Will lingering controversies overshadow Nigeria’s Petroleum Industry Bill progress?

On 15 July, the Nigerian National Assembly (NASS) passed a final, unified version of the Petroleum Industry Bill, 2020 (PIB), which harmonised differences between the initial versions of the bill passed by the legislature's two chambers, the House of Representatives and Senate, at the beginning of the month.

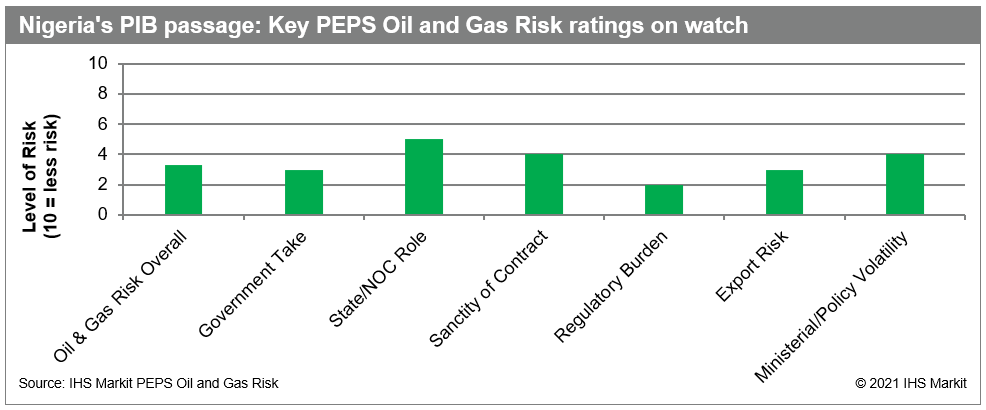

If enacted, the PIB will revamp most of the country's hydrocarbon regulations and institutions, and set its oil and gas investment terms for at least the next decade, shaping above-ground risks for E&P investors (see chart below). If President Muhammadu Buhari assents to the bill without raising any objections, the PIB will become law shortly after. If Buhari does object, the bill will be sent back to the NASS, which can either revise the objectionable sections to obtain the president's approval or override the objections via a two-thirds majority vote, in which case the PIB would be automatically enacted as is.

Industry stakeholders appear to have set aside their

differences so that reform can finally happen

The PIB's passage demonstrates a political consensus that oil and gas legal reform can no longer be put off after several failed attempts dating back to the late 2000s. Reaching this point has involved a great deal of strain: two oil price crashes; several bouts of large-scale pipeline sabotage; two recessions; a pandemic; rising insecurity; dwindling upstream investment; mounting government indebtedness; and a growing recognition of the global energy transition - and the potentially devastating impact that this could have on the hydrocarbon-dependent state.

As a result, resistance to the bill has softened. Various petroleum-sector interest groups and ethno-regional political blocs previously refused to compromise or make concessions for fear of giving up existing or potential rents or benefits. This prevented past versions of the PIB from being passed. Although such points of contention still exist, they may not be the deal killers they once were, mainly because the cost of delaying reform further appears to be growing unacceptably high for most - if not all - of the key stakeholders, including the national government, investors, sub-national governments, hydrocarbon host communities, and labour unions.

Nevertheless, controversies still exist, threatening the reform effort and impact

One element of the PIB that remains contentious is the final contribution amount - a percentage of licence holders' annual operating expenditures - to be set aside for proposed host community development trust funds. The government originally set this at 2.5% but the Senate raised it to 3% while the House hiked it to 5% in response to pressure from Niger Delta groups seeking 10%. However, the harmonised version set it at 3%.

Officials in the Buhari administration have said that an upward

revision risks putting off E&P investors, particularly foreign

firms that can readily invest elsewhere. International oil

companies (IOCs) have criticised the trust funds, arguing that such

funds would introduce additional costs and complexity that would

reduce Nigeria's upstream attractiveness and constrain new

investment.

Although the funds are unlikely to be scrapped, a final

contribution amount of 2.5-3% could stoke resentment in the

oil-producing region and potentially provoke a new wave of pipeline

vandalism there. Indeed, the Niger Delta Avengers militant group

has threatened to attack oil and gas infrastructure if the PIB or

resulting law is deemed insufficiently favourable to the region. In

2016, the Avengers sabotaged several important pipelines, which cut

the country's petroleum production by several hundred thousand

barrels per day and depressed output for several months.

Other politically charged issues such as a proposal that the reformed national oil company (NOC) allocate 30% of its profits to funding exploration in frontier basins, which are primarily located in northern Nigeria, could yet complicate the conclusion of the legislative process. This provision is viewed by many as an inducement to mobilise support for the bill from politicians from the north. However, it would seemingly cut against the PIB's efforts to make the NOC more profitable, more self-reliant, and less politicised, particularly since there is no shortage of E&P investment opportunities within the Niger Delta basin. Notwithstanding the potential pitfalls, there is still a good chance that the bill will be enacted soon and with relatively few changes given the urgency for reform.

E&P impact uncertain despite concessions made to investors

That said, the likely investment impact of the passed PIB remains unclear. This is because the substance and extent of the investor-friendly revisions that were made in March or April to the harmonised bill - ostensibly focused on fiscal terms - have yet to be disclosed. IHS Markit is reviewing and analysing the House of Representatives' report on the version of the bill it passed at the beginning of July. Fiscal changes are necessary to boost Nigeria's prospects of attracting new investment to raise its upstream production while also increasing domestic utilisation. The crucial question is whether these alterations will go far enough to incentivise investment (see our previous blog here). IOC representatives have reportedly been meeting with the government to discuss the passed bill. There may still be an opportunity to make some final tweaks, but the PIB could yet come up short for investors in key regards.

Nigeria's hydrocarbon output is highly dependent on the PIB sparking project development

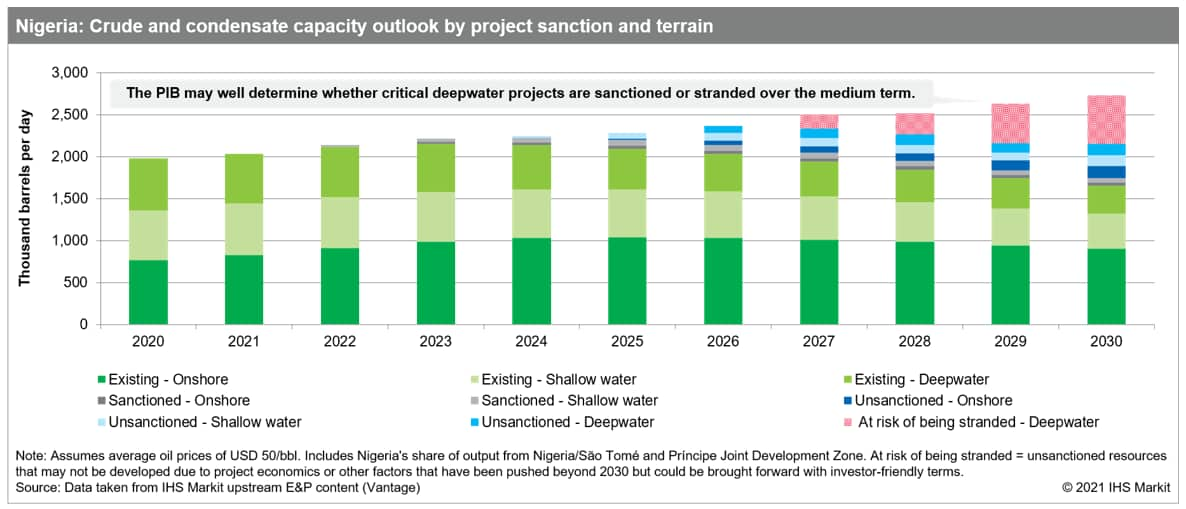

The trajectory of Nigeria's future oil and gas production largely hinges on the bill. IHS Markit cut the country's average forecasted output by around 300,000 barrels per day over the next three years due to projected global, industry-wide cuts related to the energy transition, and pushed out the start dates of several unsanctioned projects.

If the PIB is enacted and implemented quickly and is considered to be sufficiently favourable to investors, that could help with the sanctioning and advancement of some relatively large new Nigerian upstream developments. An area of particular focus for the country should be the unsanctioned deepwater projects, which could become stranded if the terms available are not acceptable to licence holders (as illustrated in the chart below). However, the May 2021 renegotiation of the Bonga South West PSC terms demonstrated that if the government and IOCs are able to find common ground on such projects, this could raise Nigeria's production outlook towards the end of the decade, which would also likely help to secure the country's output over the longer term.

Screen upstream opportunities and above-ground risk with PEPS from IHS Markit.

Visualise and understand each step of the oil and gas valuation process with Vantage from IHS Markit.

This article was published by S&P Global Commodity Insights and not by S&P Global Ratings, which is a separately managed division of S&P Global.