

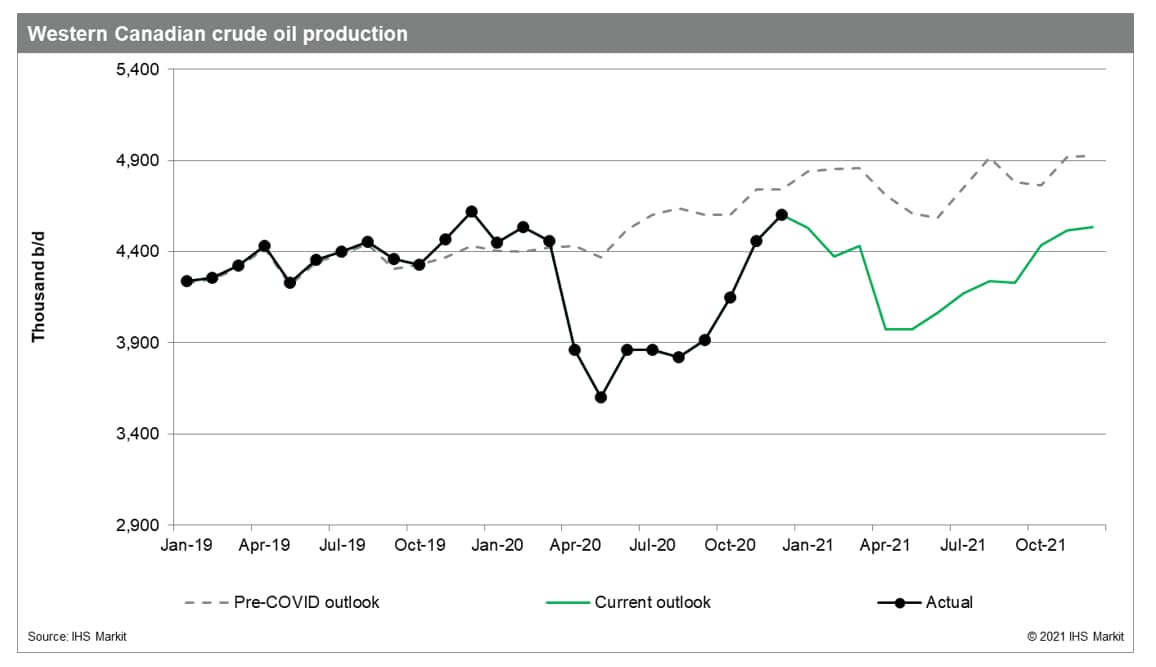

The onset of the global pandemic and the ensuing collapse of oil demand early in 2020 had a profound impact on upstream producers around the world, including in Canada. As demand collapsed through March and April, Canadian upstream producers faced not only falling oil prices, but also dwindling places that they could send their crude oil as North American refineries cut their production runs. The degree of Canadian supply integration with the US refinery complex is unique. Western Canadian production -- which accounts for most of Canada's oil output—is almost entirely reliant on the US refinery system and has limited infrastructure to access markets outside of North America, including floating storage. As a result, during the worst of the pandemic when US demand remained deeply depressed, Canadian producers faced the potential scenario where there could be physical limitations in their ability to store.

The oil sands have not historically been known for reducing output in the face of adverse market conditions. This is particularly true for thermal operations (such as steam assisted gravity drainage or SAGD projects) where there have been concerns that the reservoirs could be compromised if temperature and pressure were not maintained. In 2020, however the industry moved quickly and took creative steps to reduce output. Upstream operators accelerated, deepened, and extended seasonal maintenance while others throttled output, turned-down operations, and in some cases temporarily shuttered parts of their facilities. By May, Canadian production had fallen over 800,000 b/d from January 2020 levels or about 20%. This marked the single largest contraction in Canadian upstream history. To put this into perspective, the scale of the production cut was roughly equivalent to turning off the entire output of Azerbaijan or Colombia--the 20 and 21st largest oil producers globally.

As the first wave of the pandemic subsided and demand (and oil prices) began to show some signs of recovery around mid-2020, Canadian oil sands operations began to recover. The pace and scale of the production recovery was surprising to many. By the end of 2020, Canadian oil sands output was greater than pre-pandemic levels at the start of the year. The recovery of oil sands output benefited not only from their unique production characteristics that feature large facility style operations with little to no production declines, but also some underutilized capacity. Prior to the pandemic oil sands output was already under a mandatory curtailment ordered by the Government of Alberta, which sought to limit production to manage around limitations in western Canadian pipeline export capacity. These measures were removed towards the end of 2020.

Figure 1: Western Canadian crude oil production

Despite the rapid recovery, slower growth in the Canadian oil sands is taking shape. For several years IHS Markit has been expecting a deceleration in oil sands growth.1 But a continuous stream of shocks—most recently and notably the pipeline bottleneck crisis that emerged in 2018 and caused western Canadian oil prices to collapse relative to global benchmark crudes (which in turn led to the imposition of mandatory production curtailment by the government of Alberta), followed by the pandemic in 2020—delayed the ramp-up of existing production capacity and deferred the advancement of new projects. Given the long-lead time associated with oil sands projects, these delays reduced the number of projects and the amount of growth that could be expected by a fixed point in time. At the same time the Canadian oil sands has become more consolidated amongst fewer companies, diminishing the industry's capacity to execute on the same number of projects.

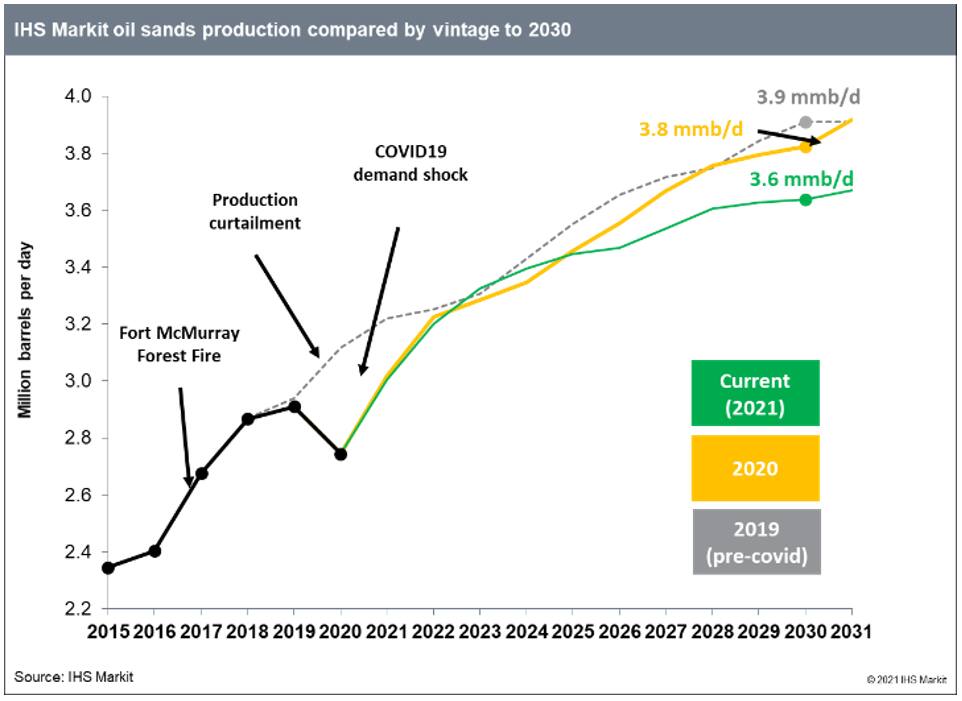

The global oil demand shock of 2020 will have a lasting impact on the future of the Canadian oil sands. Although western Canadian oil prices have rebounded, even exceeding pre-pandemic levels early in 2020, producers are prioritizing rebuilding their balance sheets, paying down debt, and returning cash to shareholders. These actions will further delay a rise in upstream spending in the oil sands and in turn reduce the long-term growth expectation.

Meanwhile a rise in societal pressures to accelerate the energy transition is also weighing on the long-term growth potential for the Canadian oil sands. Investors have already begun to discount future reserves and future production potential, which has always been a distinguishing feature of investing in new oil sands developments. In addition, although the industry has driven down the price at which new thermal projects can breakeven into a similar range to average US shale, the longer lead times and the larger upfront out-of-pocket expense required to bring new oil sands projects online are likely to contribute to a view that oil sands projects are more risky than shorter cycle shale (particularly in an energy transition world where the future of global oil demand is increasingly in question). While the economics of existing operations will continue to prove attractive and resilient, the uncertainty over future demand and longer lead time of oil sands projects is lowering our long-term outlook.2

Figure 2: IHS Markit oil sands production compared by vintage to 2030

IHS Markit still expects growth in the Canadian oil sands, but our outlook has fallen to the lowest point in the past half-decade of forecasts. Still this portends substantial growth. By 2030 annual average oil sands production could exceed 3.6 MMb/d--growth of nearly 900,000 million b/d compared to 2020. Compared to 2021, which may be a better point of comparison, it would represent a rise of nearly 650,000 b/d.

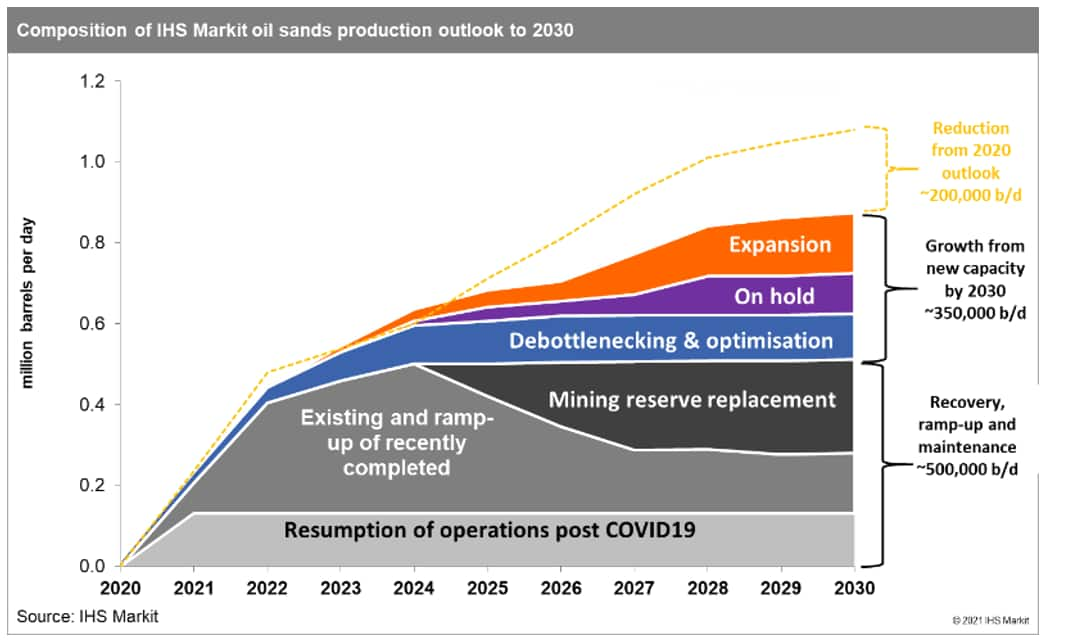

Growth in the Canadian oil sands is supported by both its low decline rate, and the ability of the industry to leverage existing assets. The flat, no decline aspect of oil sands assets provides a stable platform where growth can be more readily achieved in the medium to long-term. This profile contrasts with conventional and unconventional oil production where growth must occur at a rate that exceeds production declines. Meanwhile the oil sands' existing installed capacity, which we estimate exceeded 3.3 million b/d in 2020, provides a large base from which growth can be leveraged.

Figure 3: Composition of IHS Markit oil sands production outlook to 2030

Although our outlook is diminished, it is also increasingly resilient, with less reliance on longer lead time, more capital-intensive new projects. For example, over four fifths of the growth in IHS Markit outlook is expected to come from the ramp-up, optimization and completion of projects where some capital has already been invested. Three-fifths alone is expected to come simply from the ramp-up of existing operations.

To be certain this is a forecast based in today's environment and there are uncertainties. Indeed, additional price shocks and/or greater shifts in societal pressure associated with the energy transition could put further downward pressure on the growth prospects for the Canadian oil sands. However, there are simply fewer large-scale developments remaining in the outlook that could be removed. The outlook for the Canadian oil sands is increasingly about half-cycle economics, or the cost to maintain existing operations (as opposed to new more capital-intensive long lead time developments).

There is also upside potential for the Canadian oil sands principally from a greater degree of project debottlenecking and optimizations than currently anticipated. Debottlenecking and optimization projects have significant advantages such as much shorter development cycles, more modest capital requirements, and can often lower operating cost while increasing output. They are, from a forecasting perspective, also more difficult to anticipate because they tend to emerge organically from operational learning. Some potential optimizations being developed, such as the deployment of solvents that can reduce the steam intensity of thermal operations could prove quite attractive, supporting higher levels of output with little to negligible change in absolute GHG emissions.

2- IHS Markit, "Four years of change: Oil sands cost and competitiveness in 2018, April 2019, www.ihsmarkit.com/oilsandsdialogue.

Posted 23 June 2021

This article was published by S&P Global Commodity Insights and not by S&P Global Ratings, which is a separately managed division of S&P Global.