US biofuels have been boosted by the RFS and RINs, but can a fresh approach drive new growth?

The Renewable Fuel Standard (RFS) has undeniably fallen far short in driving the type of greenhouse gas (GHG) emission reductions envisioned when the program was implemented in 2005 and expanded in 2007.

Congress had lofty aspirations for how much progress might be

made in the production of lower-carbon-emitting advanced biofuels,

but actual output has been meager. While the statutory volume

mandates were set at 21 billion gallons of non-corn ethanol

biofuels, including 16 billion gallons of cellulosic biofuel by

2022, cellulosic ethanol never saw the necessary technology

reakthroughs. To date, only about 36 million gallons have been

produced.

Renewable identification number (RIN) credits - the compliance mechanisms issued under the RFS that were intended to incentivize GHG-reducing technology in advanced biofuels - have become more of a political football than a driver of advancement in biofuels.

Corn-based ethanol provides a GHG emission reduction of around

40% from gasoline, according to a 2019 study from the US Department

of Agriculture. Biodiesel emissions are about 74% lower than

those

from petroleum diesel, according to lifecycle analysis from the US

Department of Energy's Argonne National Laboratory.

Those emission reductions are frequently touted by proponents of ethanol and biodiesel, but their effectiveness is often capped by blending constraints of 10% for ethanol and 5% to 20% for biodiesel in some states. Ethanol supporters have pushed to move to a nationwide E15 blend, but the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has only approved E15 for use in vehicles of model year 2001 and later and some states, including California, prohibit its sale.

A biofuel that doesn't have the same blending constraints and has identical properties to its hydrocarbon counterpart is renewable diesel, which has experienced a sharp growth in production and consumption in recent years. Renewable diesel can generate a variety of different RINs, depending on the method of production and delivery, but the RFS has practically been an afterthought in renewable diesel's rise.

Biofuel producers and refiners are jumping on the renewable diesel bandwagon, thanks in large part to incentives provided by the California Low Carbon Fuel Standard (LCFS), which sets annually lower targets for GHG emissions from transportation fuels. Fuels with carbon emissions above the target, mostly conventional gasoline and diesel, generate deficits, while fuels that can come in under the target - such as ethanol, biodiesel, and increasingly renewable diesel - generate credits. Like biodiesel, renewable diesel also collects a federal $1 per gallon blender's tax credit, which is in place through 2022.

LCFS credits have been a much more effective catalyst than RINs for driving improvements in the carbon intensity of biofuels.

While the RFS did fuel sharp growth for ethanol and biodiesel in the first decade of the program, policy decisions and market factors have flattened that trajectory in recent years. Because the RFS provides a guaranteed market for ethanol and biodiesel, the program is unlikely to lose its staunch political support in the Midwest.

But more states, including Washington, Colorado, and New York, are either considering or planning to adopt California-like programs, and there has been increasing talk of a nationwide LCFS program. While that's enticing to some in the biofuels industry, a looming concern is the growth in so-called zero-emission electric and fuel-cell vehicles and what they may mean for liquid fuels in the decades to come. There are currently no RINs pathways for zero-emission vehicles, despite calls for the EPA to approve them.

The rise of biofuels

When it comes to boosting US demand for biofuels, the RFS has

succeeded as a policy. Yet the program has reached a crossroads,

where proponents of low-carbon fuels are looking for more than

volume growth.

One of the key selling points when the RFS was approved was the ability to curb US dependence on foreign oil. The goal was to mandate increased use of biofuels, such as ethanol and biodiesel, that are made mostly in the agricultural Midwest.

After 15 years of sometimes dramatic twists and turns, the RFS has delivered mixed results. The program has turned into a seemingly unending tug-of-war between farm and oil lobbies, with near-constant litigation and recent efforts by the White House to keep both sides happy.

Opponents of the RFS - primarily refiners who have to generate or buy RINs to gain compliance - argue that it's a broken program that should be repealed or at least overhauled.

Renewable fuel backers counter that a properly run RFS can still meet the goals established by Congress. However, these proponents are becoming increasingly open to the possibility of augmenting the RFS with LCFS programs that are designed to drive greater reductions in GHG emissions from transportation fuels.

By nearly every metric, the RFS and RINs have provided substantial growth for ethanol and biodiesel, which have benefitted from congressionally established statutory annual biofuel blending volumes. The US consumed and produced about 4 billion gallons of ethanol in 2005, or less than 3% of total US gasoline demand that year, according to U.S. Energy Information Administration data. In 2020, ethanol capacity has more than quadrupled to over 17 billion gallons, and demand is expected to be just over 10% of gasoline demand. US biodiesel production has seen similar growth, exploding from less than 100 million gallons of production and consumption in 2005 to a likely 2 billion gallons or more this year. Refiners on the hook for RINs frequently complain about compliance costs. The RFS requires refiners and importers of gasoline and diesel to meet a percentage of their fossil fuel production, known as the Renewable Volume Obligation. Refiners who also have blending capacity at retail racks tend to collect RINs to offset their production of gasoline and diesel, but refiners who cannot blend have to buy RINs to satisfy their obligations. Studies conducted by the EPA and others, however, have suggested these costs are almost always passed onto consumers.

Policy turmoil

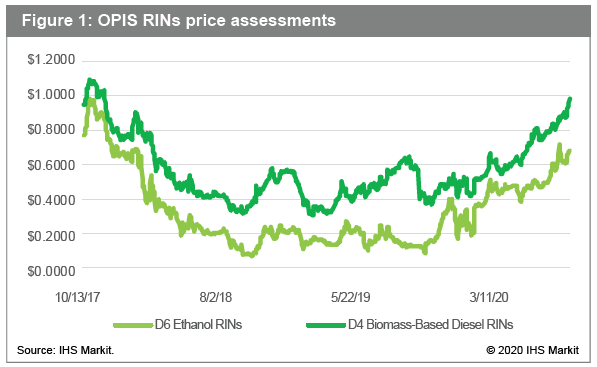

In recent years, policy turmoil around the RFS has led to extreme

volatility in RIN credit prices as refiners and speculators place

their bets on how difficult it may be for obligated parties to

achieve compliance. For the first few years of the program, RINs

generated from ethanol - categorized by the EPA as D6 credits -

were practically an afterthought, typically trading for less

than a nickel. In 2013, however, they briefly ballooned to

$1.50/credit on concerns that the so-called "blend wall" of 10%

ethanol blends could prevent refiners from being able to meet the

program's requirements.

RIN credit prices tumbled in early 2018 after the EPA dramatically increased grants of the small-refinery exemptions (SRE), leading to a surplus of RINs that were no longer needed by small refiners who were suddenly off the hook. The increased use of SREs by the Trump administration was a sharp shift in policy from the Obama administration.

The Obama White House's stingier approach to SREs was challenged in 2017 by Sinclair Refining, and the 10th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals found that the administration had exceeded its authority in denying SREs. But less than three years later in January 2020, the same 10th Circuit Court ruled that the Trump Administration's EPA had exceeded its authority in approving extensions of the SREs for three small refineries.

In the wake of that ruling, RIN credit prices quickly began to recover from their two-year slump and are expected to move even higher if the EPA applies the ruling - which affects only refiners within the 10th Circuit's jurisdiction - nationwide. Higher RIN credit prices tend to encourage higher blends of ethanol into the gasoline pool, as blenders and retailers are incentivized to discount the pump price of E15 or E85.

RINs are tradeable by any company with an EPA ID (and not just the biofuels producers who generate them and the refiners or importers who need them for compliance). As a result, RINs have been susceptible to speculation at times, with increased volatility fueled by buyers and sellers perhaps still haunted by the wild price run-up of 2013.

While the RFS has boosted demand for biofuels over the past 15 years, suppressed RIN prices have certainly not led to the technological advancement of next-generation biofuels that was originally intended. That shortcoming may lead to a new policy approach in the years to come.

OPIS Trade Link is an online full-day trading instrument for U.S. RIN and LCFS credits hosted on the OTC Direct trading platform. Trade Link allows market participants to submit bids, offers and execute deals for all credits needed to show compliance with the RFS, with no broker fees. Deals conducted on the platform will be given preeminent weight in formulating the OPIS benchmarked daily assessment range. This ensures the most accurate, transparent compliance credit pricing. Find out more and request free access: ihsmarkit.com/opis-trade-link

This article was published by S&P Global Commodity Insights and not by S&P Global Ratings, which is a separately managed division of S&P Global.