Unprecedented challenges in global crude supply impact E&P company futures

The future for global crude oil supply faces perhaps the widest array of challenges and uncertainty since the mid-1980s. Factors influencing the competitive supply of oil include: volume, quality, and cost of supply of remaining resources; investment behavior; and concerns about demand destruction or "peak oil" in a political environment focused on promoting renewable technologies.

The drive to short cycle-time, unconventional projects onshore in North America and elsewhere seemed irresistible for a large swath of publicly traded companies. This focus accelerated after the 2014 price drop albeit with a lag. The business proposition rested on dramatic performance improvements, lower risk (both actual and perceived), capital flexibility, and the transparency of activity. It was also true that a great deal of conventional activity was not making money prior to 2015, as upstream return on capital employed (ROCE) fell progressively from 2010, even with $100 oil prices.

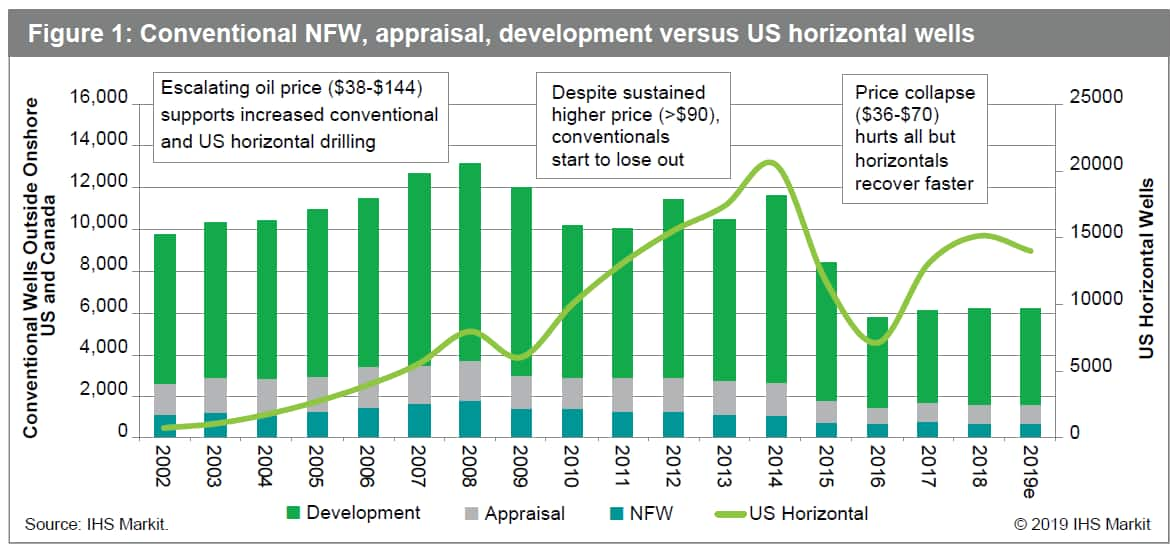

Still, the exploration and production (E&P) business is incredibly dynamic. Disenchantment with financial returns from unconventional production onshore in North America is now reducing investment there - even as larger operators determine different development pathways that emphasize financial returns but with lower growth. Investor questions may even drive more operators back to conventional exploration in the medium term, or conversely, drive investors out of the upstream sector altogether. Offshore companies have been able to substantially reduce the costs of building and operating the offshore facilities necessary to develop resources in deeper waters. Global conventional development drilling has picked up since 2015 but only slightly, remaining well short of pre-2016 activity levels (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Conventional NFW, appraisal, development versus US

horizontal wells

Offshore conventional new field wildcat (NFW) activity has experienced only incremental gains at best, which will create a knock-on effect on development drilling. From a global perspective, conventional exploration and discoveries are at the lowest level in seven decades. This is not due to lack of resource potential but rather to investment behavior, enforced by the financial sector.

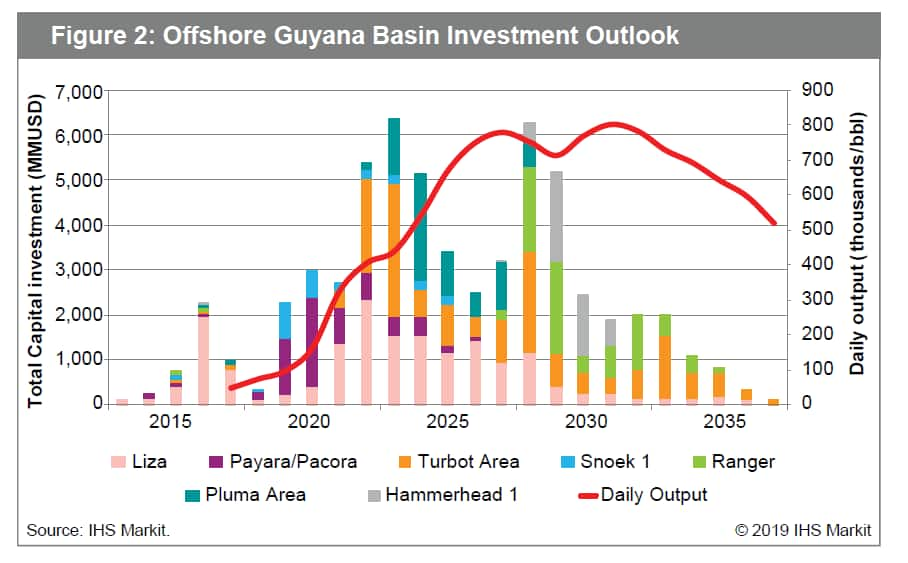

Some larger E&P companies and a few E&P independents continue to pursue selective deepwater exploration. For example, ExxonMobil and its partners, Hess and China National Offshore Oil Corporation, have been very successful in the western portion of the Guyana Basin (offshore Guyana). Over six billion barrels of oil-equivalent recoverable resources have been discovered in Guyana since 2015, with the first volumes coming onstream at the very end of 2019. Additional discoveries by Tullow Oil and its partners have been made in more shallow water, but commerciality has not yet been established. In an environment where operators are largely focused on becoming cash flow-positive as soon as possible and financing future development activity from within the existing cash flows, these assets in Guyana represent an ideal package (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Offshore Guyana Basin Investment Outlook

They offer globally competitive economics with break-even points for the confirmed projects averaging around US$41 per barrel (bbl), with a range between US$23/bbl and US$60/bbl. They also offer shorter project cycle times than have existed in typical deepwater developments, with the assets returning positive cashflows within the first two to four years of production.

In short, there are E&P companies with engaging, financially attractive portfolios, strategies, and performance to come. But how many Guyana Basins or Johan Sverdrup's (in offshore Norway) are there? There may be other new sizeable crude streams that are highly competitive, with break-evens at $25 to $45 per bbl. However, even if volumes are 300,000 to 500,000 bbls/ day, this does not make up for overall industry trends. There are simply not enough highly competitive investment opportunities for enough oil and gas companies.

National oil companies face additional intense pressures and obligations, but mostly it is a favored few (via natural endowments and high capabilities) versus the many. Overall, the industry remains more challenged than ever. Has the global competitive landscape in E&P really changed, or is it the fact that the financial sector has less patience with E&P against the backdrop of the energy transition?

Consider the concerns about demand destruction or "peak oil" in a political environment determined to promote renewable or green technologies. Current concerns over global warming and the resulting shift to renewables have led to some scenarios that show a peak in oil demand as early as the 2020's; other scenarios show oil demand peaking beyond 2030. Given this uncertainty, the industry appears to fear over-investment rather than under-investment. We see this in diminished conventional drilling; slowdowns in unconventional drilling; seismic acquisition; new acreage acquisition; and declining investment in improved oil recovery/enhanced oil recovery projects.

Given these factors, IHS Markit predicts that the most competitive barrels in the future will be those that offer the lowest cost, lowest emission, and shortest cycle time (that is, faster time from decision to cash flow), and flexibility of capital commitment. Arguably the best short-cycle conventional resources are in the Gulf countries as well as Western Russia. Others include selected shallow water areas globally; subsea tiebacks in maturing phase deepwater basins (where infrastructure rules); and best-in-class new deepwater plays, whether in the Guyana Basin or certain deepwater basins in Brazil. Other resource classes include much lower but more profitable growth in onshore North America and big, albeit long-term natural gas plays. These opportunities and the required performance are not available to all or even many companies, however.

Large basins can provide the scale and materiality to achieve further cost reductions via improved performance, infrastructure sharing, and fiscal regime change. But, smaller, higher-cost basins may struggle to attract investment in a low-crude oil demand scenario. Most governments will not easily accept declining investment in domestic basins due the impacts on revenues, employment, and national energy concerns. But how many governments have the capacity to sustain E&P investment in less-competitive basins for extended periods?

The E&P sector has more options than ever before from a subsurface perspective. Yet collectively it faces unprecedented challenges due to the uncertainties in future oil and gas demand and investor concerns. The industry is unquestionably resourceful. Since the oil price downturn in 2014, new approaches to project design, applications of digital and other technologies, efficiencies in the supply chain, and sharp focus on company portfolios have combined to significantly reduce costs and create "high quality" assets which can compete in the future, uncertain business environment. For conventional offshore projects as example, it is not uncommon to see break-even costs at some 60% of the level that would have been achieved in 2014. Those companies that continue to apply these approaches relentlessly will be in the best position to appeal to investor sentiment within the financial community. But, there may well be too few "quality," competitive investment opportunities for the E&P industry as a whole; parts of the industry will not able to attract investment capital. The competitive landscape in global E&P will see further, deeply significant changes. This future E&P industry will then be able to take advantage of the inevitable opportunities that will emerge as the global energy sector continues to evolve.

Jerry Kepes is head of the Strategy & Competition

Group, Upstream Research & Consulting Division at IHS

Energy.

Siddhartha Sen is a Director of Energy Research &

Analysis at IHS Markit.

Keith King is a senior advisor at IHS Markit.

Posted 12 February 2020.

This article was published by S&P Global Commodity Insights and not by S&P Global Ratings, which is a separately managed division of S&P Global.