Navigating the storm: African energy review and outlook

Africa has so far avoided the worst health impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, but its economy and energy sector have been hit hard. The region has experienced its largest economic contraction on record and the energy sector must now navigate through the narrowing straits of a pandemic-induced across-the-board drop in energy demand as well as a looming energy transition. Despite a tempestuous 2020, however, a few silver linings appear on the horizon. Looking back at 2020, what happened in the region's economy, upstream, and gas and power sectors that were of greatest consequence, and what should we expect to see in 2021, as the region focuses on accelerating economic growth and advancing energy projects? In this report, we will review and identify the major issues and events that shaped 2020 and offer an outlook for 2021.

- Sluggish growth. African policy makers are focused on supporting a quick economic recovery, and many African economies are likely to see a rebound in growth over the next year. But debt vulnerabilities and limited fiscal capacity will weigh heavily on the pace of recovery, and political instability remains a concern.

- Energy Transition. African countries will be affected by international oil companies' (IOC) shifting priorities but planned regional divestments will create entry opportunities for willing investors.

- A Transition to Gas? Gas moves up the agenda, but domestic projects are limited and export projects face increasing uncertainty.

- Upstream Oil and Gas Prospects. Shifting global energy fundamentals will lead to increasingly selective exploration and project development across much of Africa.

- Upstream Competitiveness. Increasingly selective upstream spending will put pressure on African countries to improve their fiscal and regulatory competitiveness.

- African Power. Further strain is likely for the power sector but there is potential for the commercial and industrial sectors to play a stronger role.

African policy makers are focused on supporting a quick economy recovery, and many African economies are likely to see a rebound in growth over the next year. But debt vulnerabilities and limited fiscal capacity will weigh heavily on the pace of recovery, and political instability remains a concern.

While the health impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic have been relatively limited in much of Africa, the continent's exposure to external investment and depressed internal markets has meant that the pandemic's economic consequences have hit hard, with the continent recording a historic recession in 2020. In particular, the pandemic-driven oil price plunge has triggered sharp contractions in West Africa's oil-dependent economies, pulling countries into deeper poverty. Fiscal capacity to combat COVID-19's economic impacts are further constrained as many African countries remain deeply indebted to foreign private and sovereign creditors, particularly China. Meanwhile producer and frontier governments alike remain constrained in their ability to control porous borders and suppress domestic and regional threats.

Elections over the past year saw the return of many incumbents including in Togo, Ghana, Burkina Faso, and Tanzania as well as in Guinea and Cote d'Ivoire, where presidents secured third terms. Overall, the results signal policy continuity largely focused on stimulating economic recovery to address current account and budget deficits.

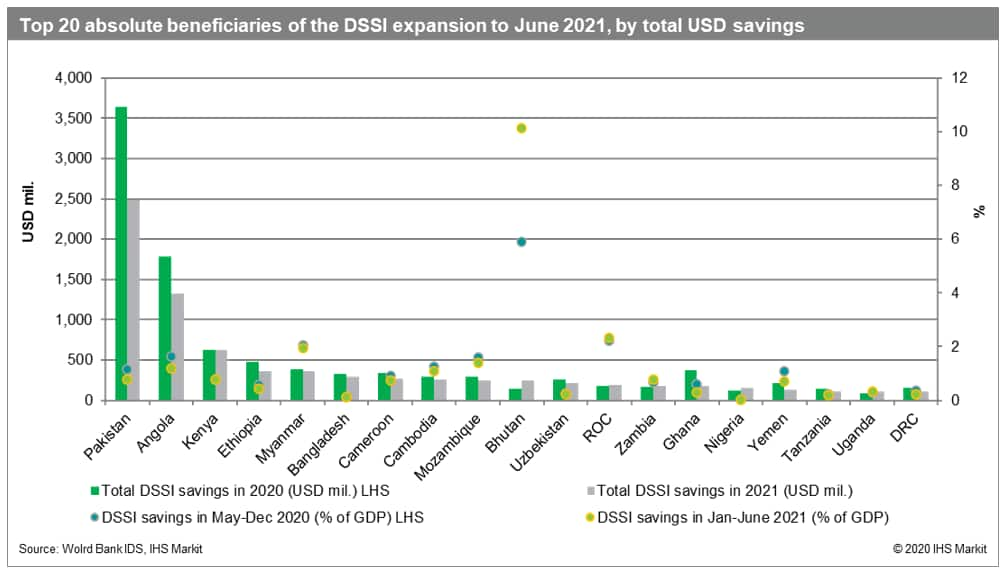

Figure 1: Top 20 absolute beneficiaries of the DSSI expansion to June 2021, by total USD savings

Over 2021, some relief from pressure on fiscal finances and external liquidity will come from the deferral of debt payments under the G-20 Debt Service Suspension Initiatives (DSSI) - debt relief awarded to low-income countries under the International Monetary Fund (IMF)'s Catastrophe Containment and Relief Trust (CCRT) - combined with stronger global oil prices and global trade flows. Still, sluggish growth, COVID-19-related health spending, and rising debt servicing obligations will continue to limit fiscal flexibility. A slow path towards fiscal consolidation over the medium term will furthermore mean that the public sector debt burden will continue to rise, adding to the worsening debt backdrop in the region.

IMF-support programs, such as Angola's Extended Fund Facility (EFF) will, however, introduce a fiscal and monetary policy framework under IMF-program conditions while the government pursues privatization and economic diversification initiatives over the medium term. Cameroon, Chad, and Gabon, whose IMF-support programs expired during 2020, are expected to request successor programs during 2021, with program targets focused on building external buffers and government revenue resilience. Zambia, which defaulted on its sovereign debt in November 2020, is only likely to engage with the IMF in late 2021 to avoid further scrutiny of public finances prior to hotly contested elections scheduled for August. While the acute impact of the pandemic saw South Africa and Nigeria - the continent's two largest economies - seek IMF support - a first for South Africa - neither is likely to proceed with a more formal support program. South Africa's GDP is expected to rebound by 3.3% in 2021, but the unfolding COVID-19 pandemic remains the biggest risk to the economic outlook, with IHS Markit acknowledging the possibility of a third wave during the southern hemisphere winter months. Nigeria's economic rebound during 2021 is expected to be modest, estimated at 1.2% growth GDP, with growth in oil production dictating the outlook.

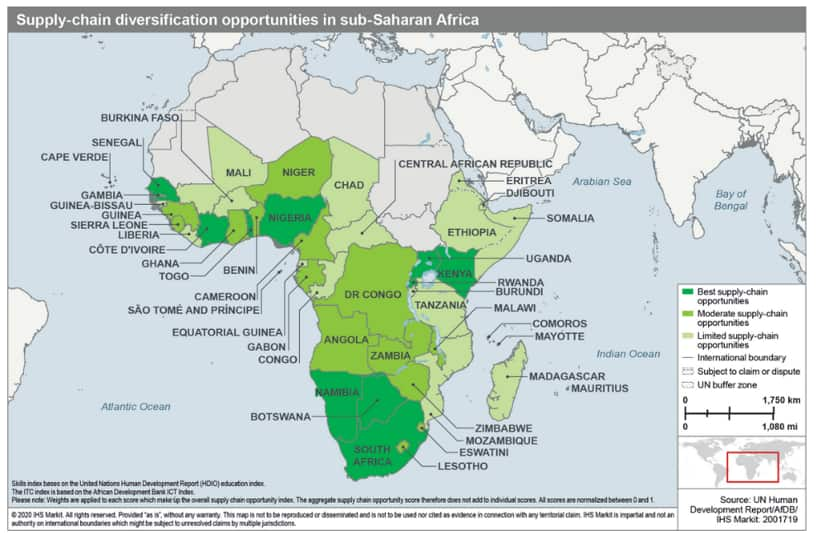

Figure 2: Supply-chain diversificiation opportunities in sub-Saharan Africa

Momentum toward regional integration accelerated over the pandemic - as seen with the African Union (AU)- and private sector-led initiative to support the rapid procurement of personal protective equipment under the Africa Medical Supplies Platform (AMSP), with continued AU-led efforts to establish additional channels for pooled procurement of vaccines as fiscal constraints limit governments' capacity to establish bilateral agreements. Still, vaccine roll-out plans across the region are only likely to gain real momentum toward the latter half of 2021. Similarly, while initially delayed due to the pandemic, on 1 January 2021 the AU launched the African Continental Free Trade Agreement (AfCFTA), which also is the world's largest free trade area. This agreement will create enhanced supply chain diversification opportunities across the continent over the medium to longer term. And the removal of tariffs will provide significant incentives and growth benefits by reducing production costs and enabling businesses to take advantage of economies of scale.

Instability in the Sahel and Horn of Africa - which will see several elections in 2021, most notably in Ethiopia, which is slated for June - undermines multilateral stabilization efforts and threatens to degrade into broader regional conflicts, while growing piracy in the Gulf of Guinea and militancy in Mozambique's Cabo Delgado region are also acute security watchpoints for 2021. In North Africa, Libya's civil conflict is showing some signs of easing with positive implications for oil and gas production, but neighboring Tunisia is struggling to manage its democratic transition with social protests often undermining efforts to expand upstream investment. Within this, some countries stand out in terms of relative resilience. Egypt is in a better position to manage some of the current pressures having set in place economic and energy reforms before the 2014 oil price collapse.

African countries will be affected by international oil companies' (IOC) shifting priorities, but planned regional divestments will create entry opportunities for willing investors.

In 2020, the worst global recession in three quarters of a century coincided with a wave of companies and governments alike committing to net-zero emissions targets. This put pressure on the fossil fuel industry's "social license to operate" and has kept energy commodity prices stuck in low gear. In response, IOCs have sought to reduce their financial exposure and deliver competitive returns on capital to shareholders by refocusing on short-cycle, high-margin developments, and infrastructure-led exploration.

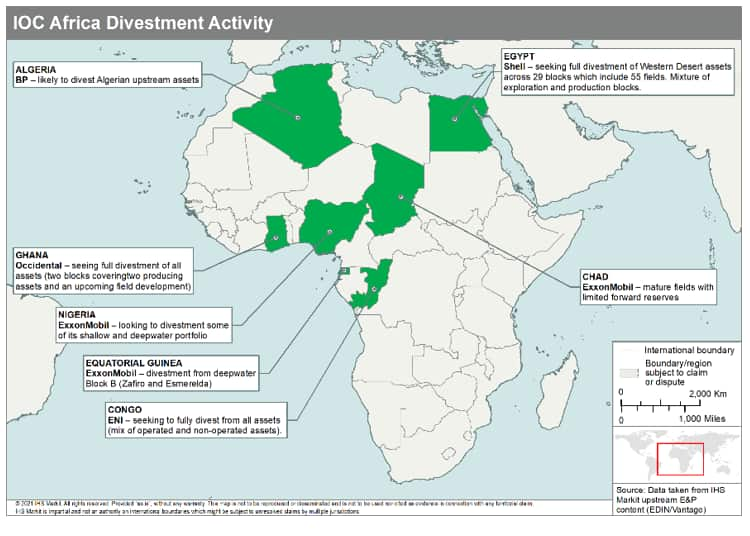

Figure 3: IOC Africa Divestment Activity

Financial pressure on upstream companies, however, is expected to continue into 2021, as IOCs remain focused on reducing high-cost and high-carbon investments while increasing spending on low-carbon electrification and carbon-offset technologies. Accordingly, major IOCs are expected to both accelerate upstream divestments and reduce frontier exploration activity. At the same time, the risk of stranded assets - discovered resources that may not be developed due to price or policy pressures - will increase. But IOC divestments will also present new E&P opportunities for well-capitalized, risk-tolerant buyers that are less strategically constrained by shareholder and policy pressures, including companies such as international NOCs, private equity firms, and commodity traders. Local firms may also increasingly take a role in the domestic upstream. But new players are unlikely to fully replace the technical, social and revenue contributions of retreating IOCs, and domestic NOCs' ability to fill the gaps will be constrained as they continue to struggle financially.

Shifting global energy fundamentals will lead to increasingly selective exploration and project development across much of Africa.

Market uncertainties and low energy prices in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic and sustained by concerns around the energy transition have led operators to defer new projects in the region and delay planned drilling programs. Only two of the 28 African upstream project sanctions expected pre-pandemic were approved in 2020, while several sanctioned project start-ups were also postponed. Additionally, OPEC's enforcement of compliance targets impacted large producers such as Angola and Nigeria, lowering their overall production levels for 2020. While BP and Kosmos pulled back from frontier exploration, Total and Shell added to their respective frontier acreage holdings.

Nigerian and Angolan drilling bounced back relatively quickly into late 2020 and in Mozambique in early 2021 but drilling restarts in other markets such as Congo are likely to be more sluggish. New field wells are expected to be drilled across Angola and Namibia, though the timeline is still uncertain. ReconAfrica's Owambo Basin drilling campaign should reveal the basin's potential for hydrocarbon exploration and provide hints about the potential in analogous basins.

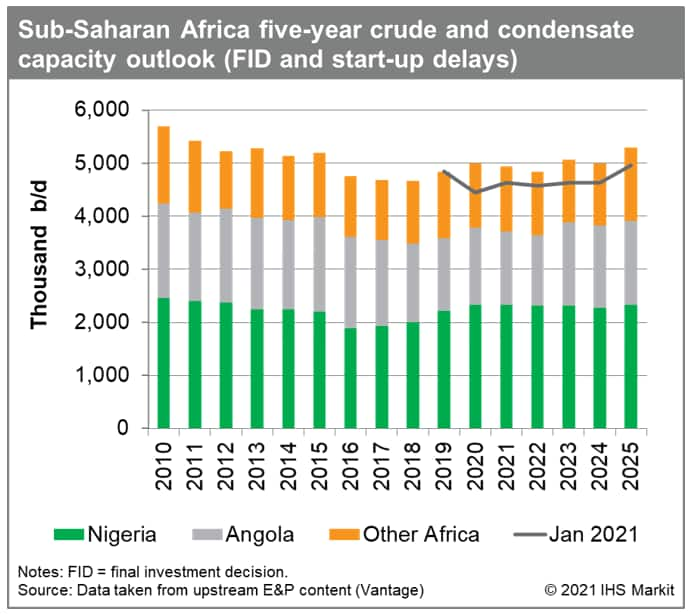

Figure 4: Sub-Saharan Africa Five-Year Crude and Condensate Capacity Outlook (FID and start-up delays)

Following a record low year of CAPEX spend and reserve additions in 2020, the number of project sanctions in 2021 is likely to remain relatively limited, with capital spend down $16 billion from expected pre-pandemic levels. To reduce project costs, most start-ups in 2021 are likely to be situated near field development tiebacks or planned expansions of existing projects. This trend is expected to continue into 2022.

While overall production is due to re-bound in 2021 as drilling restarts and OPEC compliance requirements ease, overall supply levels are not forecast to return to pre-pandemic levels until 2025.

Gas moves up the agenda, but domestic projects are limited, and export projects face increasing uncertainty.

With IOCs refocusing their global strategies towards lower carbon assets, gas is gaining prominence as a transition or "bridge" fuel that advances a lower-carbon energy mix. For Africa, however, the notion of gas as a bridging fuel is more complicated. Most discovered gas reserves are likely to be developed not for domestic markets but rather for export, via LNG, with its characteristically long and now increasingly uncertain development timelines. LNG projects already online faced a challenging market environment in 2020 as global gas prices plummeted on the back of falling demand. And Africa's limited and fragmented domestic gas markets are seeing lower demand due to COVID-19 lockdowns. Reduced demand particularly affected North African countries, markets which have more gas fired electrification and industrial gas utilization than other countries across the continent.

Prospects for African upstream gas projects are mixed. Egypt fired the starting gun for African final investment decisions (FIDs) when both the NEA and NI marginal gas tiebacks were sanctioned in January 2021. In Angola, Chevron is to sanction the Sanha Lean Gas project, as attested to by recently announced large-scale contracting. Nigeria's Aje Gas project may take FID over 2021 but is facing financing concerns. A 2021 FID for Libya's Bouri Phase 2 project is largely dependent on the progress of Libya's UN-backed peace negotiations. While no major gas development projects are due online over 2021, several smaller projects are expected to commence production, including the Alen Gas Hub in Equatorial Guinea and the delayed Raven and Elan start-ups in Egypt.

Almost 40 Bcf of LNG projects that were stalled over 2020 are expected to make further progress over 2021, though likely at a slower pace than previously expected. Intensifying Islamist militant activity in Mozambique, which the government and foreign partners are struggling to control, has put at risk the planned timeline for the Mozambique LNG and Rovuma LNG developments. The reevaluation of development concepts aimed at reducing costs and increasing competitiveness is also underway in several projects across the continent, with a major restructuring at Senegal's Greater Tortue already announced and another taking place at Rovuma LNG. In terms of domestic supply development, both route to and size of market remain key issues and in some cases risk limiting oil and condensate production. Ghana already increased gas flaring and reinjection over 2020 to support oil production and likely needs to continue to do so given recent announced plans to import LNG. And gas commercialization pathways are still unclear for several planned domestic projects including Cameroon's Etinde MLHP-7 field and South Africa's Luiperd and Brulpadda fields.

Increasingly selective upstream spending will put pressure on African countries to improve their fiscal and regulatory competitiveness.

Bid rounds that were stalled in 2020 are expected to resume in 2021, along with the launch of new license rounds. While bid rounds in Angola, Gabon, Mozambique, and Senegal will serve as barometers for investor appetite, governments that offer investors a flexible and accommodating contractual and regulatory environment are expected to have an upper hand in attracting new drilling.

Below are other key market developments to look out for:

- Algeria. Algeria is on track to promulgate new regulations under the new hydrocarbon law by mid-2021, though as the timetable has slipped before there is a risk it will happen again. Nevertheless, the country's improved fiscal and contractual terms have piqued investor interest, which could lead to a resurgence in near-field developments and enhanced recovery projects if the government can demonstrate that it truly is cutting red-tape.

- Nigeria. Progress on the petroleum industry bill (PIB) is possible in Q1 2021. But even if the PIB is passed, it is unclear whether its terms will spur sufficient investment in deep-water developments to lead to a much-needed revival in the sector.

- Egypt. A new deal with TransGlobe allowing the company to develop existing brownfield fields under an updated contract that provides significantly improved fiscal terms demonstrates the government's desire to support investment into more marginal assets and to maximize the country's remaining oil resources. Negotiations have taken over two years to complete but should pave the way for other small operators to navigate upgraded agreements and help with the government's efforts to revitalize interest in maturing areas. This deal may also serve as a model for other countries that seek to do the same.

- Senegal. An emerging producer, Senegal's efforts to harness investment in its hydrocarbon potential have been stymied through repeated delays to its first bid round, which has been extended three times and is now due to close at the end of May.

Further strain is likely for the power sector but there is potential for the commercial and industrial sectors to play a stronger role.

Industrial power demand declined across Africa due to the COVID-19-induced strain on the economy. Some markets in Sub-Saharan Africa, however, such as Nigeria, saw an overall increase in power demand owing to the increase in electricity intensity in the residential and commercial sectors, a product of suppressed power demand. Despite the increase in these markets, however, overall demand growth was lower than expected.

Power demand recovery post-lockdowns will place significant pressure on already strained power systems facing capacity shortages, including South Africa. Investment from private players and multinational institutions will be essential to addressing power supply deficiencies. However, the uncertainty created by the pandemic, as well as the strain on financial resources, delays in project permitting, changes to sovereign risk ratings, and the devaluation of local currencies, will put projects in the pipeline at risk. Corporate power offtakers will play a more prominent role going forward, either by investing in renewable self-generation projects or serving as offtakers to large-scale projects under power purchase agreements. Solving regulation bottlenecks around direct sales will be crucial to unlocking this potential across the region.

Looking further out, planned changes to the power mix in South Africa and Nigeria to increase gas and renewable generation face funding uncertainty. In South Africa, 45,900 megavolt-amperes (MVA) of new network assets are required to support planned capacity additions through 2028. In Nigeria, supply shortages continue to constrain gas-fired generation due inadequate gas infrastructure, maintenance issues, and malicious sabotages. Power evacuation and water management issues also continue to strain supply.

Moreover, there will be pressure on countries to increase their nationally determined commitments (NDCs) both ahead of the COP-26 meeting this November, and afterwards. While very low tendered prices for renewables are putting pressure on gas-fired power generation projects, protracted low LNG prices make LNG import projects relatively more attractive than major pipeline delivery routes especially when these entail cross-border issues. Coal phase-out remains a key issue for South Africa, focused around the retirement program for Eskom generation, while new coal plants are severely underperforming and the state utility is in fragile financial health. Coal is also under pressure more broadly across Africa - projects have been cancelled in Kenya, Egypt, and elsewhere - though this is as much due to surplus capacity in the face of slowing electricity demand as to environmental pressures.

Learn about our Africa petroleum sector risk profile offerings.

See more information on our well, field & basin summaries.

Learn more about our solutions for asset evaluation, portfolio view, and production forecasts.

See offerings for detailed E&P activity coverage and context by country/territory.

Learn more about our regarding our global power and renewables service.

Learn info about country risk services for Africa's overall country risk outlook.

Learn info on Africa's macro-economic outlook through our economic offerings.

Posted 8 Feb 2021

This article was published by S&P Global Commodity Insights and not by S&P Global Ratings, which is a separately managed division of S&P Global.