Beyond soybeans: The ripple effect of US-China trade tariffs on agribusiness

Soybeans have taken center stage in the ongoing US-China trade war, ever since China's Ministry of Commerce imposed a 25% tariff on hundreds of US products in April 2018. As the dispute between the two countries continues, the knock-on effects of restricting trade of the largest US agricultural export have rippled out into the global agribusiness industry.

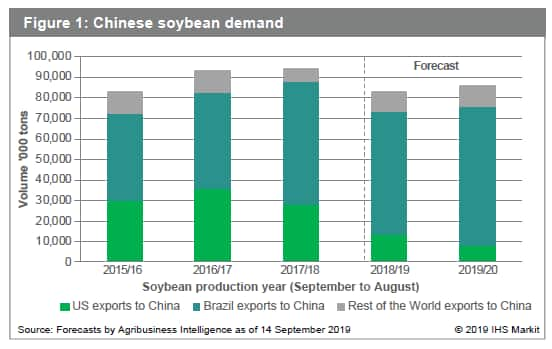

Soybeans are central to the US export picture. As the largest importer of soybeans, China is the largest soybean trade partner for the US, with shipments between the two countries topping 36 million tons in the 2016-2017 soybean crop year. As the full effect of tariffs takes hold, Agribusiness Intelligence forecasts that US soybean exports to China will slump to just 13 million tons for the 2018-2019 period.

While US exports to Europe and other markets have increased, the scale of demand simply cannot match that of China. The net effect is that US soybean exports are forecast to fall 20% in the 2018-2019 period.

The US government has made it clear that it is not going to forget its farmers. It will continue to provide aid to agricultural associations and their members. However, most farmers would prefer to get their returns from the market, a prospect that looks to be some ways off.

If an agreement is reached between the US and China soon, it would provide significant support for financial markets and the economy. However, an immediate translation into increased US agricultural exports could take longer due to structural changes in the international market.

China has taken steps to broaden its supply chain, making it unlikely that export volumes would return to pre-trade war levels. Other countries that developed supply agreements with China in the last 12 to 18 months are not going to give up newly gained market share without a fight.

Brazil is best positioned to fill the gap for a range of agricultural products. Agribusiness Intelligence estimates that Brazil's soybean exports to China have increased 36% in two years, totalling 63 million tons in the 2018-2019 period.

A prolonged trade war is likely to create a sustained impact on the US agricultural industry. Not only has the dispute impacted planting decisions by US farmers - who are focusing more on wheat, corn, and other crops - but it has affected other US agricultural companies. With financial uncertainty on the horizon, many farmers have been holding back on investment in new machinery and other inputs into their businesses such as technology.

Other adjacent industries such as fertilizers, crop protection chemicals, and biofuels are also impacted. Let's look at how trade is changing.

Fertilizers

The trade war is not directly impacting the fertilizer market, as both the US and China are mass exporters and make the most of their fertilizer production. Indirectly, though, the change in crop planting by US farmers has a knock-on effect to the domestic fertilizer industry. As tariffs on soybean exports to China have forced farmers to rethink planting patterns, the changing mix of crops impacts the nutrients required. As a legume, soybeans absorb nitrogen from the atmosphere and do not require additional nitrates. However, like most agricultural crops, soybean yield is significantly improved with phosphates and potash.

The reduction in soybean planting has led to oversupply in the domestic fertilizer market. However, with Brazilian farmers stepping in to fill the gap in China's soybean imports, US phosphate and potash producers have increased exports to Brazil. Compared with Atlantic market rivals Russia and Morocco, the US is better-positioned to serve the South American market, due to reduced shipping costs.

Crop Science

Developments in the US and China were already affecting the global crop-protection market long before the tariff war began. Ongoing US legal cases for glyphosate, the largest-selling herbicide in the world, as well as some other herbicides, cast doubts about the potential of these active ingredients for manufacturers internationally - not just in the US. Furthermore, the global market's reliance on the Chinese manufacturing sector for agrochemical products left it vulnerable to developments within China. Stricter environmental laws within China drove many smaller companies out of the market, which in turn increased international product prices.

Then the trade war began exerting an influence. China is the manufacturing hub for the global pesticide industry, accounting for around 25% of all production. The 10% tariffs implemented in 2018 mainly impacted formulated products being imported into China, leaving imports of most of the large-selling actives such as glyphosate and chlorpyrifos out of the tariff net. But the latest round of tariffs includes some of those active ingredients as well. With these tariffs, most US companies would have to pass the increased costs on to farmers, which in turn would impact sales.

Additionally, as China's demand for US soybeans disappears, many US farmers have adjusted their crop plantings. This in turn has changed chemical requirements and demand for particular products.

If the trade-war was resolved and trade reopened in the next year or two, the supply-demand balance could likely return to normal. If the conflict continues for an extended period, it could change the structure of the market entirely.

Animal Health

While tariffs have not hurt the vaccination or pharmaceutical markets of the US and China, the indirect impact on this market is already apparent. Animal health companies in China almost exclusively serve the domestic market, with animal vaccines produced to protect the Chinese livestock population. Although not regarded as being as high in quality compared to international products, Chinese products are significantly cheaper for small farms to buy. The exception is farmers' purchases of vaccines for fast-spreading diseases that could quickly wipe out an animal population. For example, Chinese pig farmers are increasingly purchasing doses of foot-and-mouth disease vaccines from international businesses.

This trend ties into the wider soybean-led trade war. Agribusiness Intelligence estimates that since its initial outbreak in China in August 2019, African swine fever (ASF) has decimated around 30% of the Chinese hog population. It also has spread to several other countries. As soybeans make up the largest proportion of hog feed, there is notably less demand for soybeans from Chinese farmers. There is no available ASF vaccine and the launch of such a product estimated to be five to seven years away. Thus, the contribution of the country's hog population to soy demand will not support pre-trade war import volumes, even if the trade war concludes.

Biofuels

The US ethanol industry has reached the climax of a crisis that had been building over the last two years. Political decisions were made to support the oil industry even when reduction in demand from China was already hurting US producers.

In August 2019, the US Environmental Protection Agency granted 31 exemptions to small oil refiners. The waivers free them from an obligation - under the country's renewable fuel standard policy - to blend biofuels such as ethanol into the gasoline they produce. The latest round of exemptions brings the total to 85 since President Trump took office in 2017. Earlier waivers already led to significantly reduced demand for ethanol, creating a disastrous psychological effect on the US ethanol industry. In fact, several players have said they will shut down or reduce production at their facilities.

Up to 40% of US corn is used for ethanol production, and many farmers that planted both corn and soybeans had increased their volumes of corn after the 2018 tariffs were imposed on US soybean exports to China. The increase in corn production exacerbated the issues of the ethanol industry - introducing more goods to an export market hit by reduced demand just as the trade war halted exports to China.

In 2017 the Chinese government announced plans to roll out nationwide use of car fuel containing 10% ethanol by 2020, in a bid to reduce pollution and smog in urban areas. Although ethanol can be produced domestically, the build-out of production capacity has not been fast enough to meet the deadline.

With the US offering the cheapest source of ethanol internationally, early 2018 saw record US exports of ethanol to China. Before the tariffs, full-year 2018 exports would have totalled over 500 million liters.

If the trade war came to an end and the export market reopened, Chinese demand for US ethanol could increase by 1 billion to 2 billion liters a year. This would in turn help to rebalance the US supply-demand issue. Only time will tell whether the key players decide this is in their best interests.