China’s energy supply policy for the 2021/22 winter: What does “secure supply at all costs” mean?

After maintaining power supply security during two decades of robust growth, in September 2021, China started to experience a serious power shortage, with two-thirds of provinces employing different degrees of load-shedding measures—and not during the summer or winter peak demand seasons.

This marks an energy crisis for China. Natural gas, as a premium and relatively scarce fuel with inadequate storage capacity to provide peak winter supply, frequently experiences supply curtailment to nonresidential sectors during winter seasons. However, as natural gas only accounts for 8% of China's primary energy mix and 4% of the power capacity mix, power rationing has a much more profound repercussion on the market operation and economic activities.

In an emergency meeting at the end of September, Chinese Vice Premier Han Zheng, who oversees the energy sector and industrial production, ordered state-owned energy companies to "secure energy supply at all costs." In a meeting with foreign diplomats, Premier Li Keqiang also reportedly reaffirmed China's efforts to maintain economic growth and supply chain stability.

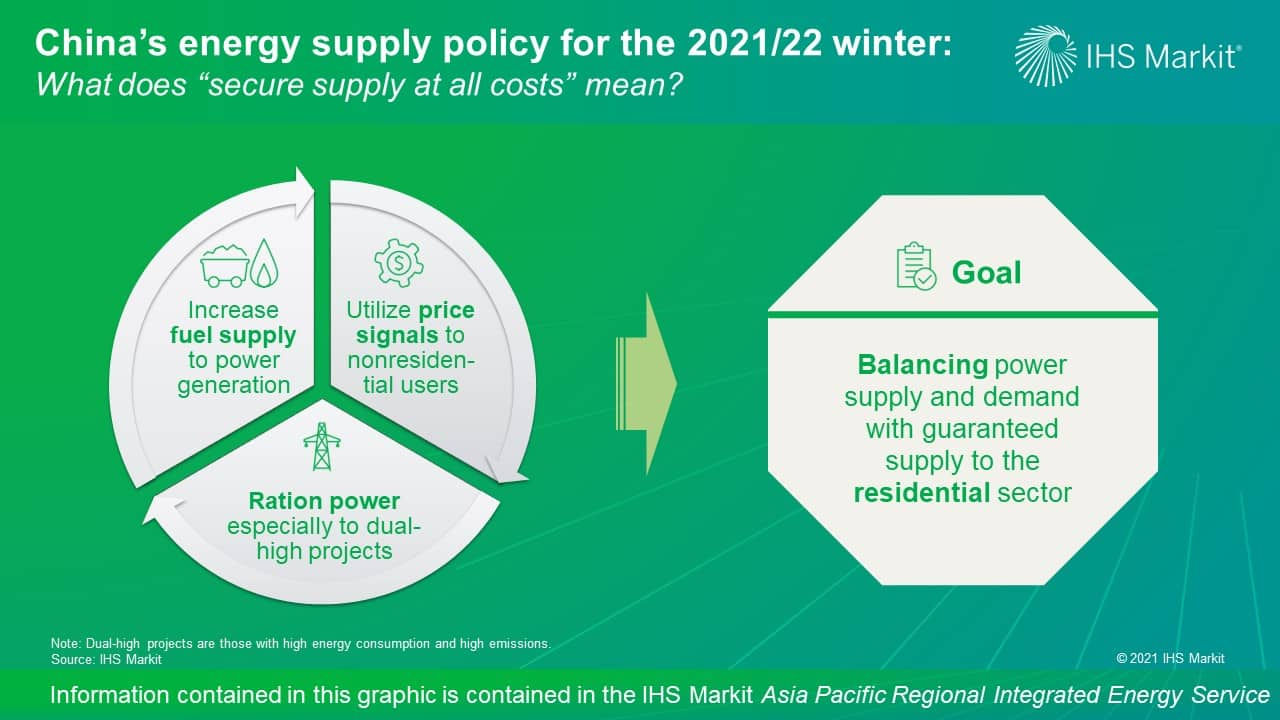

"Securing supply at all costs," however, may not mean literarily that. On 29 September 2021, China's National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) issued a detailed response to reporters' questions on the plan to secure energy supply this winter and next spring. On 8 October 2021, Premier Li Keqiang led an executive meeting at the State Council to discuss short-term energy supply, confirming the key points in the NDRC's report.

Most of the tools that the NDRC listed to secure power supply are measures to increase fuel supply, particularly from domestic sources. Coal, being the largest share of fuel for power generation, was discussed before natural gas. Price signals and cost passthrough are also an option, given that thermal power profitability or the lack thereof in the current spot price environment was an important factor leading to the current power generation shortage. Indeed, on 11 October 2021, the NDRC followed up with a specific policy to allow coal-fired power generation prices to deviate within 20% of the current benchmarks, up from the previously allowed 15% lower band and 10% higher band. However, the updated price range will help improve coal-fired power's financial performance but is still not enough to bring power plants back to profitability, as coal prices have tripled in the past year.

More importantly, even with the measures listed above, the NDRC still indicated that power rationing will remain the tool of last resort to balance power supply and demand with guaranteed supply to the residential sector in the coming winter season. Power rationing will apply first and foremost to dual-high projects—projects with high energy consumption and high emissions, then to other industrial power users.

The multi-pronged approach to deal with the energy crisis is a common practice in China. Consistent with the general prevailing supply security policies, domestic production—whether for coal or natural gas—will serve as the backbone of the supply increase to support thermal power generation. The coal-fired power tariff adjustment will help but does not fundamentally solve the profitability problem of thermal power plants or change the coal-versus-gas comparison in generation profit in the current spot price environment. Power rationing remains a distinct risk this coming winter. In addition, it also helps with the fulfilment of the "dual-control" targets of energy consumption and energy intensity. As a result, the impact of the current policy direction to alleviate the power shortage issue on spot purchases for coal and gas from the global market is limited.

Learn more about our Asia Pacific energy research and insight.

This article was published by S&P Global Commodity Insights and not by S&P Global Ratings, which is a separately managed division of S&P Global.