Article: Special Report: The world is looking beyond India for supplies of mango purée

This is an article taken from our IEG Vu dated 05/06/20.

Mangoes are grown all over the world, yet the number of countries producing mango purée and/or juice for sale on global markets is quite small.

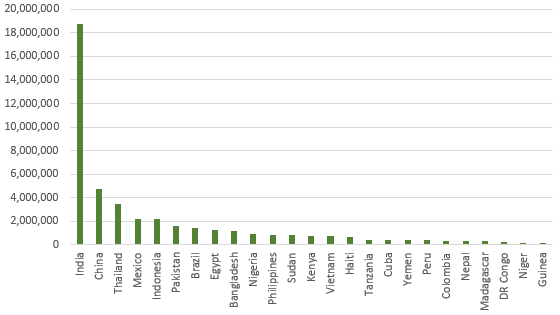

India is by far the world's largest producer, producing around 20 million tonnes of mango annually. Ten years ago this figure was around 10-11 mln tonnes, but India has steadily increased its mango production. The sheer scale of Indian production is amply shown in the accompanying chart, below.

World's top 25 largest mango producers in 2018 (tonnes)

The vast majority of India's production is destined for the fresh market. Mango is a fresh fruit that is impossible to store for long periods of time unlike, for example, apples, and while it can be grown around a large part of the year, according to geography, the new season fruit is eagerly awaited halfway through the year.

As for processing, India does some IQF mango, but the big processing is for chutneys and pickles, beloved on the domestic market and abroad. The UK is the country's biggest customer, taking about 16,000 tonnes annually. Frozen mango is also exported to be used in pickle production elsewhere in the world: the Patak brand, for example, manufactures products in the UK.

This season apart, India's distribution of fresh mango is well organised and India still only processes about 7% of its fruit into juices and single strength or concentrated purées. The country has a production capacity of around 700,000 tonnes of finished product, but actual output is around 450,000-500,000 tonnes annually.

China produces nearly 5.0 mln tonnes of the fruit annually but is entirely absent on the global juice market. If any fruit is so processed, it is sold domestically or to very local markets.

Colombia, on the other hand, produces around 350,000 tonnes of fruit annually but annual production is around 40,000 tonnes.

Thailand's production is some 3.5 mln tonnes, and the country produces very little juice and purée and what it does produce is consumed domestically. The country, like the Philippines, another large grower, tends to produce large quantities of dehydrated mango.

Then there are countries in Africa such as Sierra Leone that grow and process mango, but the processing plants are often small, inconveniently located in relation to transport links and not very efficiently run. This, and a frequent lack of certification to modern standards, mean that African processed mango is a rare sight on international markets.

Indian mango production is likely to drop by 4% to 20.44 mln tonnes this year, according to the country's agriculture ministry. IEG Vu thinks this is optimistic. Reports from India tell of large quantities of fruit left unharvested, and huge problems in transporting fresh fruit (which is a huge market) across the country. Production may very well be as claimed, but we think the wastage is likely to be huge.

Processing of mangoes (Alphonso, Totapuri, etc) from southern and western India has started, while the season in the northern states like Uttar Pradesh will begin from mid-June onwards. These two varieties are dominant when it comes to purée and juice, but other varieties are also processed for beverages, notably Kesar (which is becoming increasingly popular), Tommy and Sindura, which is sometimes used to blend with Alphonso to keep the cost down.

Whatever happens to Indian production this season, there are still some inherent problems in the industry. The first is the over-capacity. Smaller suppliers have gone out of business, but others set up to replace them and there are companies that pretend to be processors, but which in reality own no plants themselves and merely sub-contract the work to others. A lot of these companies have no certification acceptable to European markets, though they may pretend they do. Their numbers are reducing , though, and in time they will disappear - possibly quickly, after this season.

Another factor is the swift trend towards bulk packing rather than in cans. Canned production continues and is estimated at around 25,000 tonnes of finished product last year. Processors have moved swiftly towards packing in drums of flexitainers. This is partly due to customer demand and partly for quality reasons. However, foodservice customers (in particular) both in India and abroad like large cans because they are easy for portion control and there is no wastage and so IEG Vu does not think this form of packing will disappear entirely.

Then there is the issue of adulteration. Smaller Indian processors (see above) have an unenviable reputation for blending old crop production with new. There is nothing wrong with this, as long as it is sold as such, but sometimes it is not. Its shelf life is thus rather shorter than 100% production from new crop. Alphonso purée is frequently 'cut' with Sindura, while blending of old and new stock can be found in any variety of fruit.

Assuming that supplies from India will be expensive this year, some potential buyers are looking around for alternative origins.

Pakistan exports fresh mango and makes purée. Fresh exports are going to be down maybe around 80,000 tonnes, this year.

Its best-known product is the Chaunsa variety, which is comparable to India's Totapuri. Unfortunately, Pakistan has certification problems with some countries. Its main export markets tend to be in Asia-Pacific and the Middle East, which are less discerning (and where, in the case of the Middle East, there is a ready and waiting market of expatriate workers). However, this year construction work has stopped in the Gulf States, and many workers have returned home, so this market is likely to be unpromising.

Bluntly, IEG Vu does not see Pakistan as being a viable volume player in the European market for the next few years at least.

South American product is popular in the US, not least because it is relatively quick and easy to ship. Colombia has Magdalena as its premium product, and also grows varieties such as Kent and Tommy. The country has planted more land to mango in recent years and the trees are now coming into bearing. There might have been 100,000 tonnes of fruit available before Covid-19 hit, but production is likely to be down.

However, Magdalena purée is very keenly priced at the moment and is duty-free into Europe. Colombia could have a price advantage of USD100/tonne.

Peru also grows similar volumes to Colombia and its premium product is the Chato Da Ica variety, which is sold only in single strength form and is regarded by some as a worthy rival to India's Alphonso. It is generally priced close to Alphonso as well. It is popular in the Americas but unlikely to find many buyers in Europe as it is a mango for the cognoscenti (as is Alphonso) and there are simply fewer Latin American potential buyers than there are Indian.

Brazil grows between 1.5-2.0 mln tonnes of mango and also processes the common varieties such as Haden, Tommy, and Kent. IEG Vu understands that both European and American buyers have been paying closer attention to Brazil this year. Everything will depend on price. The same applies to Mexico, which grows about 2.0 mln tonnes annually. IEG Vu understands that more fresh fruit is going to frozen this year and juice/purée production will be down due to all the usual social distancing and labour constraints.

This article was published by S&P Global Commodity Insights and not by S&P Global Ratings, which is a separately managed division of S&P Global.