Why are natural gas prices going up and can the oil sector offer a relief valve?

Although the Northern Hemisphere's winter has yet to begin, natural gas spot prices around the world have absolutely skyrocketed over the past few months. The price of European benchmark Title Transfer Facility (TTF) has moved from less than $9/MMbtu in May to over $33/MMbtu last week. Asian benchmark Platts JKMTM (Japan Korea Maker), meanwhile, surged from less than $7/MMbtu in May to more than $34/MMbtu. Both natural gas prices have only continued in rise since then, with front month pricing for JKM surpassing $42/MMbtu and November futures for TTF reaching $40/MMbtu as of 5 October. (To put these numbers in context for more "oil-centric" readers, the current TTF gas price works out to around $230/b on an oil equivalent basis, with the JKM gas price equivalent to more than $240/b. The price of Brent, meanwhile, is today around $81/b.)

What has caused this still-ongoing surge in natural gas prices?

As with most commodity price surges, it is ultimately an issue of supply and demand. After a brief dip in 2020, global gas demand has effectively already fully recovered this year. This demand growth is partly just the continuation of trends that had been underway for decades before the pandemic. But it also reflects the confluence of several other more ad hoc factors. For example, prolonged drought conditions in Brazil have obliged that country to shift from hydro to natural gas for power generation. At the same time, the global coal market is facing significant supply side constraints, causing prices for that commodity to rise sharply. This, in turn, translates to more natural gas demand since the two commodities are often interchangeable in the power sector. Meanwhile, European natural gas stocks are extremely low thanks to an atypically severe 2020-21 winter, which necessitates atypical stock building ahead of the imminent 2021-22 winter.

On the supply side, several key LNG suppliers are suffering from reduced output, including Egypt, Norway, Trinidad, Peru, Nigeria and Angola—to name just some of the major contributors. In Europe, supply has been impacted both indirectly—by LNG being drawn away by growing demand in other global markets—and more directly by a major year-on-year drop in the United Kingdom (UK) production as maintenance overran during early summer.

The ongoing high price environment for natural gas is not occurring in a vacuum; it is also impacting the oil value chain. As noted, oil prices—and thus refined product prices—are currently far lower than are those for natural gas. This is incentivizing consumers of natural gas to switch to oil alternatives where the option still exists. Most notably, this means power plants switching from natural gas (or LNG) to oil derivatives—principally fuel oil but also potentially some gasoil and naphtha. That said, IHS Markit believes that such swapping will occur primarily in Asian markets. In Europe or North America, environmental considerations will limit power plants swapping out natural gas for oil derivatives.

Another potential avenue for gas-to-oil switching is within refineries themselves. Typically—and increasingly—refineries utilize natural gas as a fuel source. But refineries also have the ability to utilize LPG in lieu of natural gas. As with fuel oil in the power sector, IHS Markit believes such swapping is most feasible in Asia. Smaller volumes of switching are also possible in Europe and the Americas.

A final avenue for gas-to-oil switching is from the transportation sector. This includes both road transport and marine-going vessels. However, the overall scope for such swapping is deemed to be relatively limited. Few marine vessels have the optionality to run either LNG or fuel oil.

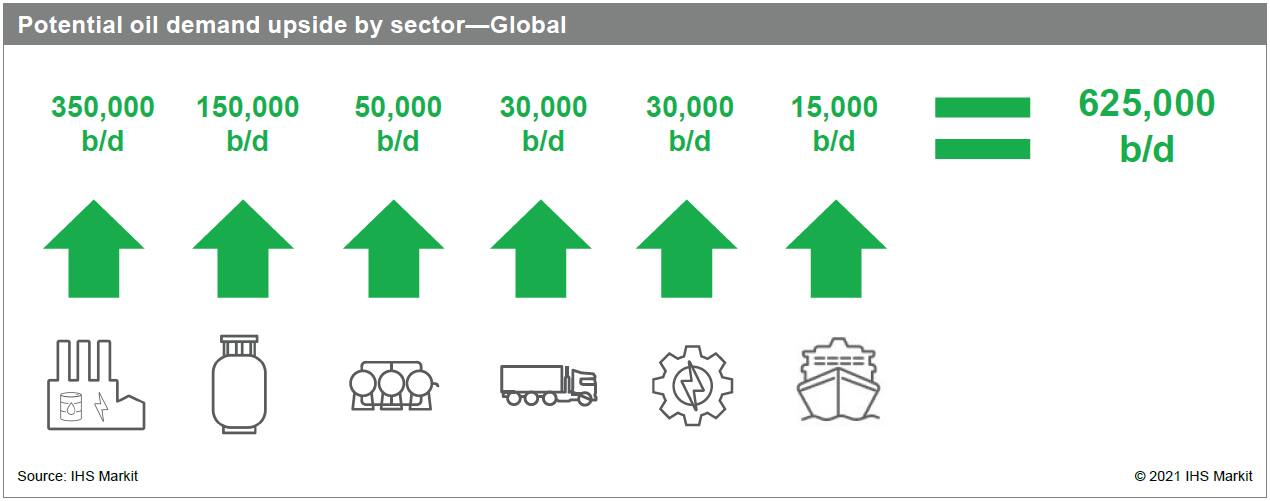

Overall, when all possible avenues of gas-to-oil switching are considered, IHS Markit believes there is around 625,000 b/d of potential "upside" to oil demand this winter. Around half of that would be incremental fuel oil demand from the power generation sector, with most of the remainder being additional LPG demand from the refining and petrochemical sector. Very limited incremental volumes of naphtha and gasoil could be utilized as well. For all products, most of the anticipated swapping would occur within Asian markets.

Is this demand upside enough to move the needle within oil markets? Perhaps. The oil sector is already beset by concerns about a looming supply crunch. Indeed, oil prices have trended upward over the past six weeks, with a particularly strong increase occurring since mid-September. The incremental oil demand volume that could arise from natural gas swapping is still a drop in the bucket of overall world oil demand. And it should be emphasized that this estimate is in many ways the maximum potential volume that could be swapped. But the global crude balance is tighter than many realize, and market anxiety is high at the moment. Faster-than-expected crude stock drawdowns this winter could easily send prices up into the $90/b range.

The bigger implication of this analysis is that there are very few "relief valves" for the ongoing natural gas price surge. It is simply not very feasible for consumers of natural gas to swiftly pivot to alternative fuels in sufficient quantity to blunt the supply crunch. Indeed, this is exactly why natural gas prices have separated so dramatically from oil prices over the past month.

Oddly enough, the state of play for global energy markets—particularly natural gas markets—this winter will truly depend on the weather. A relatively mild winter will ease tightness in both oil and gas markets, while a particularly frigid winter will send both oil and gas prices soaring even higher than they already are.

Learn more about Oil Markets, Midstream, and Downstream services from IHS Markit.

This article was published by S&P Global Commodity Insights and not by S&P Global Ratings, which is a separately managed division of S&P Global.