Customer Logins

Obtain the data you need to make the most informed decisions by accessing our extensive portfolio of information, analytics, and expertise. Sign in to the product or service center of your choice.

Customer Logins

BLOG

Nov 12, 2020

Shifting production from China: The Mexican option

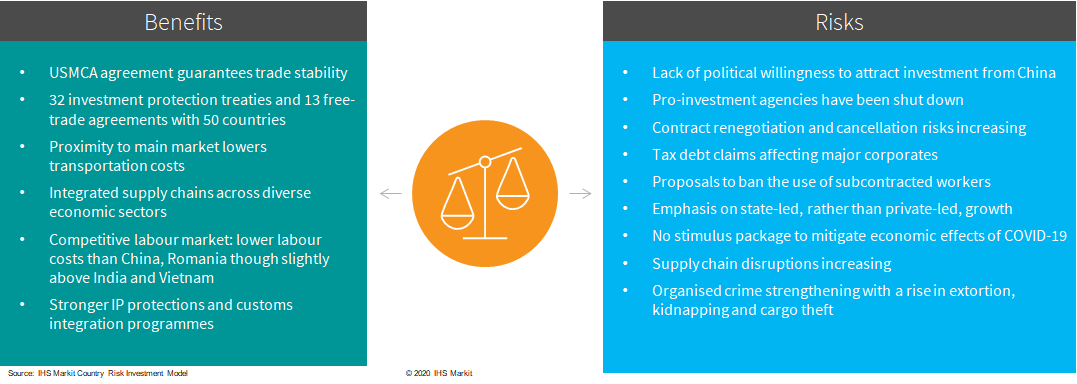

The 'decoupling' of the US and mainland China is compounding long-developing changes in relative wage rates around the world and forcing several companies to consider shifting their supply chains away from Asia. For those exporting to the US, neighbouring Mexico is an immediate option. It has established and easily leveraged supply chains with the US, which already accounts for over 80% of Mexico's exports; and strong industrial infrastructure, including productive hubs and extensive rail and road connections in the north and centre of the country, for example Chihuahua, Baja California and Tamaulipas (manufacturing) and Puebla and Guanajuato (automotive). In addition, the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), in effect since July 2020, has secured preferential trade terms with the US. Mexico also has free trade agreements with 48 other jurisdictions, including the European Union and the Pacific Alliance) and 32 investment protection treaties (including with Argentina and Brazil). Despite some rhetorical animosity between the US and Mexican governments, strong bilateral cooperation continues to improve trade logistics and security with, for example, the FAST and C-TPAT programmes.

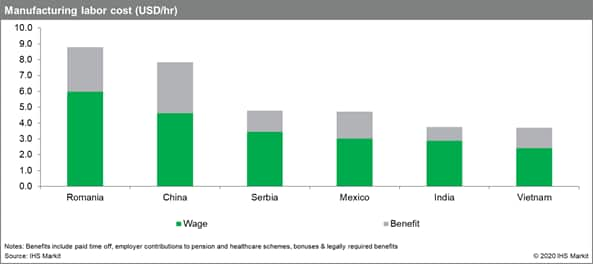

Comparative advantage

Labour also costs much less in Mexico than in China and Eastern Europe, and is comparable to parts of Southeast Asia. The average manufacturing wage in Mexico, including benefits, is around USD5 per hour, compared with USD8 in China. Its population is young and growing, with 73% under the age of 45, compared with 60% in China and 50% in Eastern Europe; and will be increasingly productive - upper secondary education became mandatory in 2012. Moreover, the improvement in productivity is likely to be greater in the industrial north and centre, areas that already have infrastructure advantages.

Political risks

The current political environment, however, complicates the argument. President López Obrador has not championed Mexico as an investment destination. His administration closed pro-investment agency ProMéxico, cancelled planned Special Economic Zones, and has strongly focused on domestic priorities and strengthening the state role in the economy. New entrants to Mexico, as well as existing investors, face significant risk of contract cancellation or renegotiation. Large projects across a range of sectors and states have been cancelled via public referendum, including the USD13bn Mexico City airport and a USD1.4bn brewery project in Baja California. Gas pipeline contracts were also renegotiated in 2019 with seven private companies due to "unfavourable" terms for the state. This increased legal uncertainty is likely to continue, with projects in the energy and infrastructure sectors or those with strong local and/or environmental opposition at highest risk of contract revision.

The current administration has also centralised business regulation. Regulatory agencies have been significantly weakened by budget cuts, with many likely to be consolidated into central government ministries. Such centralisation is likely to delay permits or even politicise which permits are prioritised. Large companies can also expect close scrutiny and increased auditing from Mexico's tax agency due to an aggressive drive to reclaim alleged historic tax debts. (IHS Markit's Sovereign Risk Service rates Mexico AAA on the generic scale in the one-year outlook but this deteriorates to BBB+ in the medium- term outlook.) The government is also seeking to ban the outsourcing of workers, currently a common practice in many sectors requiring temporary labour, due to claims that it costs the government USD1.1 billion per year in fiscal revenues. Any increase in revenues is unlikely to be used to support businesses through the economic effects of the Covid-19 pandemic. Partly due to this austere approach, IHS Markit forecasts a 9.9% contraction in GDP in 2020 followed by only a 4.3% rebound in 2021, compared with 1.9% growth and further 7.3% growth in China, for example.

Security risks

A more granular risk to supply chains in Mexico is disruption due to protests involving road and rail blockades. The number of rail blockades in 2020 has already doubled the 2019 figure, with the longest blockade taking place in Chihuahua from August-October causing reported losses of USD1.4 billion in lost trade plus additional transport costs, according to industrial chamber CONCAMIN. Protests are highly likely to intensify in 2021 as the unemployment rate rises - IHS Markit currently project 6.6% in 2021 - and the government perseveres with fiscal austerity. Indeed, this prompted increases in March in IHS Markit's risk scores for protests and riots (now 3.0/ High) and labour strikes (3.4/ Very high). In addition, organised criminal group activity including cargo theft and extortion will continue to affect business operations and exports to the US. Rail cargo theft hotspots include Sonora and Sinaloa in northern Mexico, typically targeting electronics, auto parts, chemicals and construction materials; while extortion demands and associated violent risks are likely to increase as criminal groups seek new revenue sources. Security risks dominate our country risk premium on Mexico over a 25-year horizon, based on our Country Risk Investment Model that is fed by those country risk scores. (Equivalent premia for China are much lower and dominated by regulatory risks.)

The Mexican option

We recently quantified two scenarios for the US and China's 'decoupling' and projected international economic and sectoral impacts to 2030: in both scenarios, Mexico emerges as a competitive alternative production location - in terms mainly of labour costs and infrastructure; particularly, of course, for US-oriented production. Including political and security risks, however, makes the proposition of shifting to Mexico far less straightforward. Careful engagement and a granular, site-specific assessment of potential, new ventures will be as critical as ever.

This summarises an event with Emily Crowley (Economics Associate

Director, Pricing and Purchasing), Rafael Amiel (Director, Latin

America and Caribbean Economics), Johanna Maris (Senior Analyst,

Latin America, Country Risk), and Alexia Ash (Associate Director,

Country Risk Consulting) on 21 October 2020.

Watch the event.

{"items" : [

{"name":"share","enabled":true,"desc":"<strong>Share</strong>","mobdesc":"Share","options":[ {"name":"facebook","url":"https://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=http%3a%2f%2fstage.www.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fshifting-production-from-china-the-mexican-option.html","enabled":true},{"name":"twitter","url":"https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?url=http%3a%2f%2fstage.www.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fshifting-production-from-china-the-mexican-option.html&text=Shifting+production+from+China%3a+The+Mexican+option+%7c+S%26P+Global+","enabled":true},{"name":"linkedin","url":"https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=http%3a%2f%2fstage.www.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fshifting-production-from-china-the-mexican-option.html","enabled":true},{"name":"email","url":"?subject=Shifting production from China: The Mexican option | S&P Global &body=http%3a%2f%2fstage.www.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fshifting-production-from-china-the-mexican-option.html","enabled":true},{"name":"whatsapp","url":"https://api.whatsapp.com/send?text=Shifting+production+from+China%3a+The+Mexican+option+%7c+S%26P+Global+ http%3a%2f%2fstage.www.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fshifting-production-from-china-the-mexican-option.html","enabled":true}]}, {"name":"rtt","enabled":true,"mobdesc":"Top"}

]}