New Zealand gets in on the decommissioning act

Introduction

In May, we published a blog post, "Australia's new decommissioning

regime: following the UK's lead" (

https://ihsmarkit.com/research-analysis/australias-new-decommissioning-regime-following-the-uks-lead.html).

The post outlined how the Australian government, stung by having to

pick up the bill for decommissioning work on the Northern Endeavour

FPSO, was taking action to ensure it did not happen again.

The government of New Zealand had a similar experience in 2019, when the permit holder for the Tui field, Tamarind Taranaki, went into liquidation, and was unable to complete the decommissioning. The government has now started the expensive job of decommissioning itself. Determined not to repeat the experience, New Zealand is now following Australia, taking action to safeguard itself from similar occurrences in the future.

What is New Zealand doing?

In June 2021, the New Zealand government produced the Crown

Minerals (Decommissioning and Other Matters) Amendment Bill. If

passed into law, the bill will amend the Crown Minerals Act 1991,

the main upstream framework law for petroleum (and other minerals).

The main changes proposed by the bill are as follows:

- Decommissioning responsibilities will have a consistent legislative basis instead of being included as conditions attached to specific licences.

- Trailing liability will be introduced so that previous holders of permits/licences may be responsible for decommissioning.

- There will be a requirement for financial guarantees to back up decommissioning obligations.

- Stricter monitoring of the financial strength of rightholders to ensure they can meet their decommissioning obligations. Permit/licence holders which have not submitted a development plan which includes decommissioning plans will be required to do so. There will also be an asset register to list all the assets that must be decommissioned.

- Penal sanctions, including fines and imprisonment for breaches; highest fine is three times the cost of the decommissioning.

- Post-decommissioning fund to be paid into by permit/licence holders to cover any future costs of remedial work to already-decommissioned wells and infrastructure, which proves necessary at a later date.

The changes will apply to both current and future holders of permits/licences.

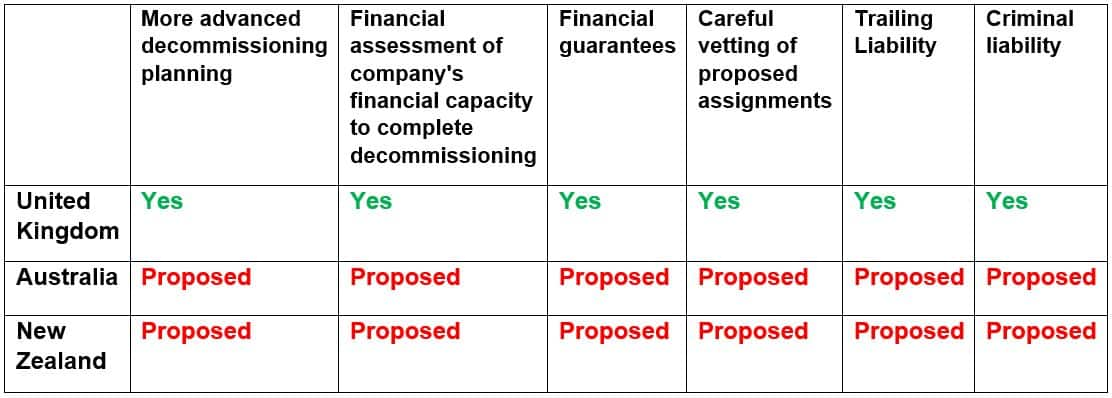

New Zealand v Australia v UK

The proposed approaches of Australia and New Zealand are noticeably

similar, and both are influenced by the experience of the United

Kingdom, as shown by the following table:

The New Zealand government's recent Discussion Document -

Proposed Regulations to support the Crown Minerals (Decommissioning

and Other Matters) Amendment Bill 2021 from July 2021 expressly

mentions the influence of mature producers, including the UK and

Australia, on the current reforms.

What does the industry think?

For the most part, the New Zealand government's proposals are

likely to be seen as unfavourable to investors (though there may be

changes before the final version of the bill is passed). In

particular, the process of assigning petroleum rights looks set to

become more complex. Proposed assignors will need to conduct

tougher due diligence into their intended assignees. In addition,

trailing liability has the potential to create uncertainty for

companies and directors long after they have divested themselves of

an upstream asset. That said, the industry probably accepts that a

more comprehensive decommissioning regime is necessary.

What happens next?

The bill is open for public submissions. The government is aiming

to have the bill passed before the end of the year. The government

is also planning to publish a set of regulations in late 2021 or

2022 to add further detail to the proposed amendments in the

primary legislation.

Conclusion

Whatever happens with the current New Zealand decommissioning bill,

it is clear that governments are becoming more aware of the risk

that governments/taxpayers may have to fund decommissioning work

when the last oil company producing from a field goes out of

business without finishing the work.

They are also aware that avoiding this scenario requires planning

and action well ahead of time. By the time a company goes bankrupt,

it's too late.

Find out how we can help you screen upstream opportunities and above-ground risk with PEPS from IHS Markit.

This article was published by S&P Global Commodity Insights and not by S&P Global Ratings, which is a separately managed division of S&P Global.