Middle East Dilemma

The magnitude of the pressure currently on the Middle East

petrochemical industry is one not experienced before. The rapid

decline in oil prices has catalysed a move to unprecedented cost

developments around the world, with European and Asia producers

seeing close to, or even, negative cash costs for producing

ethylene from naphtha. Some of the support for that development is

temporary, as co-product values have not yet had sufficient time to

adjust to the new energy environment but are simply a function of

naphtha prices being so low relative to history. A detailed

discussion on the developments can be found in the special focus

published earlier in April.

Moving from a price taking player to a potential price setter will

not be comfortable for the Middle East, even if only on a

short-term basis and will result in unprecedented margin pressure

for the industry. However, in a new environment, new perspectives

are needed to understand how markets will behave, and ultimately,

who ends up where in respect of market access, volumes and

profitability.

The current environment is expected to be a temporary one, with an

assumed resumption of close to normal economic activity by the

start of 2021. For this to be achieved, a reasonably effective

treatment of readily available vaccine will have to be found, if

not the cessation of travel is set to persist and oil demand

contraction will dwarf the cuts that have been agreed so far. There

is no real clarity on how different economies will be able to

manage in this environment and return to previous levels of

economic activity. So, despite a base case that suggests a recovery

in crude oil demand and a re-balancing of the oil markets over the

next 12 to 18 months, a much more challenging scenario needs to be

considered, one in which the demand for oil peaked in Q4 2019 and

the market will never again reach that same level of demand.

Clearly, for the Middle East economies the future of oil is

critical and will be the focus of governments and major companies

in the region. Cheap oil means recession for the region and the

longer oil remains cheap the bigger the economic and political

challenge. However, it is not just the oil industry that is hurting

but downstream industries are also suffering. The refining industry

is facing a huge overhang of capacity and the petrochemical

industry, which has seen more robust, on a relative basis, demand,

was already shifting into major oversupply. The refining advantage

in the Middle East has been relatively small, if any at all, but

has simply been a mechanism for oil producers to increase cash flow

along with supporting local fuel demand. For petrochemicals, there

has been a stronger rationale for investment, with several products

able to avoid low value fuel usage or even the prospect of flaring.

This has driven the industry to look to upgrade all streams of

ethane in the region through conversion into polyethylene and

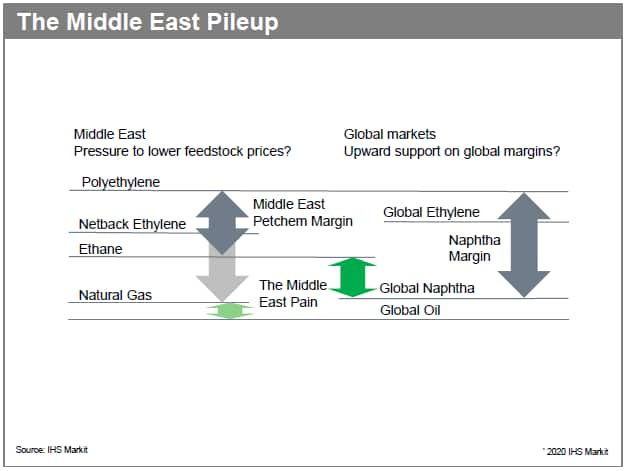

glycol. With fixed, and at least low, advantaged ethane prices set

to stimulate demand the industry has, as a result, seen periods of

extreme profitability. However, with crude prices testing their

historical lows that advantage has disappeared, and it is now

Middle East players who are at risk of becoming the price setters

as their delivered costs are now above those for European and Asia

producers. This is a situation that has briefly been seen in 2015

and 2008 but only for short periods of time and the expectation

that this situation may persist through the rest of 2020 is the

reason why we see this as a period of unprecedented pressure for

the industry. That pressure may be sufficient to raise questions

about the cost structure in the Middle East. Oil and gas producers,

the feedstock suppliers, may be challenged to lower feedstock

prices to ensure the viability of the cracker operations in the

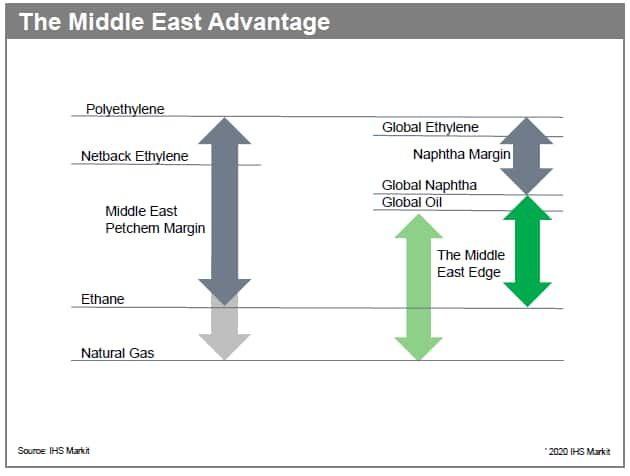

region. The usual Middle East spread of markers from natural gas

through ethane and ethylene to polyethylene has piled up close

together and left the industry at risk of being the highest cost

supplier into many traditional markets, even with its ethane-based

operations.

But the position for Middle Eastern players may not be as challenging as for some in the industry. It is not enough to simply be uncompetitive versus other players to put you at risk, it is the comparative position of suppliers around the world that is critical. Middle Eastern steam cracker operators have two defenses that will give them some protection from the weak crude oil markets. The first is that most have the lowest cost ethane globally, and those that don't use ethane enjoy heavy cross ownership with their feedstock suppliers. If economics become so poor that producers would prefer to cut rates, they may simply not be allowed to cut rates but there may be some concession on pricing to ensure business continuity. In addition, heavy cross ownership between petrochemical producers and oil and gas suppliers means that reducing feedstock prices will ultimately have the same consequence for owners as lowering dividends or incurring losses. The second and more critical factor is that the Middle East has a major cost advantage against one other supply source in delivering product into the major importing market of China. That other supplier is the U.S.

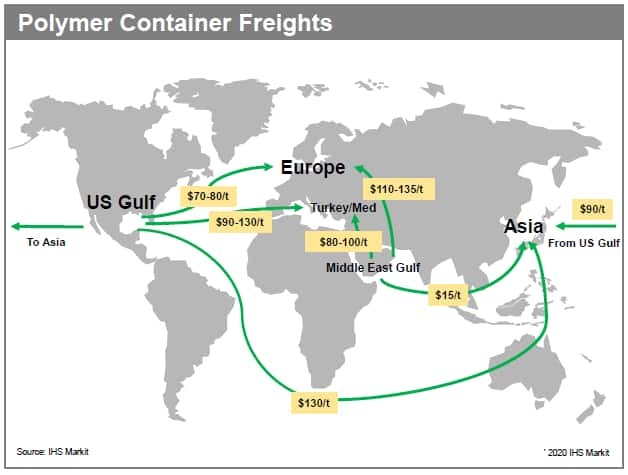

Container freights into China from the U.S., the other major exporter of polyethylene, work out to be around $90-130/t, at the higher end of this range from the U.S.G.C. In comparison, the Middle East is seeing a freight cost to China of around $15/t from Jebal Ali in Dubai and marginally higher from Saudi Arabia. The result is around $100/t lower freight. The Middle East also enjoys somewhat smoother trading relations with China than is the case for the U.S. and better penetration into other Asian markets. This will ensure that in an all-out cost battle, it will be the U.S. who would be the first to flinch.

The other export markets that both players can utilise as outlets are those of Europe and Turkey. Here the position is more balanced and the costs to move product from the Middle East Gulf into Turkey are comparable with those from the U.S. whilst exports into the northern part of Europe see a notable advantage for U.S. product. This may result in something of a challenge for the Middle East to maintain its share in Turkey and Europe. Europe is less of a critical export market and has substantial local supply which, for much of this year, will be advantaged on a delivered basis relative to importers. Turkey has a more prominent position as an importer though the overland route from Iran may give the overall Middle East supply chain an edge relative to the U.S. This leaves the Middle East with a critical cost advantage into its key export market of Asia and should ensure that cash margins in the region remain in positive territory.

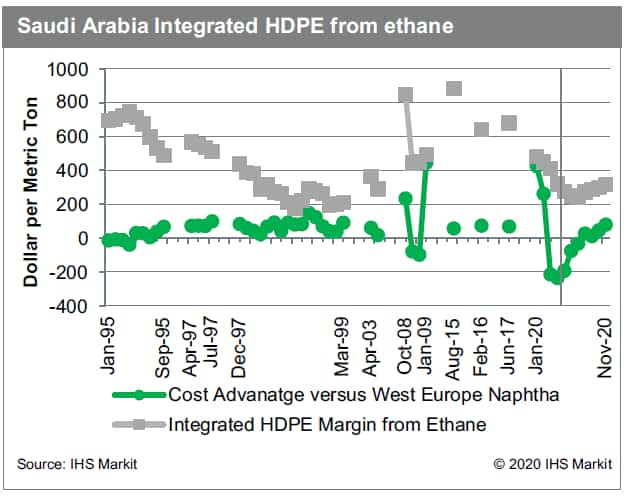

However, to put some perspective on the cost environment, some historical analysis is needed. The Middle East industry has seen some modest cost increases over time, and this has pushed up the crude oil price and therefore naphtha cracker economics at which the Middle East assets can be competitive. Looking back over the history of the industry into periods when crude oil prices where depressed, it is possible to see a number of occasions when Middle East players, even with ethane feedstock, lost their advantage to European operators temporarily; in the financial crisis in the distorted market of Q4 2008 and in the extremes seen in 1995 when the whole industry saw sky-rocking prices. However, at no point has such a long period of such significant disadvantage been seen as that now forecast for 2020. Even during the oil collapse of 1998 and 1999, Middle Eastern crackers maintained some delivered cost edge against European players. When we do look back at those times when Middle Eastern players lost their advantage, which are few, overall industry profitability has been relatively strong. But today, at the same time as crude oil prices are falling, which is resulting in the collapse of the Middle East cost advantage, global profitability, which usually adds to cost advantage, is under pressure. The result is a forecast that keeps regional profitability at historic lows for much of the next 2 or 3 years.

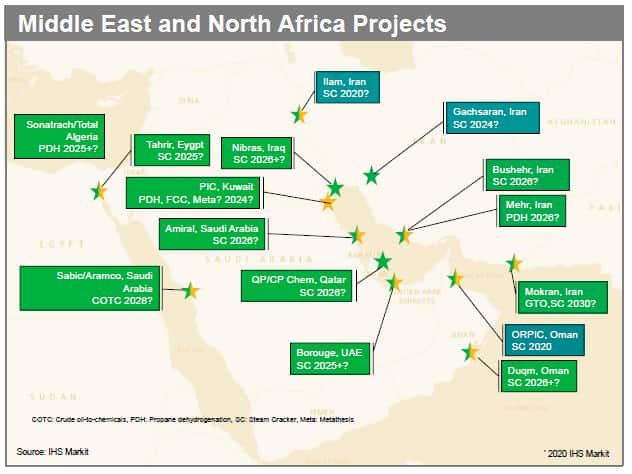

But what of the long-term prospects for the region? The discussions on investment that have re-emerged after the 2014 crude oil crash must once again be at risk of derailing and given the nature of the investors, the likelihood of these projects progressing as previously forecast is remote. The support for investment in the region remains as expectations for feedstock supply growth long term remain and the need to build a secure outlet for oil reserves persists.

But with many of the projects being pushed by oil majors who have seen short- and medium-term outlooks turn deeply negative, the ability for these investments to progress will be severely limited. Even projects which are not so closely tied to oil producers remain a risk as credit availability in the region is certain to be under pressure and it may be close to impossible to progress projects through critical stages in the next 1-2 years, a critical time for many of the projects currently under consideration for the region.

And, the dilemma for the Middle East region is that, once the pandemic passes, it will be left with the same challenges and opportunities as before. How to best utilise hydrocarbon reserves in an oil market that is set to pass its peak demand, and may now even have seen that peak already pass? The rationale for investment has in no way diminished as a result of the current Covid-19 pandemic, it may have increased. It is rather the ability of the oil and petrochemical industry in the Middle East to drive through those investments given the challenge of dramatically reduced earnings and broader fiscal challenges throughout the region.