What does China’s red-hot summer LNG market mean for imports in the coming winter?

Following a price spike in the December 2020 and January 2021 winter season, China's domestic wholesale LNG prices settled down by March 2021 but picked up again shortly after. By the end of August 2021, the national wholesale LNG price averaged 6,000 yuan per metric ton, about $18/MMBtu. This is more than double the price level last August and already in a price range typically not reached until winter seasons. Such uncharacteristically high shoulder season prices increase the likelihood of even higher prices in the upcoming winter season, which starts in mid-November.

There are several key drivers behind this phenomenon. While pipeline gas prices are largely regulated, China's domestic LNG market prices are deregulated and reflect supply and demand dynamics. Demand for LNG can serve as a proxy to understand piped gas supply availability since end users will seek LNG, which is typically more expensive than piped gas, when piped gas supply is inadequate.

- Demand. Gas demand grew robustly in the first half of the year, 15% year on year. This was the result of a cold winter and an early summer, strong economic and industrial activities, local coal-to-gas switching programs, and high power demand growth at the time of limited generation from coal and hydro power. This led to competition for piped gas supply for industrial, citygas, and gas storage injection use, forcing some players to turn to the domestic LNG market.

- LNG supply cost. The high demand also pushed feed gas costs up for LNG liquefaction plants in key producing regions like Inner Mongolia and Shaanxi. Looking at the other source of supply into the liquid market—trucked LNG out of receiving terminals, the average landed imports price increased 41% year on year in July, and North Asian spot price is at a record high for summer months.

- LNG supply availability. Liquid-out volumes from LNG terminals also dropped in June and July as more gas was needed for the pipeline system.

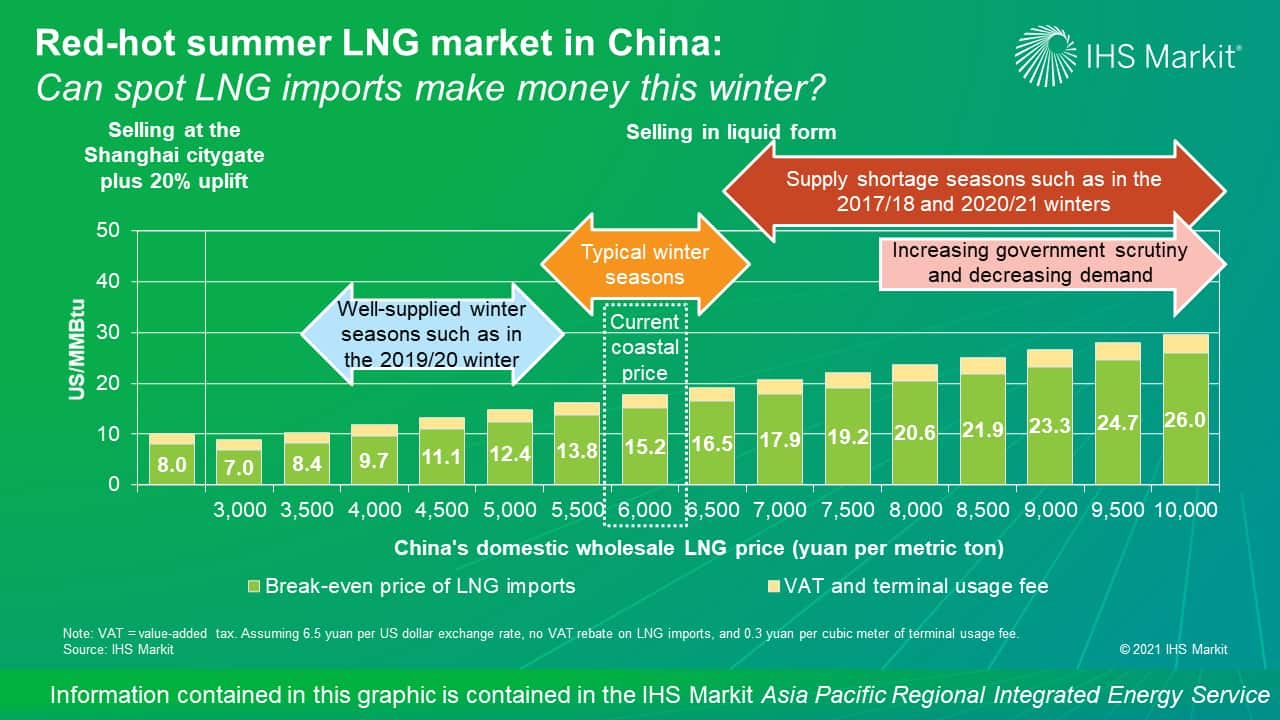

High domestic summer prices signal the potential for even higher prices in this upcoming winter. Can spot LNG make a profit in this market? To make a profit selling into the pipeline system at the Shanghai citygate plus the 20% winter price uplift, the landed LNG import price needs to be below $8.0/MMBtu. In a warm winter with domestic LNG prices dropping from the current level back to 5,000 yuan per metric ton, as in the 2019/20 winter, the landed price of LNG imports needs to be less than $12.5/MMBtu to make a profit in China's liquid market. A moderate winter scenario could mean China's domestic LNG prices remain at the current 6,000 yuan per metric ton level. In this case, the break-even price of LNG imports becomes $15.2/MMBtu. A winter supply shortage scenario would entail prices spiking up, as seen in the 2017/18 and 2020/21 winters. Such a price spike increases the break-even price of LNG imports to $17.9/MMBtu and $26.0/MMBtu, respectively, for domestic LNG prices of 7,000 yuan per metric ton and 10,000 yuan per metric ton, respectively.

But the higher the price, the higher the risk of government scrutiny owing to the consideration of price stability and the impact on market sentiment. Also, the domestic LNG market is highly sensitive to price. Since the end of July 2021, certain industrial gas end users such as ceramics and glass factories have reportedly curtailed production owing to high fuel costs.

Although high-priced domestic LNG market in the upcoming winter bodes well for LNG imports' profitability, the liquid market's size and profit margins will depend on how Chinese demand responds to winter weather. Like in many past winters, supply curtailment will be the tool that Chinese gas suppliers resort to in a cold winter event instead of paying for highly priced spot cargoes.

Learn more about our Asia Pacific energy research and insight.

Jenny Yang is a Senior Director covering Greater China's gas and LNG analysis.

Megan Jenkins is a Senior Analyst covering Greater China's gas and LNG analysis.

Posted by 10 September 2021

This article was published by S&P Global Commodity Insights and not by S&P Global Ratings, which is a separately managed division of S&P Global.