Understanding policy and regulatory responses on the upstream petroleum industry greenhouse gas emissions

Moving targets: a complex, evolving regulatory and policy situation

Over the past two years there has been renewed international momentum and drive for an intensified policy response to climate change. IHS Markit's research shows the number of countries with net-zero goals increased from 10 in 2018 to over 100 in 2021, representing approximately 70% of global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions.

Since the petroleum sector directly or indirectly accounts for nearly 40% of global GHG emission, governments are taking steps to develop practical policies and legislation to address GHG emissions including these directly affecting the energy sector and the upstream petroleum industry specifically.

Alongside intensifying government policy responses, we are seeing a wave of climate-change litigation directed at governments and petroleum companies. This creates further uncertainties for the upstream petroleum industry, with more cases being heard in an expanded set of jurisdictions and new legal arguments being advanced in suits targeting both governments and companies.

Whereas US cases are concentrated at the state level focusing on government action to cut emissions, European litigation increasingly scrutinizes and challenges government energy policy, licensing processes, and project approvals in the light of zero-carbon goals, with corporate strategy as well, now a point of legal focus. Furthermore, recent cases involving Super-Majors highlight the potential impact of climate litigation on upstream companies and the ability of the courts to extend their reach into core industry practice. The breadth and complexity of climate-related cases is evolving rapidly as plaintiffs leverage Paris Agreement commitments and climate science to develop legal challenges that question the alignment of upstream policy with carbon targets and, in some cases, push for more ambitious emissions cuts.

Turning up the regulatory heat on upstream petroleum companies

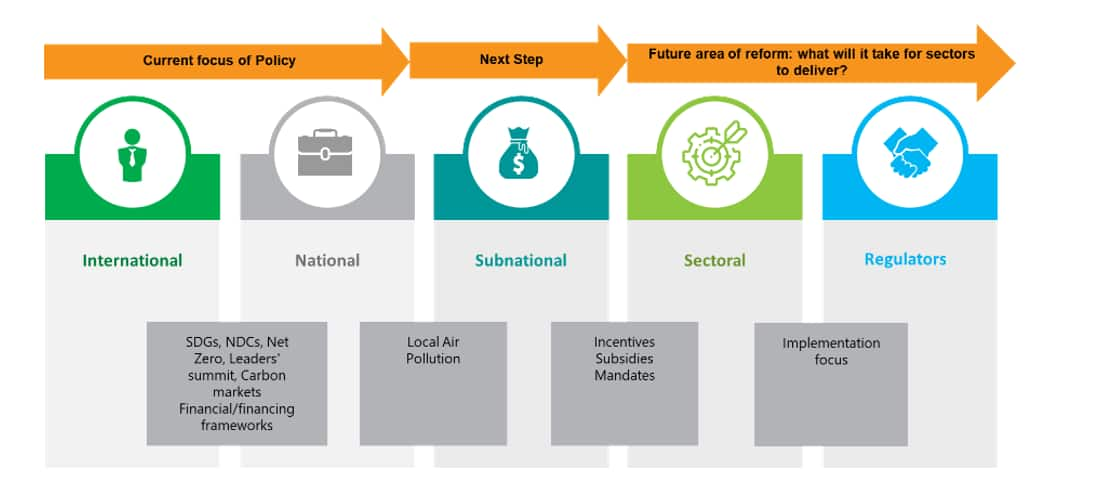

Against this backdrop, upstream petroleum companies find themselves under increased pressure to act from all stakeholders: governments, financial institutions, civil society, and shareholders. As such GHG emissions have become a leading sustainability indicator with cascading policy and regulatory frameworks and overlapping influences requiring company compliance. Companies that operate across numerous jurisdictions need to understand and navigate multiple regulatory policy environments. It is anticipated that in mid-term the regulatory focus will shift from the broader national policy level to specific sectoral policies with regulatory regimes targeting framework implementation by upstream petroleum companies.

Figure 1: GHG Emissions Accepted Framework

To date, addressing GHG emissions has presented many economic challenges both in developing and implementing such measures, with a heavy reliance on government subsidies, investment, and support.

Under control? Relative certainty vs relative uncertainty

The accepted framework for categorizing GHG emissions from industrial operations classifies these into Scopes 1-3. Scope 1 and 2 emissions include those which are under direct control of petroleum companies in their operations while Scope 3 includes indirect downstream emissions that occur in relation to the consumption of the petroleum companies' production. Scope 1 & 2 account for a relatively small percentage of the overall sector emissions compared with Scope 3 emissions which account for the majority.

While under constant review, measures and associated policies, laws and regulations aimed to address Scope 1 emissions (deriving directly from company operations) are typically relatively well known and legislated for in some jurisdictions, however their implementation is not adopted universally across the globe. These include the following:

- Strict environmental qualifications to hold relevant upstream licenses

- Reduction or elimination of routine flaring and venting

- Leak monitoring, detection and repair schemes aimed predominantly at reducing methane emissions

- Use of Carbon Capture Utilisation and Storage technologies (enhanced recovery techniques and reinjection of associated gas)

- Improvement in energy efficiency of equipment and installations

- Electrification (instead of diesel or other fuels use) for powering equipment and machinery

- Installation of vapour recovery units

- GHG Emission Reporting

Measures to address Scope 2 emissions, which derive from energy purchased by a Company, include the following:

- Permitting process

- Energy conservation

- Efficiency upgrades

- Switches to low-carbon electricity to power operations where feasible

- GHG Emission Reporting

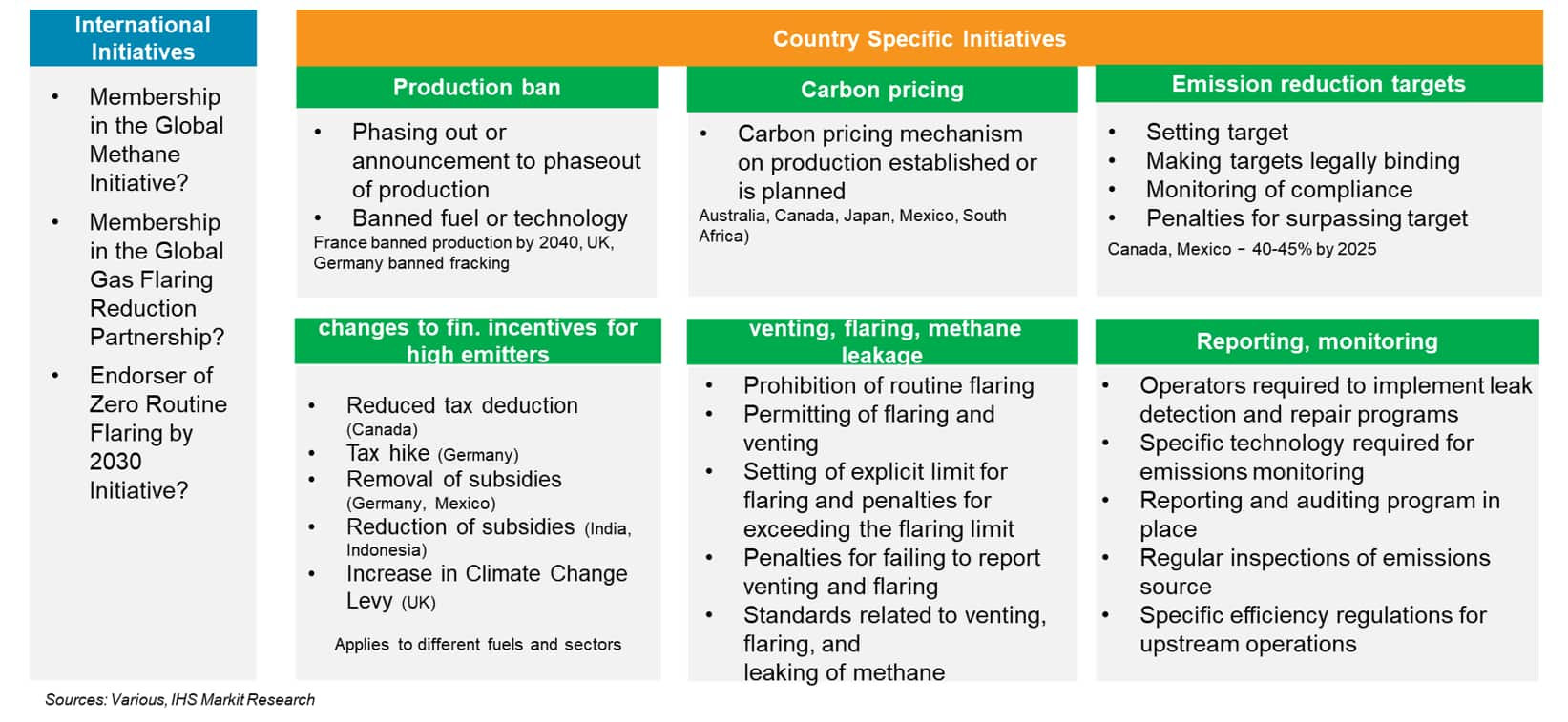

Some policy tools and mechanisms that are used to account for, reduce and eliminate predominantly Scope 1 and 2 GHG emissions deriving from upstream petroleum industry are summarized in the figure below:

Figure 2: GHG Emissions Country Specific Initiatives

IHS Markit analysis suggests that companies can reduce Scope 1 and 2 emissions by up to 30-60% over the short to medium term, with moderate capital investments. These opportunities lie primarily in the areas of energy and operational efficiency, methane containment and incorporation of low-carbon power sources as described above.

While the policies, laws and regulations to significantly reduce or eliminate Scope 1 and 2 emissions continue to evolve in some jurisdictions, dealing with Scope 3 emissions presents a much more uncertain picture.

By and large, Scope 3 emission reduction measures are yet to be defined, agreed, and sufficiently regulated by governments and/or be voluntarily adopted by companies.

Numerous policy consultations, regulatory developments, and potential pilot schemes are under consideration in an increasing number of jurisdictions. Some potential policy measures may include:

- design and implementation of sectoral decarbonisation policies

- changes to upstream petroleum licensing regimes

- offering offsets and investing in low-carbon technologies

- transparent and consistent reporting of Scope 3 emissions

- enabling customers to lower their emissions through increasing use of renewable products

It is noted that companies are also taking proactive steps to address these emissions as well, for example, by way of announcing targets to reduce either their upstream emissions or overall operational emissions.

What can companies do?

The global challenge of climate change continues to precipitate a complex array of responses, largely at the national level, with each country adopting its own strategy and timetable to tackle the issue. This trend is expected to accelerate in the coming years. The evolving regulatory and policy framework is becoming ever more complex with an increasing number of stakeholders involved across multiple jurisdictions.

This rapidly changing framework creates a unique set of opportunities and risks for companies and necessitates a strategic response to the inherent challenges.

It is anticipated that the pace and breadth of changes will only intensify as sub-nationals, industry sectors and regulators are increasingly involved, policies being more volatile and regulatory burden being increased. For companies operating across many countries this creates a monitoring challenge to remain current on the latest developments and to plan compliance programs accordingly.

Companies whose operations are exposed to regulatory risk may consider the potential competitive advantages in understanding and acting on those risks in a timely fashion. Equally, opportunities may arise to benefit from evolving government policies through strategic investment decisions and engagement with government agencies.

Companies that establish a methodical, structured approach to monitoring, understanding, and engaging in the evolving regulatory and policy environments relevant to their operations and strategic objectives may find themselves in the best position to navigate these changing landscapes.

Learn more about IHS Markit Energy Transition Policy and Regulatory Monitoring.

Posted 8 Sept 2021

This article was published by S&P Global Commodity Insights and not by S&P Global Ratings, which is a separately managed division of S&P Global.