The new dynamics of upstream supply and spending after COVID-19

Every oil price collapse over the past four decades—1986, 1998, 2008, and 2014—sparked a similar concern: a steep decline in cash flow could soon lead to underinvestment and oil shortages (1) . But this did not happen. Will the COVID-19-induced price collapse be different?

Oil companies spend money investing in new supply, reducing debt, paying dividends, buying back stocks, and making acquisitions and other investments. But 2020's sharp revenue decline and other circumstances create unique challenges. Oil companies must navigate tough spending choices that have not been present in previous downturns. Four factors illustrate the challenges:

- The future of oil demand after COVID-19 and the energy transition. The leading uncertainty for the entire industry is the trajectory of oil demand. The epic 11 million barrel per day (MMb/d) drop in world oil consumption this year erases nearly a decade's worth of demand growth. Demand is rising after hitting bottom in April, but repercussions from COVID-19 in terms of personal behavior and government policies - including support for carbon-free energy - make the future of fossil fuel demand more uncertain than ever. How much will companies invest in new supply with demand so uncertain?

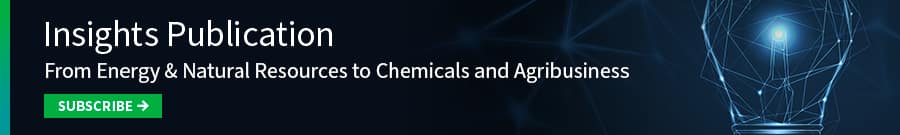

- Oil company debt levels are reaching an all-time high. The collective net debt of 55 globally listed international oil companies, national oil companies, and exploration and production companies is expected to rise to an all-time high of $960 billion by year-end 2021, up some 14% from year-end 2019 (see Figure 1). Paying down this debt will soak up substantial amounts of cash flow in the years ahead. Furthermore, the total-debt-to-total-capital ratio is projected to rise from 33% at year-end 2019 to 36% at year-end 2021. This is higher than the 30% ration at the end of 2014. Additional asset write-downs are likely in coming quarters, further inflating debt ratios.

- Investor disenchantment with oil - particularly with the US upstream industry. The past decade saw an enormous flow of capital to the US upstream oil industry, which fueled record-setting production growth. However, financial returns were poor. Access to new capital is encumbered by lackluster financial performance, uncertainty about demand and oil prices, and investors' increasing focus on the impact of climate change policy.

- Little upstream cost deflation, unlike in 2014-16. Upstream capital spending fell by some 50% from 2014 to 2016, but capital costs also fell 27% (2). Lower costs supported supply growth, despite the price collapse. A much smaller decline in upstream costs is expected this time around as most of the "fat" has already been cut. Upstream capital costs are expected to fall by just 3% by the end of 2020 relative to 2019, but capital spending will be down over 30% over the same period.

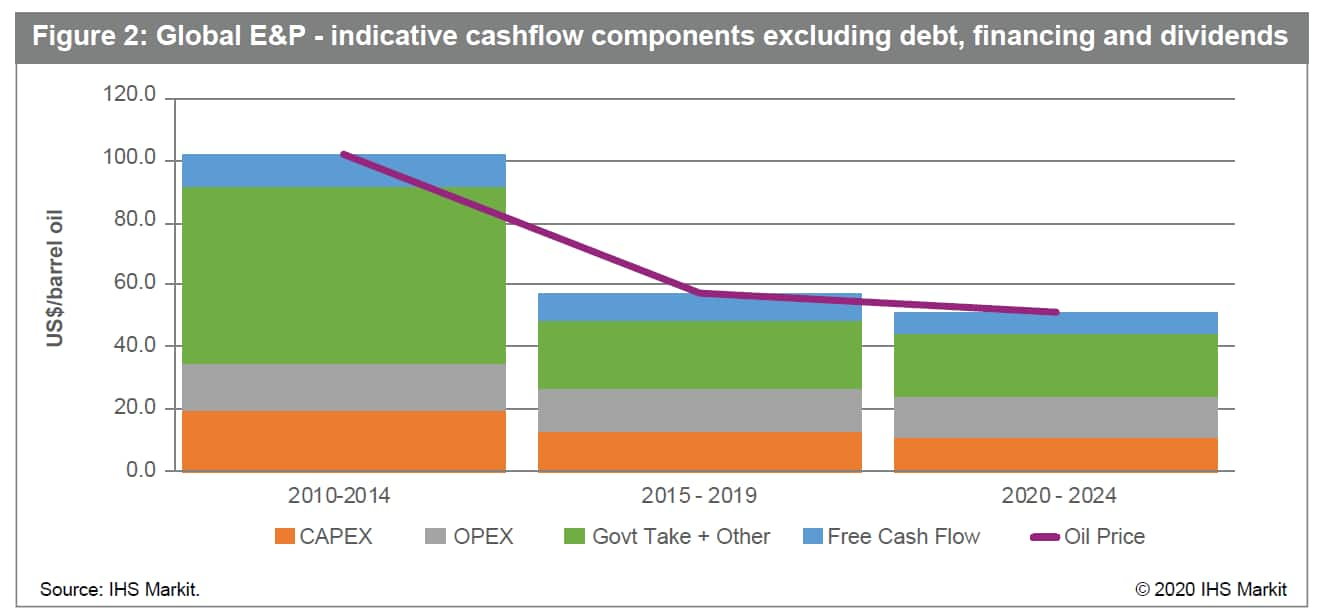

How much money is needed to develop new supply and sustain existing production to meet demand in the years ahead? There is no pre-determined level of future oil and gas demand that supply must meet. But to create some sense of how much money may be needed, we have used the assumptions in our base case—the Rivalry scenario—for oil demand, supply, and price to year-end 2024. These include annual average dated Brent prices ranging from $40 to $65 per barrel (bbl) and our estimates of future spending required to enable supply to meet demand. Our Rivalry scenario assumes a COVID-19 vaccine is in place by 2021. We have also used relationships between reported free cash flow, spending, and oil price from our company metrics database to inform the forward projections. Based on these analyses, we estimate that $4.5 trillion is needed for the global upstream industry to develop new supply (with capex) and sustain production (with opex) to meet demand in the five years from the beginning of 2020. That's similar to the spending in the prior five years. Figure 2 illustrates our calculations.

Will there be enough money from selling oil and gas to fund this spending? The short answer is yes, based on our analysis and assumptions. Although free cash flow for the industry from 2020 to 2024 is less than the prior five-year period, the story is more promising on an annual basis after 2020. Free cash flow rises from a low of $2.5/bbl in 2020 to $9.2/bbl in 2024, allowing the industry to significantly improve cash flow after 2020 and spend enough money to meet the projected level of demand.

But these free cash flow estimates exclude upstream companies' commitments to repay debts and to make dividend payouts and repurchase shares. Overall, the additional pressures on the industry to control debt levels, improve returns, and minimize emissions could lead to spending choices that reduce upstream spending below this outlook.

By any measure, 2020 will be an annus horribilis for the oil industry and governments dependent on oil revenue. Free cash flow of $2.5/bbl for the industry is well below the previous decade's 2015 low point of $4/bbl. That drop understates the total hit to company revenues, as global production will be lower in 2020 compared with 2019.

Higher prices would improve financial performance, assuming cost inflation is contained. But they could also lead to more pressure in large oil-consuming markets to move away from oil and accelerate the energy transition.

The benefit of higher prices is also shared between oil companies and host governments. For example, when annual average Brent prices were near or over $100/bbl from 2010 to 2014, the amount of revenue attributed to "government take & other" (3) accounted for some 55% of the revenue generated per barrel. But after the 2014 oil price collapse, the share of government take declined, falling to 36% in 2016.

In any case, the projected price recovery paints a cautiously positive picture of the upstream industry - particularly from the dismal perspective of the 2020 COVID-19 crisis. But tough choices lie ahead.

Footnotes: (1) Cash flow is the money generated from operations. In the upstream industry, it is revenue from selling oil and gas. (2) "Upstream capital spending" is based on IHS Markit estimates of E&P capex excluding the liquefied natural gas midstream. Cost reductions quoted reflect the changes in IHS Markit Upstream Capital Cost Index, which is referenced to a fixed portfolio of developments to reflect changes in supply chain costs. Opex costs are excluded here. (3) For the purposes of this note, "government take & other" is simply the value in the barrel, which is not attributable to spending and free cash flow to the oil companies and government entities with an equity share of

This article was published by S&P Global Commodity Insights and not by S&P Global Ratings, which is a separately managed division of S&P Global.