Top issues for oil markets and mobility in 2021 after a tumultuous year

2020 was a tumultuous year for oil markets, and energy markets more generally. The COVID-19 pandemic decimated global oil demand, which plummeted in the second quarter at an astonishing rate as lockdowns and other pandemic-related restrictions came into force and whole countries abruptly stopped driving and flying. Oil prices tumbled, and a brief price war between Saudi Arabia and Russia deepened the rout until an historic agreement was struck between OPEC and several non-OPEC producers to slash output by the greatest volume in history—nearly 10 MMb/d. Other producers outside the agreement joined the cuts, albeit involuntarily—with customers disappearing, and in some cases with nowhere to store the excess output, their only choice was to shut in wells. This great shut-in of production and some recovery in oil demand in the second half of the year helped prices partially recover.

What comes next? The precise contours of the post COVID-19 era for oil and energy markets have yet to emerge. But we can already anticipate what some of the key themes will be for this year—and potentially beyond.

Oil demand and the energy transition

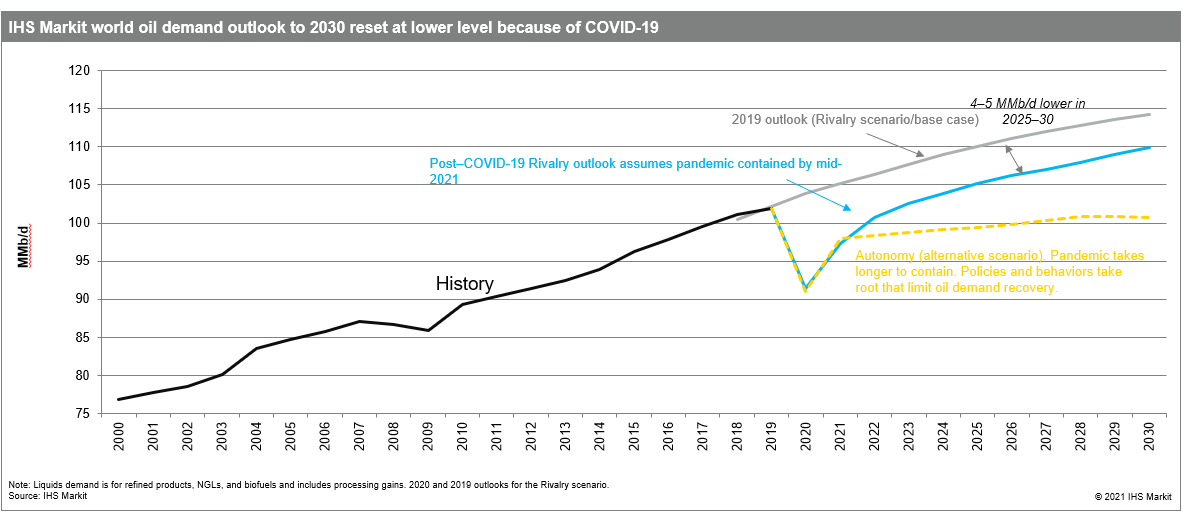

For the oil market, the biggest uncertainty is the future path of demand. Yes, vaccines are now being rolled out, and world oil demand will almost certainly jump later this year as the pandemic is contained, economic activity increases and travel rebounds. But there are reasons to believe that a return to the roughly 1% average annual increases in world oil demand that have occurred over the past three decades may not resume. In the IHS Markit Autonomy energy scenario—which depicts a faster transition to a lower-carbon economy than in our base case Rivalry—2019 is the highwater mark for world oil demand, owing to the emergence of new consumer behavioral trends and government policies that limit oil consumption. An early peak in world oil demand would have profound implications for energy industry strategy, investment and oil prices. Upstream oil companies will be considering investment decisions with this potential peak in mind.

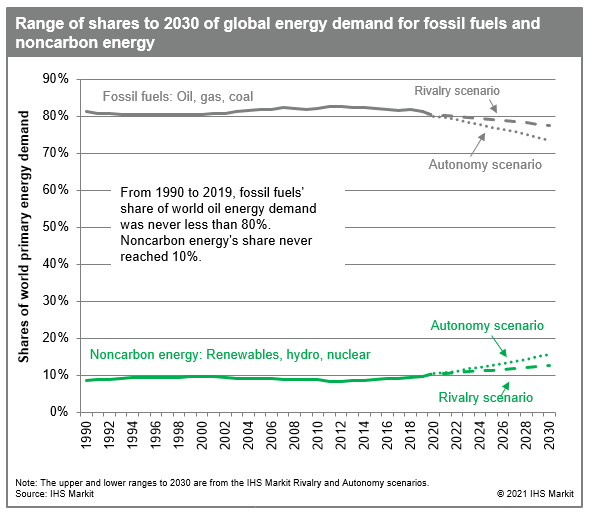

2020 was also the year when the energy transition appears to have reached a pivot point. From 1990 to 2019, decarbonization has been moving in slow motion, with fossil fuels maintaining about an 80% market share of world primary energy consumption. But the pandemic reduced fossil fuel usage by a record amount.

There was also a marked shift in investment away from oil and gas and to renewables, driven by several trends. First, costs for renewables like solar, wind and batteries continue to drop, pointing to further gains in noncarbon energy's global market share over the next decade. Second, environmental, social and corporate governance (ESG) criteria are becoming increasingly important for investors. The COVID pandemic has also prompted some big oil companies, such as Shell and BP, to accelerate their energy transition strategies, shifting investment away from traditional oil and gas activities. Finally, governments around the world are setting ambitious "net zero" targets for their economies. Can the energy transition finally move beyond slow motion in 2021?

The oil supply challenge

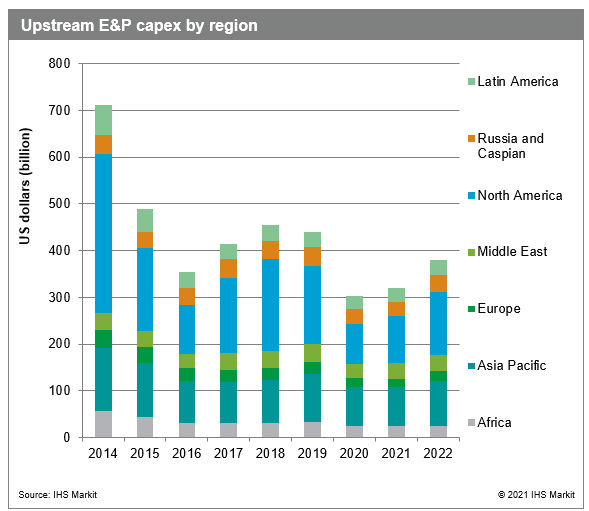

Even if the future oil demand growth profile is flatter, upstream investment is still needed—after all, existing production is constantly in decline, requiring new sources of supply to backfill it. In fact, it is plausible that insufficient investment in the years ahead could eventually result in a much tighter market and oil price spikes.

Global E&P capital spending fell 30% in 2020, with the biggest drop in North America. Even with a recovery in oil prices and revenue, the industry faces a unique set of challenges that could constrain future investment. Oil company debt levels are at record levels, and its investors are disenchanted with the sector. Over the past decade, the energy was the worst-performing sector in the S&P 500 index, and investors are clamoring for higher returns. Oil companies, especially the US shale sector, are heeding that demand, and capital discipline is the watchword for the foreseeable future. An added headwind is that the cost to develop new upstream projects is not expected to decline much.

The oil market's heavyweights in OPEC (and their non-OPEC partners—especially Russia) also face a supply challenge—how to calibrate the return of their barrels to the market as demand recovers from the pandemic. This effort will be fraught, since the group is internally divided over its strategy. For example, Russia favors increasing supply at $50/bbl, unwilling to forgo market share. Saudi Arabia, however, prefers higher prices. Meanwhile, higher output from Iraq and potentially from Iran could further test the unity of the group.

The Biden Administration's policy ambitions will leave a mark on the energy and automotive industries

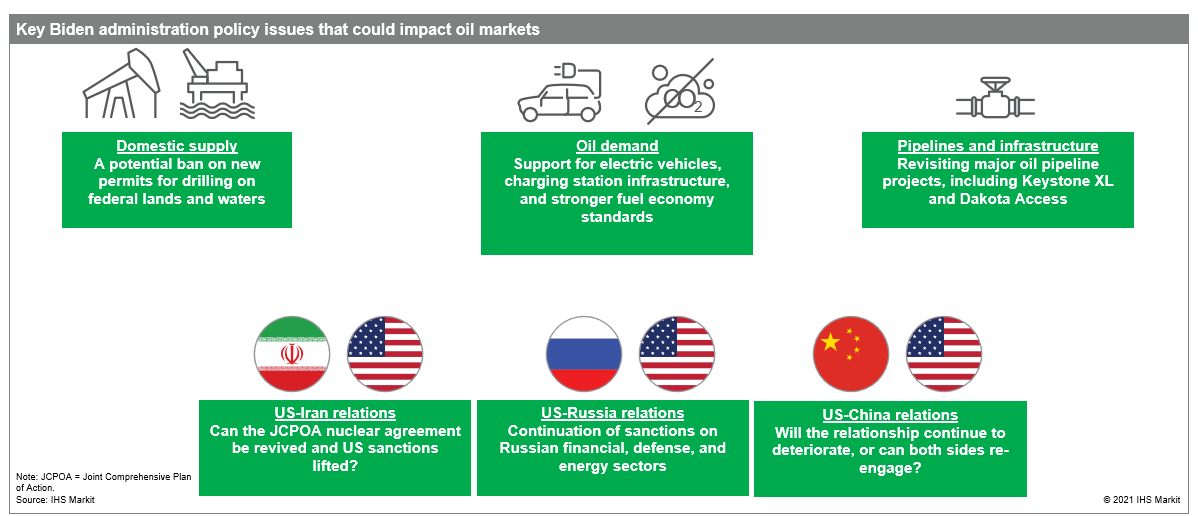

The change in US government leadership will also have important repercussions for the oil and gas industry. For example, the Biden Administration has proposed a ban on new permits for oil and gas drilling on Federal lands and waters. Most drilling is on private land, but if the ban is implemented, it could still eventually suppress the long-term potential output of US oil production. On 20 January—Biden's first day in office—he revoked the cross-border permit for the Keystone XL pipeline, and work on the project has since been suspended.

Relationships with key allies and geopolitical adversaries could also shift with a new US administration. Perhaps most importantly for the oil market, the Biden Administration is seeking to revive the Iranian nuclear agreement (the "Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action"). If Trump-era US sanctions on Iran are eventually lifted, the country's oil production and exports could rise very rapidly, challenging the efforts of OPEC+ to manage global supply. Evolving US relations with China, Russia, and Saudi Arabia could also buffer oil markets in unpredictable ways.

The Biden Administration is also supporting policies aimed at reducing GHG emissions from the transportation sector, which remains heavily reliant on petroleum, and is the primary source of oil demand in the United States. President Biden will likely move to accelerate increases in US fuel economy standards for passenger cars and light trucks and promote electric vehicles (EVs). Pro-EV policies pursued by Biden may include supporting the construction of more charging stations, a push to buy "clean" vehicles for public sector fleets, and more generous consumer EV purchase incentives.

More broadly, in 2021 and beyond, the transportation sector is likely to come into greater focus among policymakers around the world seeking to put their economies on a path to net-zero emissions. In 2020, the United Kingdom, California, Massachusetts, and Quebec separately set 100% zero emission vehicle (ZEV) new sales goals in the 2030-35 period. More such targets are likely in the offing. However, governments will also need to put in place tougher regulations—including tighter fuel economy/GHG emissions standards—that constitute the "blocking and tackling" needed to realize such ambitions.

While ZEVs will continue to be a policy-driven market for years to come, there are other factors that will help determine the pace of ZEV adoption as well—including a narrowing difference in the price of battery electric vehicles and internal combustion engine vehicles; increased availability of EV chargers outside the home; and the availability of many more ZEV models, including sport utility vehicles.

Click here for more insight and analysis on Crude Oil Markets from IHS Markit.

This article was published by S&P Global Commodity Insights and not by S&P Global Ratings, which is a separately managed division of S&P Global.