India’s bold announcements at the Glasgow COP leave too much to the imagination

In what is by far the most ambitious set of climate action targets set by India, a clear action plan is missing. IHS Markit's energy and climate scenarios for India can help decode the unknowns.

Energy security[1] universal and affordable energy access, and environmental sustainability, constitutes the trilemma of objectives that Indian energy and climate policymaking seeks to address. This involves harnessing the synergies and negotiating the trade-offs in satisficing these objectives. Between 2010-20 India's emissions grew by 50% with coal capacity additions growing at three times the electricity demand growth between 2012-17. India's focus on energy self-sufficiency meant enhanced reliance on domestic coal, leading to a net surplus of wholesale electricity availability at an all- India level, though distribution-side challenges remain. Similarly, India is committed to expanding clean cooking choices across rural India where the majority households still use highly polluting non-commercial biomass: notwithstanding the trade-offs between curbing of highly damaging effect of indoor air pollution and additional greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by switching to non-polluting LPG.

From energy-sufficiency perspective, India's energy policy focus has transitioned to efficient management of energy demand and clean energy penetration in the latter half of the last decade. This shift coincided with India's rather tepid Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) announcement of 33-35% reduction in emissions intensity of GDP by 2030 versus 2005 levels, and 40% non-fossil contribution in total installed capacity at the Twentieth Conference of Parties (COP 21) in 2015. India's internal plans of 100 giga-watt (GW) solar and 175 GW of total renewable installed capacity by 2022, together with large hydro and nuclear expansion meant India would easily over-achieve its 40% non-fossil contribution, even even if it underperforms on its renewable targets. Similarly, despite its coal capacity additions in the last decade, India is set to meet its 1st NDC emission intensity reduction much prior to the 2030 deadline, thanks to a robust GDP growth outlook and autonomous improvements in energy intensity.

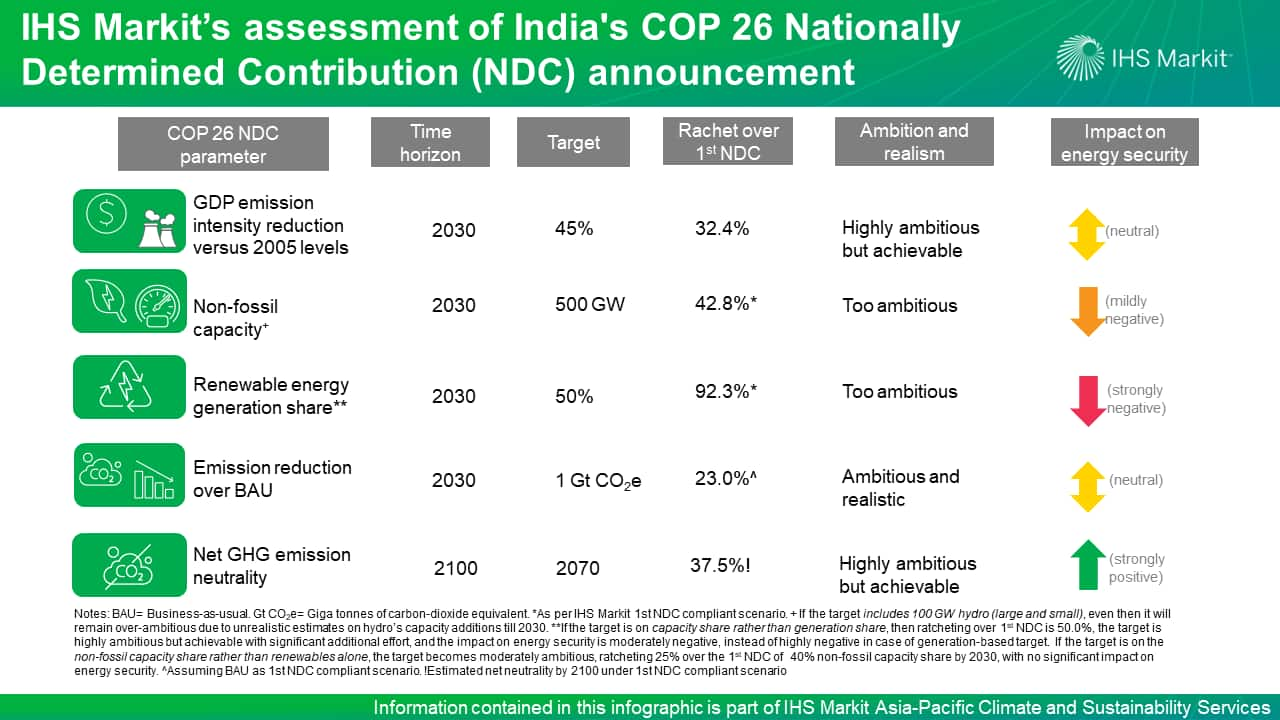

The 2015 Paris Agreement stipulated a forward-looking climate action roadmap for countries, focused on ramping up climate actions for steeper declines in global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions growth trajectory. At the 26th CoP in Glasgow, India's Prime Minister Mr. Narendra Modi announced a five-pronged plan for ratcheting up India's climate ambition as below:

- 45% reduction in emission intensity of GDP by 2030 compared to 2005

- 500 GW non-fossil capacity by 2030

- 50% share of RE in total electricity generation by 2030[2]

- 1 Giga-tonne of carbon dioxide equivalent (GtCO2e) reduction in absolute emissions from business-as-usual (BAU) by 2030

- Net carbon neutrality by 2070.

IHS Markit's assessment of India's future energy and emissions scenarios indicates that some of these targets are achievable with significant additional effort over the current policy scenario, named Inflections (base-case). Inflections is based on harnessing synergies in overlapping aspects of Trilemma objectives, for example, an intensified push towards electrification of demands in hard-to-abate sectors (industry and transport), enhanced energy efficiency, and an organic escalation of renewable penetration to reduce dependence on fuel (particularly, oil imports). However, domestic coal remains the pivotal fuel around which energy transition proceeds, as intensification of household electricity access remains key priority. As India's energy security and energy access goals remain prime concerns, there is no clear roadmap on peaking coal consumption, which constitutes nearly 70% of India's GHG emissions.

The Green Rules scenario, on the other hand, places India at the heart of global coordinated climate action, and the ensuing trade-offs with energy security and access objectives is addressed via complementary strategies.

- India pursues accelerated shift towards hydrogen, particularly green hydrogen with the objective of reaching at least 70% green hydrogen share by 2050.

- It also grows its renewable energy (RE) additions at over twice the pace of Inflections scenario and battery capacity to 245 GW (14% of world capacity) by 2050.

- Gas plays an important role as a transition fuel in power and transport till early 2030s before batteries and hydrogen kick in at scale. This leads to halving of existing coal capacity by 2050.

- On the demand side, accelerated push towards electric vehicles, long-distance travel on hydrogen and gas, freight's modal shift to 100% electrified and green railways, enabling last-mile connectivity, enhancing public transport, and restricting private vehicular ownership and use constitute key strategies to restricting oil import growth to levels in 2015-20 by 2050.

Our scenarios indicate 41-46% reduction in emissions intensity of GDP by 2030, with the post-Covid lockdown GDP growth expected to bounce back to 6.7% compounded annual growth rate in the 2021-30 period. Therefore, the first Indian NDC target is at the upper end of our range and nearer to the Green Rules scenario outcome, indicating strong ambition. However, we estimate a maximum of 353 GW of renewable, 72 GW of hydro and 18 GW of nuclear, totaling 443 GW of non-fossil capacity by 2030, instead of 500 GW as announced. As regards PM Modi's earlier announcement of 450 GW renewable capacity by 2030, our view is that structural deficiencies in the power sector and under construction project pipeline together imply that such a scale of RE cannot be accommodated in this timeframe. The Power Minister's suggestion of including 100 GW of hydro (of all sizes) to achieve 500 GW of renewables by 2030 is still highly ambitious but appears more realistic than 500 GW of solar and wind capacity alone. However, ecological, siting and rehabilitation related challenges in resource-rich regions continue to plague hydropower development in India, due to which realizing 100 GW of hydro by 2030 appears highly unlikely.

Further, it is highly unlikely that coal-based electricity which constitutes nearly three-fourths of total electricity in the country today can be displaced to the extent that renewable-based or even non-fossil electricity reaches 50% or higher share in the mix. Such scale of renewable energy poses reliability and financial challenges for the grid and distribution companies respectively aside from risking stranded renewable assets, given that grid-level storage with renewables is much costlier than conventional sources today. Accordingly, we expect non-fossil energy to cross 50% threshold in the generation mix in the 2030-35 timeframe in the Green Rules scenario, coal-based electricity falling to nearly a third of the mix by 2040 from 55% in 2030. Therefore, we classify the third target as overly ambitious as well.

There is a suggestion that the third target was meant to be denoted as 50% share of renewable energy capacity rather than electricity generation. In such a case, our analysis suggests that India would need at least 390 GW of renewable capacity, which is 37 GW higher than Green Rules scenario outcome for the 2030 horizon (or an additional 4 GW annually for 2021-30). The highest share of renewable capacity achieved is 45% by 2030 in Green rules. Therefore, this target would be characterized as highly ambitious but achievable with significant additional effort. However, if as suggested by the Power Minister, the target is based on non-fossil capacity share then it is only moderately ambitious, as it ratchets 25% over the 1st NDC target of 40% non-fossil capacity share. At the same time, it is incompatible with 500 GW renewables target (irrespective of whether hydropower is included or excluded) since renewables will then constitute at least 60% of installed capacity.

In declaring 1 Gt CO2e reduction from the BAU by 2030, India has adopted a communication approach similar to its South Asian partners like Pakistan and Bangladesh. Since the official BAU trajectories have not been announced, it is difficult to comment on how realistic or ambitious this target is. However, using IHS Markit Inflections scenario, India achieves 407 Million metric tonne (MMt) of CO2e mitigation by 2030, and 2.9 GtCO2e mitigation between 2021 and 2030. Therefore, we can safely assume our Inflections scenario considers much stronger mitigation thrust than government's BAU. For instance, industrial energy intensity (energy per unit output) declines to less than one-third of current levels by 2050 in the Inflections scenario, whereas the Perform, Achieve and Trade (PAT) scheme of the government achieves only about 1.25% average annual decline in the period 2014-20 for selected energy-intensive industries. Therefore, the level of ambition for this target remains indeterminate given the lack of knowledge on official emission trajectories and underlying assumptions.

Until recently, India has been a reticent participant in adopting net GHG neutrality targets. However, at the sidelines of the recent UN General Assembly prior to COP 26, India made a pledge on net neutrality conditional upon its national circumstances. IHS Markit has been of the view that net neutrality by 2050 is highly unlikely for India, given its development context and inequalities in access to basic services, including energy. However, the Green Rules scenario GHG emissions peak in 2030-35 timeframe, in large part due to peaking of coal and oil demand in identical phases. This hinges on technology and policy enabled, yet citizen-centric transformations in power, transport, and industry sectors. To reach this milestone within a decade and a half would be a stupendous achievement which will put India on a sound footing for peaking GHG emissions within the 2065-70 timeframe.

Therefore, a noticeable weakness or ambiguity in India's 2021 NDCs is the lack of any clear announcement on peaking GHG emissions. The Prime Minister's speech at the 26th COP missed laying out any interim targets between 2030 and 2070 which would allow us to assess the realism behind India's peak emissions year estimate. Considering China has declared peaking GHG emissions before 2030 and net zero by 2060, we can guess that Indian calculations are based on similar timeframes with a 10-year lag.

However, unlike battery storage, the other two critical supply-side technologies needed to achieve net-zero, namely green hydrogen and carbon capture and utilization (CCUS), are far behind in terms of maturity. Therefore, any assessment on the trajectory from peak GHG to net zero in Indian case is based on generously optimistic conjectures on the pace of development in hydrogen and CCUS allowing them to compete in the market and reach scale.

A more pertinent and proximate question for India is how it plans to peak its coal consumption given technological barriers, coal's role in energy security and access, and the political economy of coal. This also requires a rapid scaling up of India's green energy manufacturing for which it remains largely reliant on Chinese imports. Without a clear roadmap on coal and oil, which together constitute nearly 70% of India's total primary energy supply today, India's new NDCs remains a wish-list of climate piety.

Learn more about our energy research into India and the rest of the Asia-Pacific region.

Mohd. Sahil Ali is a senior sustainability analyst with the Climate and Sustainability practice, covering cross-cutting issues in energy and climate change for Indian and South Asian markets at IHS Markit.

Posted on 17 November 2021

[1] Energy security implies reliably securing energy supplies for national economic development and strategic imperatives. For India, oil has traditionally constituted the largest item in import spending basket and the Indian energy policy has focused on diversifying away from oil to domestic fuel sources, including clean energy. However, energy security is not simply limited to import reduction: managing oil reserves to absorb the shocks in global oil prices is also a key element in India's energy security strategy.

[2] Some commentators have observed that Mr. Narendra Modi may have meant to convey the target as 50% share of RE in the total capacity mix by 2030 instead of generation mix. Few days after the PM's address, Power Minister R.K. Singh suggested that the 50% target was meant for non-fossil fuel capacity, and that the 500 GW non-fossil target constituted only renewables and large hydro. We analyze all these propositions in this article.

This article was published by S&P Global Commodity Insights and not by S&P Global Ratings, which is a separately managed division of S&P Global.