EU caps power trading revenues – but what is the impact?

Europe's energy crisis has been in the headlines for most of 2022. Owing to the gas supply crisis, worsened by low nuclear availability, European power users face exceptionally high power bills this winter. The affordability issue is top of the agenda for most governments. Among the measures being rolled out by the European Commission to soften the impact of high prices is an emergency regulation in the form of an inframarginal price cap on all the market arrangements (trades) in the wholesale electricity market. The new measure aims to reduce the impact that the price-setting marginal power plant— typically a gas-fired generator — has on the revenues of low-marginal cost generators - which are usually renewables and nuclear.

Since the liberalization of power markets in Europe, wholesale power prices have been set based on the variable cost (principally the fuel cost and emissions cost) of the most expensive power generator that is required by the power system in order to cover demand - this generator is also called "the marginal", or "market clearing" generator. In turn, power generators that have a lower marginal cost than the "marginal" generator benefit from an "inframarginal" rent. With the decline in coal and oil capacity, and because nuclear and renewable assets largely have low variable costs, gas-fired assets have become the "marginal" technology in Europe most of the time. So, in theory, the consequence of this model is that in recent months renewable power plants have been benefitting from fuel costs driving up the power price.

What does the cap on inframarginal plants mean? The aim of the intervention is to limit the revenues that renewable and nuclear power plants earn compared with their costs. This might sound counterintuitive - Europe wants more renewables - but this decision is motivated by the fact that excess revenues will be allocated to help finance national level efforts to lower final user bills.

The proposed cap is €180/MWh, although member states will be able to decide on their own cap above this benchmark, and allow exemptions if necessary. The measure will impact both those plants which are currently making revenues in the day-ahead market when the price clears above €180 EUR/MWh, and those that hedged their position in advance via forward contracts at a price higher than the proposed cap itself. Therefore, the mechanism could have a country-specific impact, varying according to capacity structure and organized market.

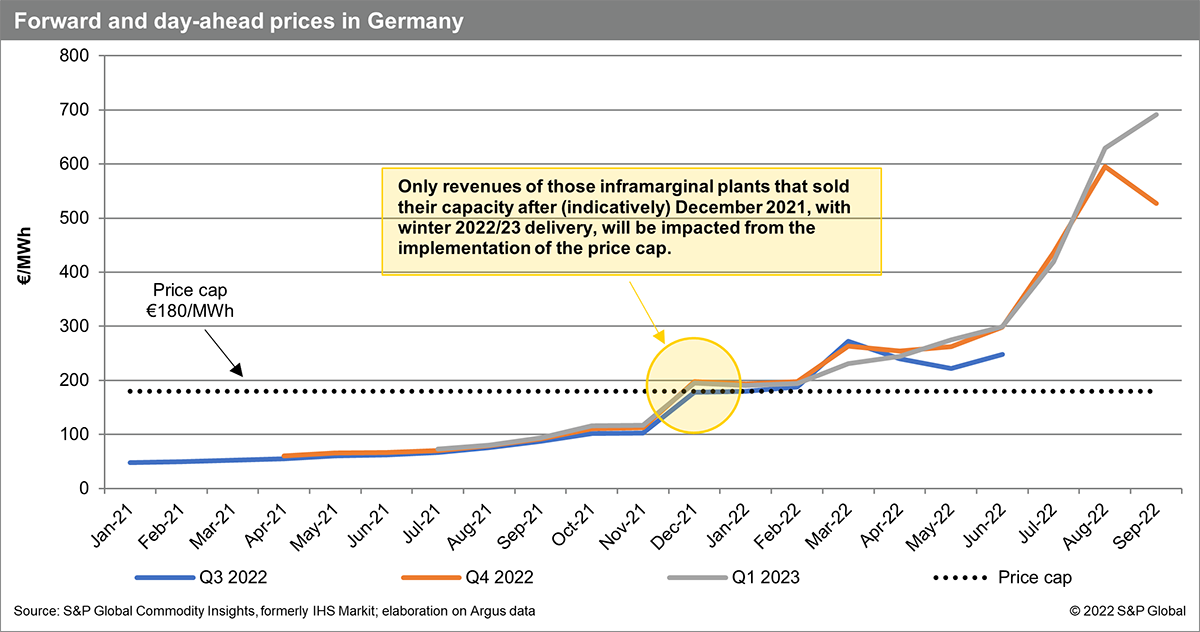

In fact, in the European power market, it is a well-established practice for operators to sell a share of their planned production in advance, through forward contracts or Power Purchase Agreements. So, for example, let's say a producer had sold 50% of their anticipated production back in 2021 on a forward price curve for delivery in Q3 2022. If that price contract traded below €180/MWh, there would be no impact on revenues from the new price cap. Renewables that benefit from government support schemes usually fall into this category, as they have a long-term purchase contract at a pre-determined price. The chart uses Germany as an indicative example of the impact:

In practice, only a fraction of the revenues of inframarginal assets will be impacted by the imposition of a price cap, because only a part of the capacity is benefitting from the current high-price environment. Consequently, the impact of the measure will be impactful for those assets selling their output in the day-ahead market, but it will have weaker consequences for those plants that sold their capacity when forward prices were below the cap.

Learn more about our research into European energy.

Zoe Grainge, senior analyst with the Gas, Power, and Climate Solutions team at S&P Global Commodity Insights, focuses on the fundamentals of the European gas market.

Giovanni Giansiracusa, senior research analyst with the Gas, Power, and Climate Solutions at S&P Global Commodity Insights, currently focuses on European power sector modeling.

Posted by 16 November 2022

This article was published by S&P Global Commodity Insights and not by S&P Global Ratings, which is a separately managed division of S&P Global.