Key trends shaping upstream above-ground risk in 2021

The expectation of a modest (albeit potentially volatile) recovery for oil and gas markets in 2021 is good news for E&P investors and governments of hydrocarbon-producing states alike, but the outlook is not without serious above-ground risks.

Shifting geopolitical dynamics, climate change mitigation efforts, energy transition pressures, and intensifying political, economic, and social challenges in a number of producing states will drive changes to the above-ground investment environment, creating new risks alongside the potential for new opportunities.

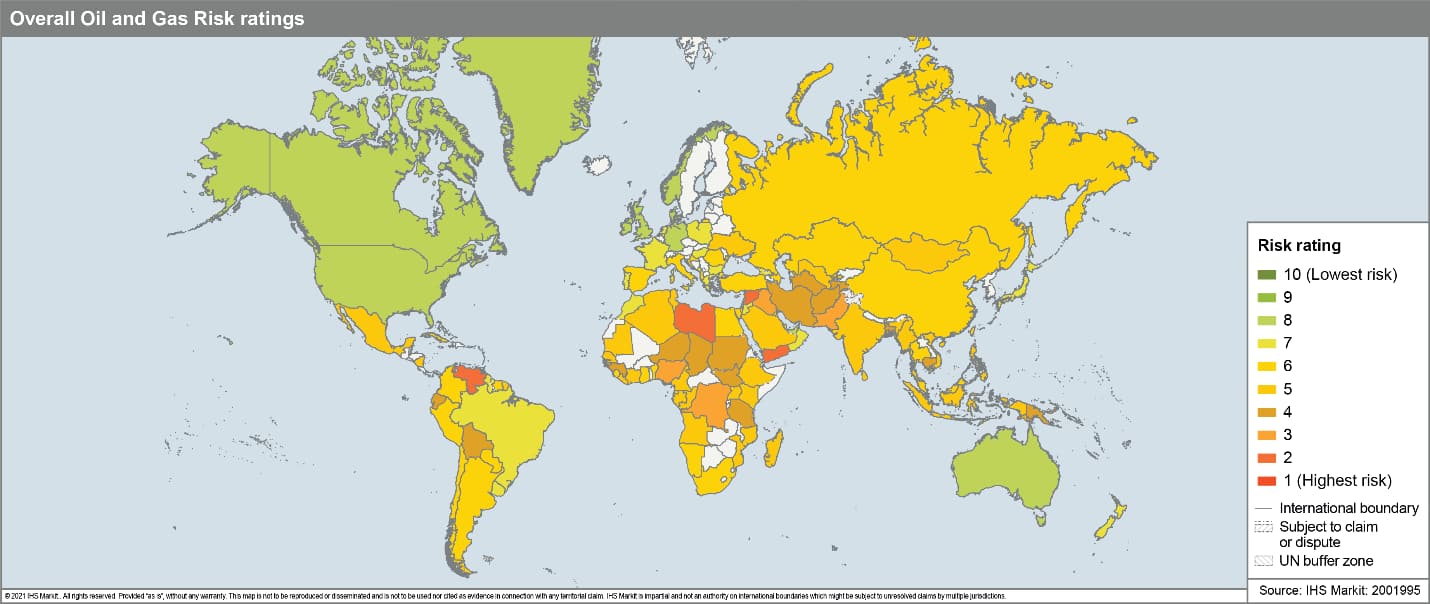

Figure 1: The upstream above-ground risk environment varies dramatically across the 118 countries rated by IHS Markit E&P Terms and Above-ground Risk.

The IHS Markit E&P Terms and Above-ground Risk team has identified eight global trends that will shape the year ahead:

- The installation of a new US administration heralds a return to more traditional foreign policy and reengagement with multilateral institutions. In particular, bilateral relations with China, Russia and Iran are likely to shift, with some becoming less confrontational and others more so. This will have knock-on effects for energy trade and investment flows, with US sanctions a lever of choice that will open or close upstream opportunities for US companies and those exposed to US financial markets.

- The US will adopt a more aggressive climate change mitigation strategy and add to international momentum for more ambitious carbon reduction targets and accounting. These actions - including rejoining the Paris Agreement and likely commitments to net-zero emissions by 2050 and decarbonised power by 2035, as well as a review of all federal policies that impact climate - will put pressure on long-term hydrocarbon demand and raise the cost of doing business in some climes.

- Globally, the translation of lofty climate goals into near-term policy is likely to be bumpy, creating uncertainties in the hydrocarbon demand trajectory and the stability of investment conditions. In cases where producer governments have embraced emissions targets alongside an important E&P industry - e.g., Canada, Norway, China, and the UK - the struggle to balance upstream promotion with carbon cuts may create policy inconsistencies. Much of the debate across all countries will centre around who bears the initial cost of changes to lower carbon futures, be it government, industry, or consumers.

- Portfolio restructuring by international oil companies (IOCs) and major independents will continue to reduce E&P investment in some countries where the upside is deemed as marginal or too carbon-intensive. For some producing countries - e.g., Malaysia, Indonesia, Equatorial Guinea, and Gabon - this will leave the future of some assets in the hands of smaller companies and/or host country national oil companies (NOCs) that may or may not have the requisite capabilities to monetize the resources. Where no buyers can be found, stranded assets are a growing possibility.

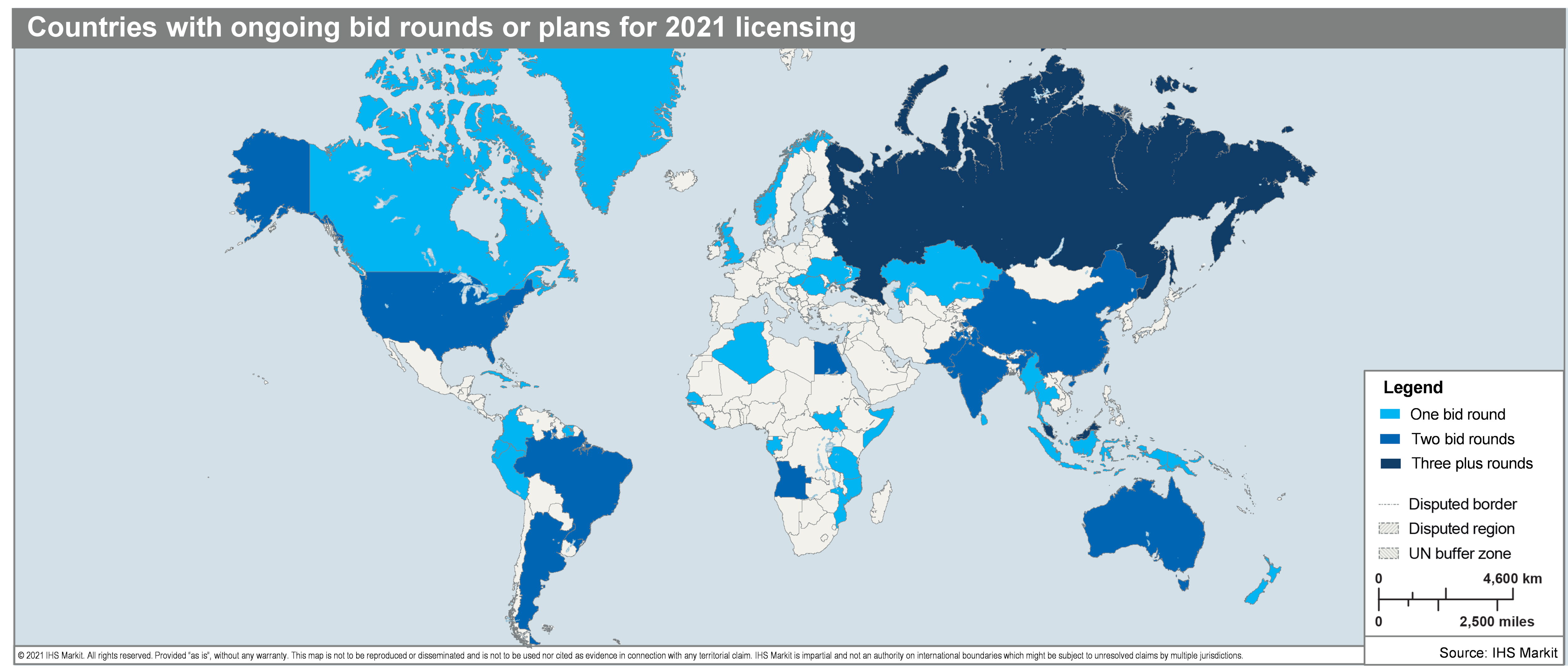

- Changes to E&P terms to boost investment access and attractiveness are likely in some locales, although local content concerns remain a watchpoint for additional costs. In countries where the oil and gas industry is viewed as a central tool to generate revenue and create employment, there will be impetus to boost upstream access (via bid rounds, open-door licensing or direct negotiation), maintain the procedural flexibility adopted to deal with COVID-19 pressures (e.g., online licensing), and, in some cases, consider more structural fiscal and contractual improvements to secure investment from a smaller pool of E&P capital.

Figure 2: Forty-four countries are planning to hold an estimated 59 licensing rounds by end-2021, including bid rounds carried over from 2020 (but excluding open-door licensing opportunities).

- Financial strain will test the stability of some hydrocarbon-dependent states. Despite a rise in oil prices from 2020's lows, many net exporters will remain under significant financial pressure. Those producers unable to make the necessary reforms due to political constraints and maladministration (e.g., Iraq, Nigeria, and Republic of the Congo) risk sparking increased political instability, which could spill over into oil sector administration and operational risks.

- Social protests will make a comeback as the pandemic recedes. Oil and gas assets and infrastructure may once again be targeted as a means for disadvantaged communities to capture central government attention (e.g., Peru, Tunisia, Libya, and Kenya), while environmental protesters will pose an ongoing risk to operations in parts of Europe, Latin America, and North America, albeit with different motivations in play.

- E&P moratoria and other upstream restrictions will continue to spread. Government restrictions on upstream activity have made incremental headway, often as a result of civil society pressures. Until now, the amount of affected acreage has been limited, but with a number of producing governments considering new bans on activity, the proscribed acreage may expand sharply.

These trends will be felt unevenly across the globe, with the accelerated pace of change evident in significant shifts to risk profiles that will prove decisive in determining where scarce investment dollars flow.

Learn more about our petroleum risk solutions.

Mariam Al-Shamma is a director in the Upstream E&P Terms and Above-Ground Risk team at IHS Markit.

David Gates, Ph.D., is a senior consultant for the Upstream E&P Terms and Above-Ground Risk team at IHS Markit.

Posted 28 January 2021

This article was published by S&P Global Commodity Insights and not by S&P Global Ratings, which is a separately managed division of S&P Global.